Ecuador neighbours reopen borders after 'coup attempt'

- Published

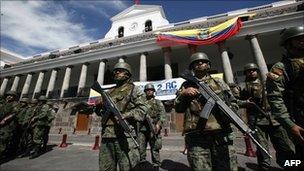

Ecuador's military was put in charge of public order after a state of emergency was declared

Peru and Colombia have reopened their borders with Ecuador, a day after President Rafael Correa accused police and the opposition of a coup attempt.

Ecuador's neighbours closed crossings in a show of support for Mr Correa, who had to be rescued by soldiers from a hospital surrounded by angry police.

Afterwards, the president vowed in a TV address to punish those responsible.

The national police chief has resigned in the wake of the unrest, which left two people dead and dozens injured.

After General Freddy Martinez stepped down, President Correa appointed Patricio Franco as new police chief in his place, and ordered him to reform the country's police.

The revolt was triggered by a new law cutting bonuses and benefits for public servants, including police and military personnel.

Mr Correa, a 47-year-old US-trained economist, took office in 2007 and won a second term in 2009 - despite a decision to default on $3.2bn of loans which caused widespread fiscal problems for his government.

'False accusations'

On Friday, South American heads of state held an emergency meeting in Argentina and issued a resolution saying they "energetically condemn the attempted coup and subsequent kidnapping" of President Correa.

They also called for those responsible to be tried and convicted, and warned that in the event of new threats to order, they would immediately close frontiers and air traffic, suspend commerce and cut off energy supplies and other services to Ecuador.

But with the streets quiet in their neighbour's main cities, and the military in charge of public order under a state of emergency, Colombia and Peru announced that they had reopened their frontiers.

It was still not clear whether Mr Correa was targeted in a coup attempt, as he has claimed, or whether it was simply a protest that spiralled out of control.

The president was trapped for more than 12 hours in a hospital, where he was being treated for the effects of tear gas fired at him by angry police and soldiers when he confronted them at an army barracks in the capital.

It was only after army special forces moved in under cover of darkness, that he was freed. Shots were fired outside the building and two people were killed, including at least one civilian, according to the Ecuadorean Red Cross.

Later, there were jubilant scenes at the presidential palace, where Mr Correa addressed supporters, telling them it "was the saddest day of my life".

The BBC's Will Grant explains how the siege unfolded

He alleged that the uprising was not just a dispute over benefits.

"There were lots of infiltrators, dressed as civilians, and we know where they were from," the president said.

"The people of Lucio Gutierrez were there, provoking, inciting to violence," he added, referring to the leader of the opposition Patriotic Society Party (PSP).

In a TV interview, Mr Gutierrez denied "the cowardly, false, reckless accusations".

The president also said there would be "a deep cleansing of the national police", and that he would "not forgive nor forget" what had happened.

"Those people made the institution look so bad by attacking their fellow citizens, abusing the weapons given to them by the society to which they belong, and dishonouring the police uniform."

"All those who can be identified will be punished accordingly."

Despite the apparent end of the crisis, Foreign Minister Ricardo Patino said the government could not yet "claim total victory".

"We have overcome the situation for now, but we can't relax," he told a news conference in Quito. "The coup attempt may have roots out there, we have to find them and pull them up."

On Wednesday, one minister had said the president was considering disbanding Congress because members of his Country Alliance had threatened to block proposals to shrink the bureaucracy.

Ecuador's two-year-old constitution allows the president to declare an impasse and rule by decree until new elections. However, such a move would have to be approved by the Constitutional Court.

The BBC's Will Grant, in Venezuela, says Mr Correa could still choose to rule by decree in an effort to stay in control in the immediate future.

- Published1 October 2010

- Published1 October 2010

- Published27 February 2013

- Published30 September 2010