Haiti cholera outbreak prompts fresh UN aid plea

- Published

Fears are growing of a major outbreak in Port-au-Prince

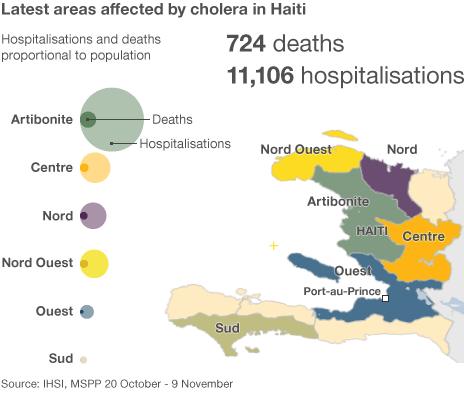

The UN has appealed for nearly $164m (£102m) to fight a cholera outbreak in Haiti which has now claimed 724 lives.

UN spokeswoman Elisabeth Byrs said that unless funds were provided, "all our efforts can be outrun by the epidemic".

She said the disease had so far infected at least 11,125 people in five of Haiti's 10 districts.

Aid agencies are battling to contain cholera in the capital Port-au-Prince, amid fears it will spread through camps housing 1.1m earthquake survivors.

More than 80 people have died in the past 24 hours across the country, according to the health ministry.

High fatality rate

Ms Byrs, of the UN's Office for the Co-ordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), said the funds will be used to bring in more doctors, medicines and water-purification equipment.

"We absolutely need this money as soon as possible," she said.

Stefano Zannini, head of mission for Medecins Sans Frontieres in Haiti, said on Friday that hospitals in Port-au-Prince are overflowing and patients may have to be treated in the streets.

"We are really worried about space," he said.

"If the number of cases continues to increase at the same rate, then we are going to have to adopt some drastic measures. We are going to have to use public spaces and even streets. I can easily see this situation deteriorating to the point where patients are lying in the street, waiting for treatment. At the moment, we just don't have that many options."

The World Health Organization said on Friday it did not expect the epidemic to end soon.

"The projections of 200,000 cases over the next six to 12 months shows the amplitude of what could be expected," said spokesman Gregory Hartl.

He said that the current fatality rate of 6.5% was far higher than it should be.

"No-one alive in Haiti has experienced cholera before, so it is a population which is very susceptible to the bacteria," he said. "Once it is in water systems it transmits very easily."

The outbreak began in Haiti's Artibonite River valley in mid-October and at first seemed to have been contained.

But Hurricane Tomas, which struck earlier this month, flooded rivers believed to be contaminated with cholera and submerged refugee communities already struggling to survive.

The disease is spread by contaminated drinking water or food, but is treatable with oral or intravenous rehydration and antibiotics.

Aid agencies say access to clean water is a major problem, and they are struggling to get the message across to Haitians to seek medical help as soon as cholera-like symptoms appear.

Even before the earthquake only 40% of Haitians had safe drinking water.

Haiti's besieged health services have been warned to expect a different scale of disaster if cholera takes hold in the capital, which was devastated by January's earthquake that left more than 250,000 people dead.

"We greatly fear a flare-up in the capital which would be serious given the conditions in the camps," Claude Surena, president of the Haitian Medical Association, told AFP news agency.

Aid delayed

Meanwhile, the first portion of US financial aid for reconstruction in Haiti is on its way, more than seven months after it was promised to help the country re-build after the earthquake in January.

The $120m (£74m) - about a tenth of the amount pledged in total by the US - has faced several delays.

Only 37.8% of the money pledged by all countries for 2010-11 has been delivered to the poverty-stricken nation.

- Published11 November 2010

- Published10 November 2010

- Published23 November 2010

- Published9 November 2010

- Published9 November 2010