Cholera outbreak in Haiti 'stabilising'

- Published

The BBC's Laura Trevelyan: "Cholera is alarming at the rate in which it spreads"

Health officials have said there are signs that the cholera outbreak in central Haiti may be stabilising.

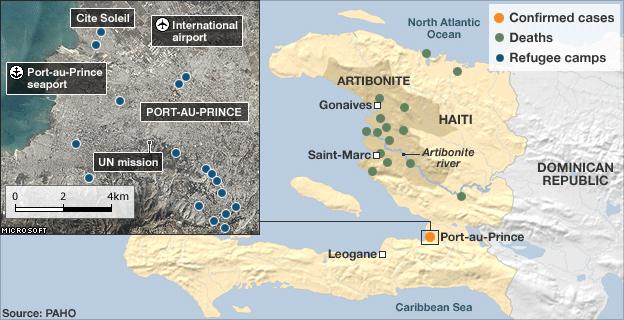

More than 250 people have died and more than 3,000 have been infected, but the rate of increase has slowed.

The UN and aid agencies are aiming to educate Haitians about how to prevent the spread of cholera, as well as setting up dedicated treatment centres.

The disease is seen as a serious threat to 1.3 million earthquake survivors living in tent camps near the capital.

There are also major concerns for the slum areas of Port-au-Prince, which made up some 80% of the city even before the earthquake struck, the United Nations says.

Five cholera cases were detected on Saturday in Port-au-Prince, but they were quickly diagnosed and isolated.

Haiti has not seen a cholera outbreak for 100 years, UN spokeswoman Imogen Wall said, with many people frightened by the news of the outbreak and unsure of what steps to take to avoid the disease.

Poor sanitary conditions make the camps and slums vulnerable to cholera, which is caused by bacteria transmitted through contaminated water or food.

Cholera causes diarrhoea and vomiting, leading to severe dehydration, but can kill quickly. It is easily treated through through rehydration and antibiotics.

Anxious wait

On Sunday, the director general of Haiti's health department, Gabriel Thimote, said the number of people who had died in the outbreak was rising, but more slowly than during the previous 24 hours.

"We have registered a diminishing in numbers of deaths and of hospitalised people in the most critical areas," he told reporters.

"The tendency is that it is stabilising, without being able to say that we have reached a peak," he added.

Mr Thimote also expressed optimism that the outbreak could be contained.

"It's not difficult to prevent the spread to Port-au-Prince."

The five victims isolated in the capital had become infected in the Artibonite region - the main outbreak zone - and then travelled there, the UN's Office for the Co-ordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) said.

"These cases thus do not represent a spread of the epidemic because this is not a new location of infection," it explained, adding that the development was nevertheless "worrying".

Sarah Jacobs, of the charity Save The Children, told the BBC that although there were encouraging signs, the situation remained highly dangerous.

"There are still hundreds of thousands of people living in extremely bad conditions in the capital and the key thing now is to prevent this disease from spreading," she said.

Ms Jacobs said that informing the public would be crucial.

Haitian officials said more households were following advice on drinking clean water and taking care with personal hygiene.

However, the BBC's Laura Trevelyan in Saint-Marc in Artibonite says some people are still using water from a river believed to be at the centre of the outbreak.

And at the town's hospital, doctors said they were seeing about the same number of cases as they did on Saturday, our correspondent says.

Outside, crowds of people continue to wait anxiously - some are desperate to be admitted, others are clamouring for news of their relatives, she adds.

Only those with the most severe cases of diarrhoea are being admitted.

The worst-hit areas of the outbreak are Saint-Marc, Grande Saline, L'Estere, Marchand-Dessalines, Desdunes, Petite-Riviere, Lachapelle, and St-Michel de l'Attalaye.

A number of cases have also been reported in the city of Gonaives, and towns closer to the capital, including Archaei, Limbe and Mirebalais.

Officials hope to set up cholera treatment centres in Artibonite and the neighbouring Central Plateau region, and in Port-au-Prince, where patients can be isolated. International specialists are also being flown in to help.

"We must gear up for a serious epidemic, even though we hope it won't happen," Nigel Fisher, the UN's deputy special representative in Haiti, told the Reuters news agency.

This is the first time in a century that cholera has struck the nation, which has enough antibiotics to treat 100,000 cases of cholera and intravenous fluids to treat 30,000, according to the UN.

- Published25 October 2010

- Published24 October 2010

- Published25 October 2010