France's elite confronted by sexual abuse scandals

- Published

Protest at Sciences Po Strasbourg: The slogans read: "We believe you" and "Silent institution = complicit institution"

Anna Toumazoff chose a powerful hashtag to highlight sexual abuse at France's top political science college. Sciences Po - the training ground for the country's presidents, politicians and administrators - became #SciencesPorcs (Science Pigs).

"This story is very French," Anna told me. "Because it's about great schools; it's about rape culture; it's about the elegance of being silent - that's very French."

Since then, the social media activist has received more than 400 messages from current and former students of Sciences Po. They describe sexual assaults and rapes, mostly by fellow students, that they say were not taken seriously by the college.

"Some were told that 'it's not the worst thing in the world', that life goes on," Anna said. "Others were accused of defamation. Some were considered liars. I haven't received any testimonies of people being well treated."

Stories like this are not new and not unique to Sciences Po. But she believes they are attracting wider attention now because the college is already under the spotlight for something else.

Breaking the incest taboo

France has been shaken by a series of incest allegations involving public figures over the past few weeks, beginning last month with the publication of a book by Camille Kouchner, in which she accused her stepfather, Olivier Duhamel, of abusing her twin brother as a child.

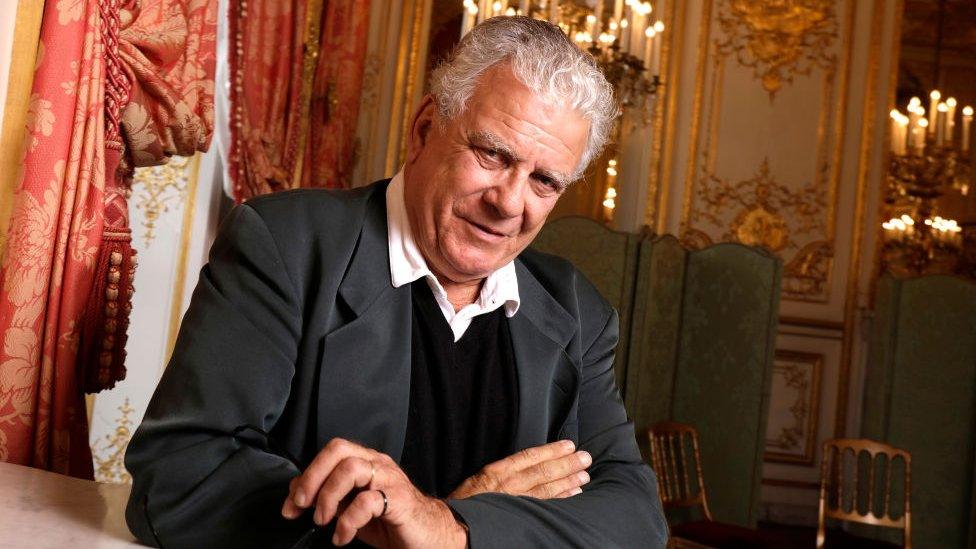

Olivier Duhamel resigned as head of a foundation overseeing Sciences Po

Olivier Duhamel, a political commentator, was the head of Sciences Po's Foundation. He resigned, along with the school's director who, it turned out, had also known about the allegations.

A government investigation into the college found no systematic cover-up, but noted that none of those who knew about the accusations had reported them, and said that the college should reinforce awareness of gender-based and sexual violence.

Sciences Po said in a statement that it "support[ed] the victims of gender-based and sexual violence" and that a specialist monitoring and listening unit, set up in 2015 as part of an action plan on gender equality, was now being extended with a new project involving students.

Alexandre Kouchner, Camille's half-brother, teaches at Sciences Po. It's probably true, he says, that the book has refocused attention on other forms of sexual assault.

"But it would be untrue and unwise to think this started with a debate about incest," he told me. "This started with the MeToo movement."

Other colleges - business and arts schools - are now facing similar pressures.

The Duhamel affair has also reverberated far beyond one family or one college in opening up a conversation about incest. Incest in France is used to mean sexual abuse by relatives, including those not related by blood.

The association Face à l'inceste, external (Facing Incest) says the number of calls it received this month shot up from 30 to almost 200. Lawyers describe similar jumps in the number of clients wanting to explore legal action.

"I've never seen anything like it," one lawyer told the BBC. "People will often start by saying, 'you know the book by Camille Kouchner? Well, something quite like that happened to me too'."

Earlier this week, a deputy mayor of Paris, Audrey Pulvar, spoke to France Inter radio about revelations that her deceased father had abused three of her cousins as children.

She knew it was true, she said, because "things happened [as a child] that I felt weren't normal. There was a climate I didn't understand."

When you are the daughter of a monster, at some point you wonder if you are not a monster yourself. It's almost automatic

Even President Emmanuel Macron has spoken about the impact of the Duhamel affair.

"The silence built by criminals and cowardice is finally exploding," he said last month. "It's exploding because of the courage of a sister who could no longer stay silent, then the courage of thousands of others who have told accounts of their lives broken in the sanctuary of their childhood bedrooms... No-one can ignore them any longer."

Complicated history

A study conducted last year suggested that one in 10 people in France have experienced incestuous sexual abuse, yet this outpouring of public testimony and public attention feels new.

France's approach to incest - and childhood sexuality - has been complicated by its history, says Fabienne Giuliani, a historian of incest in France.

"Since the French Revolution, we have designed the family as a sanctuary in which the state does not enter," she explained. "During the 20th Century, French society refused to see incest, refused to pronounce the word 'incest', refused to believe children in the courts."

The importance accorded to psychoanalytic theory in France - the idea that children desire their parents - has also affected attitudes here, as did theories that aimed to legitimise paedophilia in the 1970s.

It is currently legal in France for blood relations to have consensual sex as adults, while incest is an "aggravating factor" in cases of child rape and molestation.

Under French law, a rape charge is only possible if there is proof of "force, threat, violence or surprise" - otherwise it is tried as the lesser offence of sexual assault. That applies to children as well, as France has no legal age of consent.

That may be changing. Two bills already going through parliament have put forward plans to remove the possibility that minors can consent to sex. And President Macron has asked his government to draw up similar proposals, introducing an age of consent.

President Macron is pushing for more legal protection for children

"There is something new in France, in this conversation," Alexandre Kouchner told me. "And it's the fact that intimacy has become a political subject. We're looking at a movement that puts what happens to individuals at the forefront of the political debate."

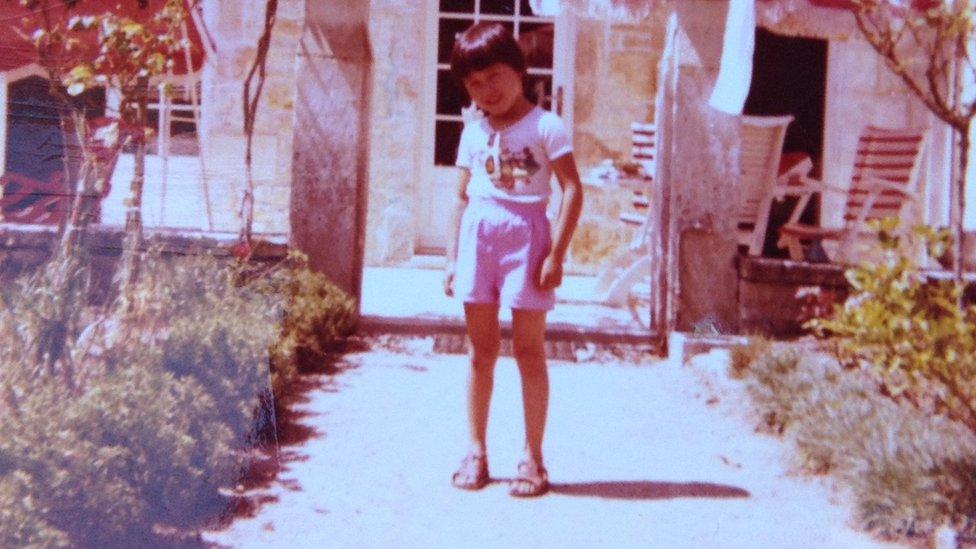

Back in 1986, French television audiences watched Eva Thomas speak about her experiences as an incest survivor. It was the first time anyone here had spoken out in this way without the protection of anonymity.

"I want to stop feeling ashamed," Eva told her interviewers.

"Why didn't you tell your mother?" she was asked. And: "Forgive me, but you let him do this?"

Now there are so many voices, so many campaigns, that some have warned about the danger of different issues being merged together: incest; age of consent; sexual assault; sexual harassment; gay and transgender rights.

But, says Anna Toumazoff, "if everything is getting mixed, it's because it belongs to the same system".

The common link, she says, is the pressure on some parts of society to stay silent.

"Victims have always tried to talk, actually," she told me. "The difference now is that, because of the hashtags and social networks, people are obliged to hear and to answer. That's the difference."

- Published19 January 2021

- Published7 November 2019

- Published19 January 2020

- Published4 March 2020

- Published25 May 2018