Switzerland migrant children demand immigration policy apology

- Published

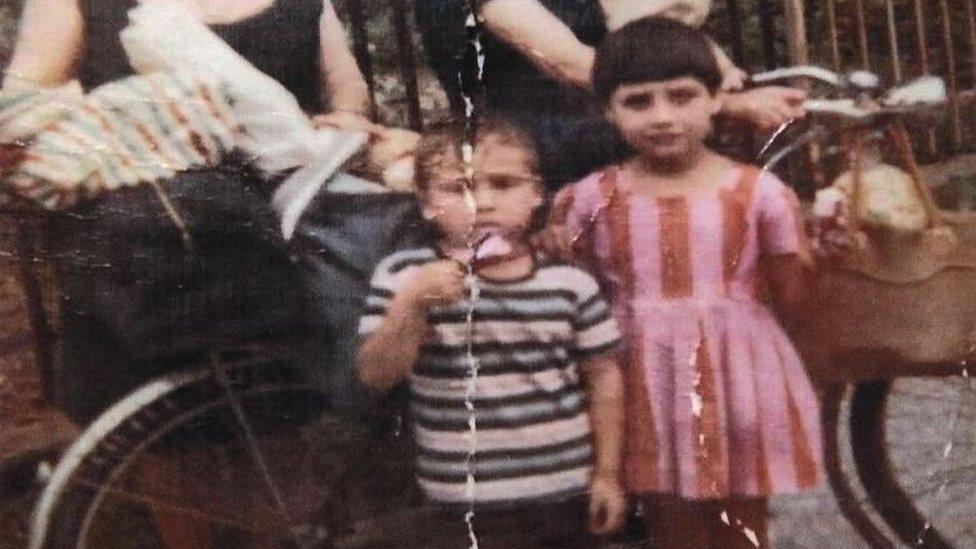

Egidio Stigliano (centre) had to stay hidden when he moved to Switzerland from Italy

Children of migrants who came to work in Switzerland over decades are demanding an apology for a policy they say destroyed families and left many traumatised.

From the 1950s right up until the 1990s, hundreds of thousands of workers - first from Italy, then from Spain, Portugal, and what was then Yugoslavia - made the journey to Switzerland.

They worked in factories, on roads and building sites, in restaurants and hotels. Switzerland's highly successful economy, its good infrastructure, is without doubt due in part to them.

But there were flaws in the system. The migrants were given nine- or 12-month permits; many lived in barracks, their only function in Switzerland was to work.

And family members - including young children - were not allowed. A husband and wife could work together in Switzerland, but, the work permits stipulated, their children had to stay at home.

Forbidden children

Egidio Stigliano, now in his 60s, remembers being taken at the age of three by his grandmother to wave to a train leaving Italy to Switzerland.

"I didn't know my mother was on the train," he remembers. "They thought I was too young to be told what was happening. But my mother wanted to see me one last time."

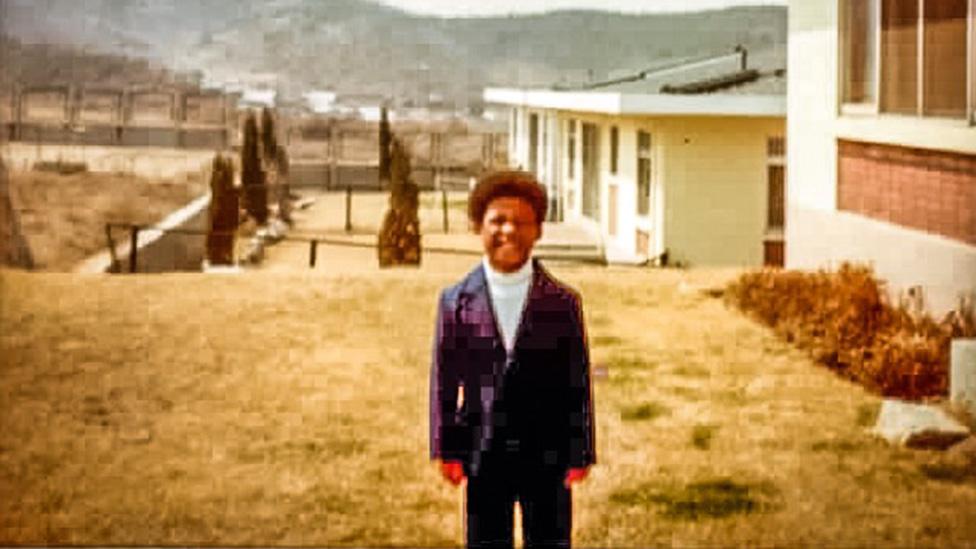

Workers arrived from across Europe - but they weren't allowed to bring their children

The system might have worked if the migrant workers had really been temporary. But their permits were renewed year after year, and some spent their entire lives working in Switzerland.

Melinda Nadj Obonji was just a year old when she and her older brother were left with their grandmother in Vojvodina in Serbia. Despite their "no children" seasonal work permits, Melinda's parents hoped that, once settled in Switzerland, they would be allowed to send for their children.

"They wrote letters to the immigration police, but they were rejected, [the police] were very strict. I think this traumatised them for life, and also us kids of course." Melinda now believes the migrant worker laws "really destroyed our family".

Many might ask why parents desperate to be reunited with their children did not simply go home. But, as is so often the case with migrant workers, the money they earned abroad kept poverty at bay at home.

In Italy, Portugal, or Kosovo, families and even entire villages came to be dependent on the money sent from Switzerland. Meanwhile Switzerland's economy boomed on the back of foreign labour.

Kristina Schulz, a historian and specialist in migration at Neuchatel University, points out that, in the aftermath of World War Two, the Swiss system of recruiting workers from neighbouring countries was viewed very positively.

"Those other countries were war-torn… and Switzerland needed workers. Southern Italy was poor… it was thought it was practically a humanitarian act to have them work here."

But many parents, among them Egidio Stigliano's, could not bear to be parted from their children. They developed secret strategies for coping with the immigration restrictions. Instead of pleading with the authorities to let their children in, they smuggled them in anyway and kept them hidden.

Egidio arrived when he was seven. "From the first moment in Switzerland I hid," he says. "My dad couldn't explain the immigration policy to a child, so he just said, don't let anyone see you, just stay hidden and play in the woods. So that's what I did."

Staying hidden meant not going to school. It meant, when Egidio broke his arm, having to find a doctor who would keep quiet rather than go straight to hospital. But one day, in the woods, Egidio came across another group of children, and could not resist joining in their games.

That evening the police were at the door, telling his parents the child would have to leave. Only the intervention of Egidio's father's boss, who agreed to sponsor him, allowed him to stay.

Egidio Stigliano was not even able to go straight to hospital when he broke his arm

By the 1970s, it is estimated there were thousands of hidden children in Switzerland. Today, in the history museum of the Swiss watchmaking town La Chaux de Fonds, there is an exhibition showing what their lives were like.

Some mothers admit that they locked their children in their apartments during the day, in order to ensure no one saw them. The children were allowed out to play at night. Many families lived in tiny studios because, the exhibition explains, having a bigger apartment more suited to a family would have aroused suspicion.

"It's hard to imagine children locked at home, living alone, no school," says museum director Francesco Garufo. "And it's recent history... it's just yesterday."

Historian Kristina Schulz finds the children's stories all the more shocking given Switzerland's devotion to family life after the war.

"This was the new ideology in Switzerland... the idea of the holy family that needed to be protected, women couldn't vote in Switzerland until 1971, they weren't meant to work, they were at home with the children. So the idea of systematically destroying the families of migrant workers is really astonishing."

Family protests

Gradually, Switzerland's strategy began to be undermined. Migrant workers protested, local police and teachers turned a blind eye to the "illegal" children in their communities, some villages even set up underground schools for migrant children.

The famous Swiss author Max Frisch joined the debate, writing "we wanted workers, but we got people instead".

Children, among them Melinda and Egidio, began to join their parents. Melinda, who was reunited with her parents when she was five, is now a writer and musician in Zurich, Egidio a neuro educator in St Gallen.

In some ways, they count themselves among the luckier ones: after pressure from Rome, the children of Italian migrants were allowed in once their parents had worked more than five years in Switzerland. Melinda's parents finally found a sympathetic Swiss bureaucrat and got permission to bring their children.

But while it was sometimes applied arbitrarily, the law banning children remained, and many families remained divided for decades.

Egidio Stigliano is now finally settled in Switzerland without having to hide

The seasonal work permit was finally abolished in 2002, when Switzerland agreed to join the EU's free movement of people policy. Today, the children of the migrant workers are adults, and many, including Melinda and Egidio, have formed a group demanding at least an acknowledgement of what they went through.

"First, I'd like an apology from the Swiss state," says Melinda.

"I want the story of migrant workers to be in Swiss history books, because thousands of families suffered," adds Egidio.

An honest reassessment of history, and an apology, could be likely. Switzerland has already done this over its World War Two policy of turning away Jewish refugees, and over the way it removed children from single mothers or socially "problematic" families and sent them to work on farms - where they were often abused.

Financial compensation has also been mentioned, but for Egidio recognition is more important. "The time I could have spent with my family, at school, I can't get back. There's no compensation for that."

The reappraisal of history has already begun, in a research project by Kristina Schulz at Neuchatel University, and at the museum in La Chaux de Fonds.

But for museum director Francesco Garufo, it is about more than facing up to Switzerland's past. He thinks, as Europe continues its often negative debate over immigration, that lessons could be learned for the future.

"In a rich country, having thousands of children hidden, without social rights, it's not the model we want today in Europe. So we have to think about this kind of migration choice."

Related topics

- Published2 October 2022

- Published28 April 2022

- Published5 May 2021

- Published7 May 2022

- Published31 July 2021