Nobel Peace Prize: Russian laureate 'told to turn down award'

- Published

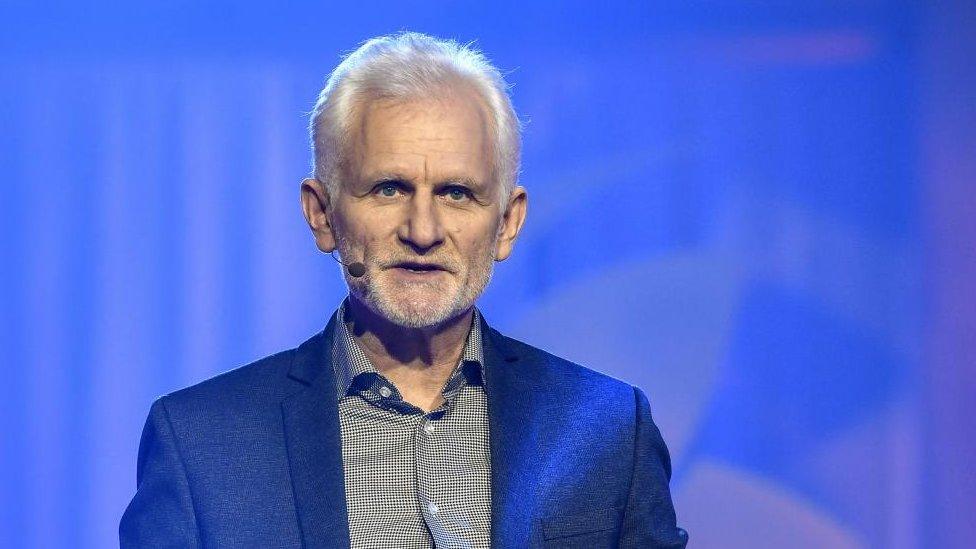

Yan Rachinsky from Memorial: "In today's Russia no-one's personal safety is guaranteed"

The Russian co-winner of this year's Nobel Peace Prize has said Kremlin authorities told him to turn down the award.

Yan Rachinsky, who heads Memorial, said he was told not to accept the prize because the two other co-laureates - a Ukrainian human rights organisation and jailed Belarusian rights defender - were deemed "inappropriate".

Memorial is one of Russia's oldest civil rights groups, and was shut down by the government last year.

The Russian Foreign Ministry has been contacted for comment.

In an exclusive interview with the BBC's HARDtalk programme, Mr Rachinsky said his organisation had been advised to decline the award, but "naturally, we took no notice of this advice".

Despite threats to his safety, Mr Rachinsky said the work of Memorial remained essential.

"In today's Russia, no-one's personal safety can be guaranteed," he said. "Yes, many have been killed. But we know what impunity of the state leads to… We need to get out of this pit somehow."

Memorial has documented historical Soviet repression.

Its first chairman - Arseny Roginsky - was sent to Soviet labour camps for the so-called "anti-communist" study of history.

Announcing the prize winners, the Nobel Committee said that Memorial was founded on the idea that "confronting past crimes is essential in preventing new ones".

Mr Rachinsky called the committee's decision to award the prize to recipients in three different countries "remarkable".

He said it was proof "that civil society is not divided by national borders, that it is a single body working to solve common problems".

Ukrainian Oleksandra Matviichuk refused to be interviewed alongside one of her co-winners, Russian Yan Rachinsky

But the decision to include a Russian recipient has been controversial.

The woman who runs Ukraine's Center for Civil Liberties - another of the prize-winners - refused to be interviewed alongside Mr Rachinsky. The BBC spoke to them separately in Oslo.

When asked why she wanted to do the interview separately, Oleksandra Matviichuk told HARDtalk: "Now we are in a war and we want to make the voice of Ukrainian human rights defenders tangible.

"So I am sure that regardless that we are doing separate interviews, we transmit and deliver the same messages."

The Center for Civil Liberties was recognized for its work promoting democracy in Ukraine and investigating alleged Russian war crimes in the country.

Despite refusing to speak beside her co-winner, Ms Matviichuk praised Mr Rachinsky's work and described Memorial as "our partner".

Memorial had helped the Ukrainian group for years, she said, adding she had "huge respect for all [her] Russian human rights colleagues" who work in difficult conditions.

She also warned that without proper accounting for Russian crimes, peace would not come to Eastern Europe.

Ms Matviichuk called for a new international tribunal to hold President Vladimir Putin and other Russians accountable for their actions in Ukraine, describing the current system as insufficient.

"The question is, who will provide justice for hundreds of thousands of victims of the war crimes?" she asked.

She also accused Russia of using the war as a tool to achieve its geopolitical aims - and committing war crimes in order to win the conflict.

The third Nobel winner, Belarusian human rights defender Ales Bialiatski, has been in prison without trial in his home country since July last year.

He is the founder of the country's Viasna (Spring) Human Rights Centre, which was set up in 1996 in response to a brutal crackdown of street protests by Belarus's authoritarian leader Alexander Lukashenko.

Mr Bialiatski previously spent three years in prison and was released in 2014.

Ms Matviichuk described her co-laureate as "an extremely brave person, so he will continue this battle even in prison".

Watch HARDtalk on the BBC News Channel (UK) at 14:30 GMT on 10 December, 00:30 on 11 December, or 00:30 or 04:30 on 12 December.

Or view the programme on BBC World News at 01:30 or 08:30 GMT on 11 December, or 04:30, 09:30, 15:30 or 19:30 on 12 December.

This year's third Nobel winner, Ales Bialiatski (pictured in 2020), is in prison in Belarus

- Published7 October 2022

- Published7 October 2022

- Published21 June 2022