Is Haiti election set for new twist thanks to Aristide?

- Published

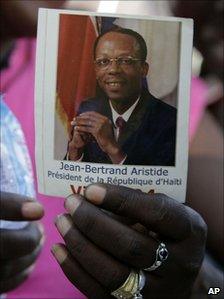

Fromer president Jean-Bertrand Aristide: Still part of the election story?

On Sunday, a grandmother takes on a pop star for the right to run a country.

It is set to be a strange end to what has been no ordinary election in an extraordinary year-and-a-bit for Haiti.

And there could be a further twist to the tale amid speculation that the country's former president, Jean-Bertrand Aristide, is set to return from exile in South Africa in the coming days.

Mirlande Manigat, a 71-year-old grandmother-of-three and wife of a former president, and Michel Martelly, a 50-year-old singer known to his fans as "Sweet Micky", are the two left standing after an election process with all the intrigue of a soap opera.

Mrs Manigat and Mr Martelly have been cast in very different roles.

The former first lady is a Sorbonne-educated academic with considerable political experience. She is popular among the middle-class.

Sweet Micky is a star performer of kompa (Haitian dance music) who likes to drop his trousers on stage. The youngsters who cheered at his concerts now cheer with equal passion at his political rallies.

Mr Martelly's supporters are "young men star-struck by the gangsta bling image," says Andrew Leak of the Haiti Support Group.

"I don't think either candidate actually stands for anything in reality."

Their policies are indeed more similar than their personalities.

Both have spoken about increasing access to education, better health care, reorganising the agricultural sector and creating jobs.

They have also campaigned on improving law and order and giving Haitians living abroad a greater say in the country's affairs.

"The difference between Manigat and Martelly is that the former is part of the traditional political class in Haiti, whereas Martelly definitely isn't," says Mr Leak.

"Whoever is elected, it will make not one iota of difference to the 85% of Haitians who live in absolute poverty."

The Haitian government may simply lack the money to implement many of the candidates' policies.

Coming home?

The country's limited resources have been channelled into a massive reconstruction effort after an earthquake in January 2010 killed tens of thousands and reduced much of the capital, Port-au-Prince, to rubble.

And there is another urgent problem to fix - a deadly cholera outbreak which began before last November's first round of voting and is still not under control.

For some Haitiains, Jean-Bertrand Aristide is still their president

But for many, there is only one person who truly represents the interests of Haiti's poor.

Jean-Bertrand Aristide, a former-priest-turned-populist-politician, became Haiti's first democratically elected president in 1990.

He lasted only a few months before a military coup forced him to flee the country. He returned in 1994, was re-elected president in 2000, but had to leave Haiti again after a rebellion in 2004.

Speculation has been growing that he is about to come home from South Africa.

He would not be the only long-lost character to have made a dramatic, soap opera-style reappearance.

Another former president, Jean-Claude "Baby Doc" Duvalier, returned to Haiti in January after a quarter of a century in exile, which prompted rumours that Mr Aristide would also return.

If he does, what impact would this have on Sunday's vote?

Historian Philippe Girard has written several books on Haiti, including one about Mr Aristide's political career.

"Aristide still enjoys a lot of popular support among the masses, particularly in the slums of Port-au-Prince.

"His return would likely be followed by large demonstrations, complaints that he is not on the ballot and civil unrest large enough to potentially derail the elections."

And this is precisely why the Americans have asked Mr Aristide to delay his comeback until after 20 March, saying his reappearance before the run-off would be "destabilising".

Election or selection?

But some think the US position amounts to foreign meddling in Haiti's democratic process.

An open letter to The Guardian newspaper earlier this month accused foreign powers of interfering in the election , external and called for the 20 March vote to be cancelled.

Writers, academics and interest groups signed the letter. Andrew Leak from the Haiti Support Group was among the signatories.

"Ordinary Haitians refer to these elections as the 'selections' - they understand very well that the run-off candidates have been chosen in advance by the international community," he says.

Mr Aristide's party, Fanmi Lavalas, was excluded from November's first round on a technicality.

Haiti's presidential palace is still lagely in ruins a year on from the quake

The vote was won by Mrs Manigat, with initial results putting Michel Martelly in third place, behind the candidate supported by the incumbent President Rene Preval.

Then a team of international monitors said Mr Martelly would have finished second had it not been for fraud and the government-backed candidate was forced to withdraw.

"An orderly transfer of power to a cleanly-elected person would be the top US priority," says Philippe Girard.

The main concern is rebuilding Haiti after the earthquake and the new president must have a good relationship with the foreigners who are paying for much of the reconstruction, he explains.

This might be one of the few certainties in an election process that has never been easy to predict.

The outcome of Sunday's vote, and whether or not Mr Aristide will be there to see it, are equally uncertain.

Soap opera writers could not have scripted it any better.

- Published20 March 2011

- Published3 March 2011

- Published8 February 2012

- Published12 January 2011