NI 100: Eithne Coyle, the woman who spied for the IRA

- Published

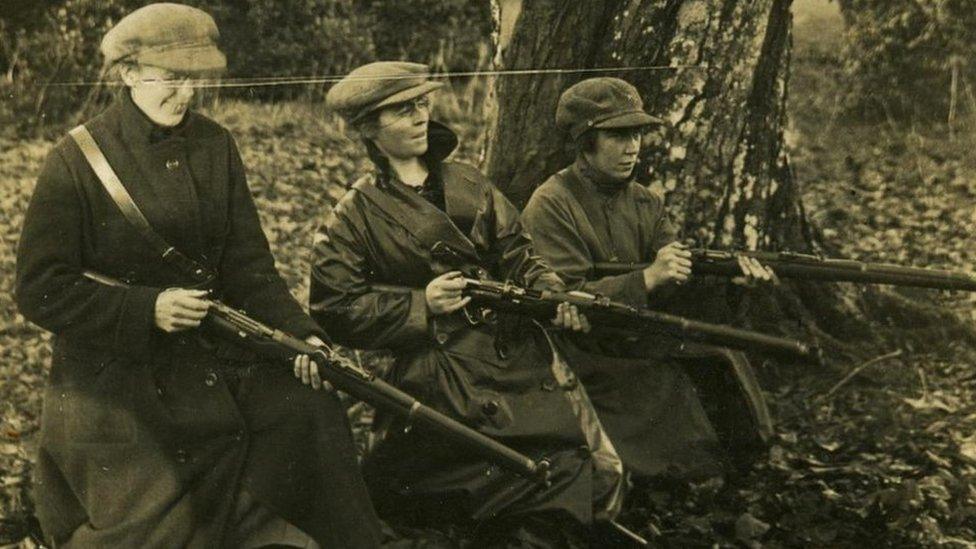

Eithne Coyle (centre) at rifle practice at an IRA training camp in Duckett's Grove, County Carlow, in 1922

She escaped from prison twice, was arrested multiple times and regularly made headlines by holding up Belfast trains at gunpoint.

Eithne Coyle, a leading Irish republican, did things that surprised and even horrified some of her contemporaries a century ago.

The Donegal native took part in several attacks during the Irish War of Independence and the subsequent Irish Civil War.

But her role, and the role of women in general during Ireland's revolutionary period, is overshadowed by their better known male counterparts.

Gender is undoubtedly a factor in why Coyle's story is not more widely known, but it is also why she managed to evade capture on many occasions.

When she was jailed in 1921, Coyle remembers a prosecutor telling her she "had escaped suspicion owing to the fact that I was a woman".

However, she took similar risks to IRA men of her era; endured similar hardships and inflicted similar suffering.

Mae Burke, Eithne Coyle and Linda Kerns pictured during a weapons training session in Duckett's Grove

Coyle was a member of Cumann na mBan (the Women's Council), a female-led paramilitary organisation formed in 1914.

It was set up during the Home Rule crisis to assist the Irish Volunteers - a group of armed republican men, many of whom would soon help to fill the ranks of the emergent Irish Republican Army (IRA).

Coyle joined Cumann na mBan in 1917 and later became its president, a position she held for 15 years.

Very few women were directly involved in armed conflict, but many played significant support roles for men by transporting weapons, gathering intelligence on IRA targets and providing food, shelter and funding.

Coyle however, was among a small number of women who did use guns and in 1952 she spoke to the Irish Bureau of Military History, external about her role.

Aged 20, she joined a branch of Cumann na mBan near her home in Falcarragh, County Donegal, and was soon helping to set up new branches across Ireland.

Women were less likely to be searched or arrested so they were frequently asked to hide guns and carry IRA dispatches.

A portrait of a young Eithne Coyle is among her personal papers held by University College Dublin Archives

By early 1920 - a year into the War of Independence - Coyle was sent to County Roscommon to spy for the IRA.

"My intelligence work covered the reporting of movements of enemy forces, their disposition and strength in various centres and their methods and times of patrol," she said.

Officially, she worked as a Irish language teacher, but admitted her classes were often a "cover" for IRA meetings.

Coyle drew maps and sketches of military buildings which were then used for IRA operations.

These included an attack on Beechwood Barracks and an ambush at Four-Mile House in October 1920, during which at least four Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) officers were killed.

Local magistrates issued a statement expressing their "abhorrence of the murder of these four members of the Roscommon police force" and closed their courts early as a mark of respect to the victims.

'You make me sick'

When Coyle's sketches of Roscommon barracks were found by police she was arrested and ended up in one of the building's cells.

She claimed she was verbally abused and threatened with being shot unless she identified IRA members, but instead of giving up names, she gave cheek to her police guard.

"He was plucking an old hen that he had probably stolen and throwing the feathers in the fire, producing an awful smell," Coyle recalled.

"He used to say: 'You Shine Finers [Sinn Féiners] make me sick.'

"I said: 'You'll be much sicker after you have eaten that old hen.'"

Eithne Coyle delivering a speech at a rally in Dundalk, County Louth, in 1933

She was sent for trial in February 1921, on charges including possession of the barracks plan and a document describing Cumann na mBan's activities.

Coyle did not contest the charges, claiming: "I was reading a newspaper during the whole of the proceedings and I informed the judge in Irish that I refused to recognise the court."

She was sentenced to a year in Dublin's Mountjoy prison, but on Halloween night, Coyle and three fellow inmates escaped.

'Rope ladder'

When a wardress left her keys unattended, the inmates made a wax impression. They passed it to a prison visitor who used it to cut a replica key.

Other inmates then staged a football match to distract staff while Coyle's group escaped, climbing down the prison wall on a rope ladder.

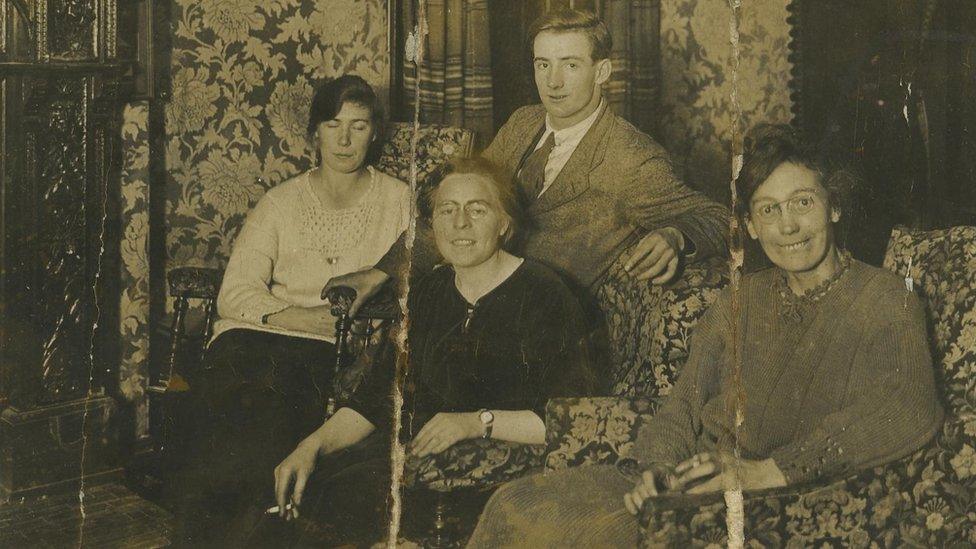

Eithne Coyle (centre) and fellow escapee Linda Kerns (right) took refuge in a doctor's house before being transferred to Carlow

Coyle was then taken to an IRA training camp at Duckett's Grove, County Carlow, where she stayed until the Anglo-Irish Treaty was signed in December 1921.

But like many militant republicans, she opposed the peace deal claiming it reinforced Britain's recent partition of Ireland.

"She was a Donegal woman, so the whole Ulster question would have been something very close to her," says Margaret Ward, a historian and author who met Coyle in the 1970s.

Ms Ward explains that after Cumann na mBan voted against the treaty, one of their tactics was to "reimpose the Belfast boycott in solidarity with the people of the north".

The aim of the boycott was to damage Northern Ireland's emerging economy by disrupting its goods exports, and Coyle was a prolific offender.

While staying at a hotel in Strabane, County Tyrone, in 1922, she "decided to hold up" a mail car carrying Northern Ireland newspapers.

"I had an old revolver which had no trigger, but it did the trick," Coyle recalled.

"I burned all the paper and went back to the hotel to my breakfast."

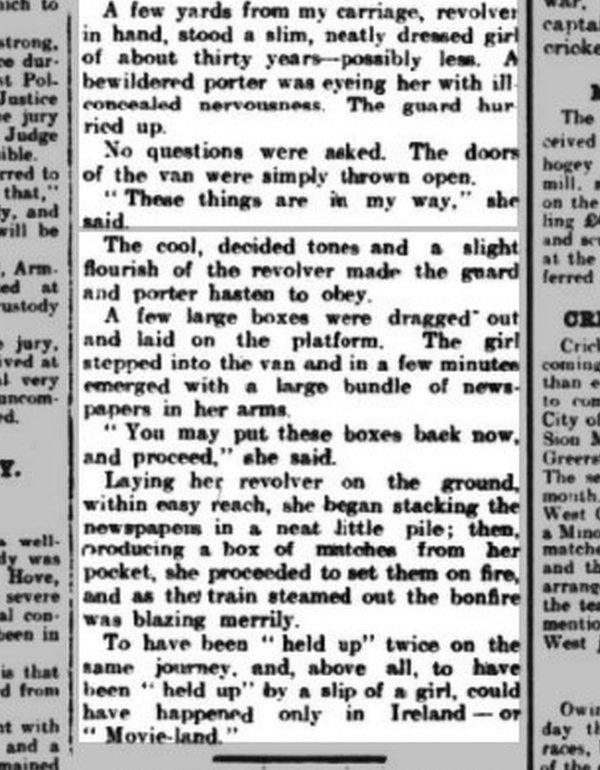

Over the next few weeks, Coyle regularly held up Northern Ireland trains at gunpoint, burning newspapers on railway platforms.

One incident was witnessed by a Daily Mail correspondent, who reported that "only in Ireland or movie-land" could his train be "held up by a slip of a girl".

Ironically, Coyle kept newspaper reports of her train raids, providing them to the Bureau of Military History as evidence of her republican activities.

By June 1922, the republican movement had split in two over the Anglo-Irish Treaty and the country descended into civil war.

Coyle supported the anti-treaty side, continuing to carry dispatches between IRA divisions, which made her a target for the pro-treaty forces of the new Irish Free State.

"I was the first woman arrested by the Free Staters," Coyle claimed, estimating she was detained "about a dozen times" during the Civil War.

She was eventually returned to Mountjoy Prison where she led hunger strikes and other protests against its harsh conditions, later remarking it was "astonishing that any of us survived the hardship".

Her incarceration included a spell in a former Dublin workhouse, from where she staged a second escape alongside other prisoners.

However, they were recaptured the next morning when Free State soldiers spotted them at a train station and Coyle was locked up until after the end of the Civil War.

Three years later, in 1926, she was elected president of Cumann na mBan.

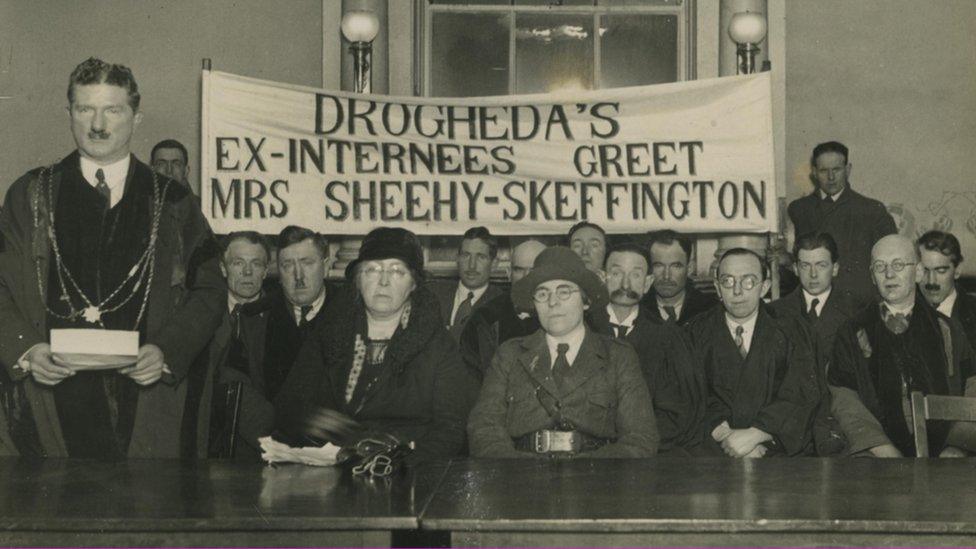

Eithne Coyle (centre right) at a 1933 reception to mark Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington' release from Armagh jail

Cumann na mBan is sometimes described as the "women's IRA" but that is not an accurate characterisation according to Margaret Ward, who says that implies a "wider military role" than was actually the case.

She explains that Cumann na mBan's initial purpose was "specifically to support the men" from the Irish Volunteers during the Home Rule crisis, through non-combative activities like fundraising and first aid.

"But gradually as time went on it became more militarised, and during the War of Independence and the Civil War it was very much attached to the local IRA in an auxiliary capacity," Ms Ward says.

Cumann na mBan was not the first women's organisation in Ireland to support a paramilitary group in defiance of the government of the day.

In his book, Cumann na mBan and the Irish Revolution, Cal McCarthy notes how its founders were influenced by their political opponents in the Ulster Women's Unionist Council (UWUC).

The UWUC was formed in 1911 to oppose Home Rule and became the largest female political movement in Ireland.

These women pledged their support to the men of the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF), a militia group which threatened to resist Home Rule by force.

Ulsterwomen also served in an auxiliary capacity by joining the UVF Medical and Nursing Corps.

Resignation

By the time Coyle became president of Cumann na mBan, its influence was already diminishing, having backed the losing side in the Civil War.

In her late 30s, she married County Donegal IRA man Bernard O'Donnell and had two children.

During this period, she began to step back from Cumann na mBan and tried to resign as president, saying she did not approve of the "bombing of women and children in England by the IRA".

Her resignation was rejected several times, but was finally accepted in 1941.

Ms Ward, who interviewed an elderly Coyle in the mid-1970s, does not remember her expressing any regrets over her own role in IRA attacks.

Instead, the historian recalls a rebellious pensioner who was still "extremely feisty and very supportive of the republican movement in the north during the Troubles".

Coyle died in 1985 and her children donated her personal papers to University College Dublin's Archives.

Image credits:

The five UDC photos above are from the Eithne Coyle O'Donnell Papers and have been reproduced by kind permission of UCD Archives (reference codes P61/9; P61/21; P61/5).

Related topics

- Published11 July 2021

- Published3 May 2021

- Published21 December 2020