A billion new trees might not turn Ukraine green

- Published

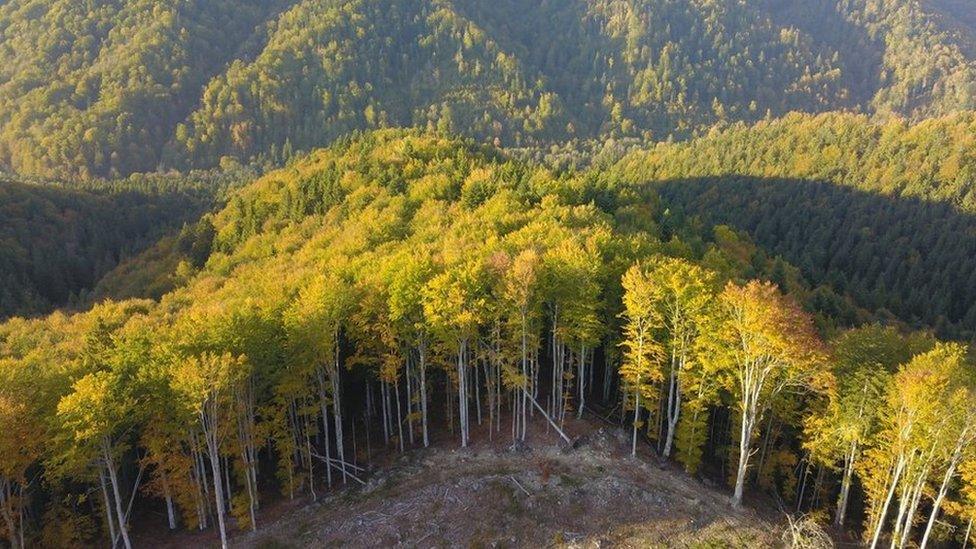

The government hopes the plan will help combat the impact of forest fires and illegal logging

It was an ambitious signal of green intent when Ukraine's President Volodymyr Zelensky declared this month that a billion extra trees would be planted within three years, and a million hectares would be reforested in a decade.

The EU's 27 member states have set a much more modest goal of at least three billion new trees by 2030.

But green experts fear that, far from improving Ukraine's environment, the pledge could have a detrimental impact on biodiversity and natural ecosystems. Up to 70% of Ukraine's lands are used for farming, which is among the highest rates in Europe and a legacy of the collective agriculture of its communist past.

Many of these lands were natural steppes that were turned into fields. Steppes are belts of grassland, usually treeless plains, that stretch from Ukraine through Russia and Central Asia and into Mongolia and China.

"Around 40% of Ukraine's territory is made up of steppe climate zone, but only 3% of the country has preserved the natural steppe ecosystems with their abundant flora," says Olexiy Vasyliuk, from the Ukrainian Nature Conservation Group.

He has spent years mapping the steppes and classifying their flora.

Close to the capital Kyiv lies a forest blooming with flowers. Olexiy shows me a white orchid growing by the path. It is one of 69 types of wild orchid in Ukraine, and some can survive only in their natural habitat of Ukraine's steppes.

"I fear for the fate of such beautiful flowers as this one," he tells me. "I don't feel relieved when the government says it will plant trees in degraded farmlands but won't touch the steppes. Many of Ukraine's steppes are, in fact, degraded farmlands by law."

So if the government really is planning to leave other farmland untouched, the question is where the billion trees will go.

Restoring lost tree cover

Roman Abramovsky, Ukraine's minister for environmental protection and natural resources, tells the BBC the focus will be on "former industrial areas, as well as over 1,500 parks in urban areas".

Planting new forests will take place only in areas where they used to grow before humans started harvesting and before industrialisation, he insists, as well as in woodland hit by fire or disease.

Nowadays almost a tenth of Ukraine's 10.4m hectares of land reserved for forest has no tree cover. Only 16% of its territory is covered with forests - half the proportion of Western European countries such as France, Germany or Spain.

Ukraine has far less woodland than Western European countries

So the president's green pledge has been welcomed by Sergiy Zibtsev, professor at the forestry department of Ukraine's environmental sciences university: "This is what we have campaigned for for a very long time - it's a good decision that will give forestry a boost, and will make the work of forest rangers more prestigious and better paid."

For him the key is to provide financial incentives for forest rangers, local communities and farmers, as other countries such as Costa Rica and China have found out.

Immediate challenges

Ukraine is just starting to look at innovative approaches. Locals would be able to make money from selective timber felling that is friendly to biodiversity, or they could receive subsidies for every reforested hectare and for buying seeds and seedlings.

For environmentalists the immediate challenge for a country like Ukraine in the face of climate change is to preserve existing forests.

Illegal logging is believed to be a major problem in Ukraine

"The new forests will need many decades before starting to store big amounts of carbon," argues Greenpeace biodiversity expert Krzysztof Cibor.

Dmytro Karabchuk, an activist from the Forest Initiatives and Communities NGO, says it can take between 60 and 160 years for a tree to reach full carbon storage.

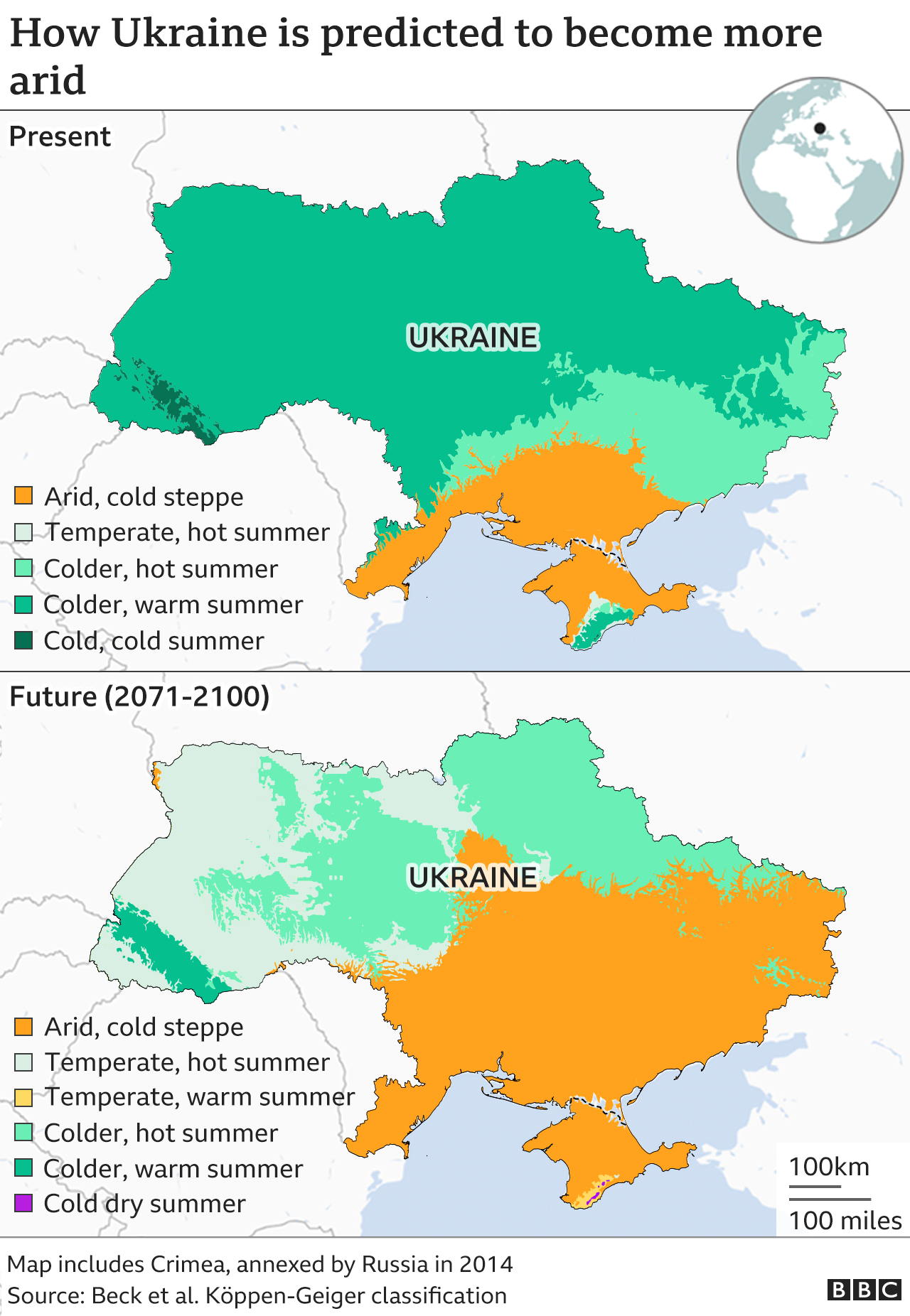

And the risk is that within half a century most of Ukrainian territory may have turned into steppes.

Illegal logging

For Olexiy Vasyliuk and his colleagues at Ukrainian Nature Conservation Group, the first priority is to put an end to illegal logging and reforest the areas that have burned down.

In the forest where we found a white orchid near Kyiv his team have detected recent illegal tree-felling.

Traces of similar illegal logging activity has been found in 45 forest units across Ukraine within recent months.

"By rough estimates, 20-30% of Ukraine's wood cutting is on the so-called black market," says Dmytro Karabchuk. In many cases permits may have been issued but the amount of timber felled is under-reported, he believes.

Ukraine has had some success in recent years in managing its forests as well as in tackling illegal logging.

But it's a long way from the president's eye-catching benchmark of planting a billion new trees.

You may also be interested in:

Why one of Europe's last great beech forests is facing the chop.

Related topics

- Published2 July 2020

- Published21 October 2019