Colombia's Farc rebels: End to kidnap a new start?

- Published

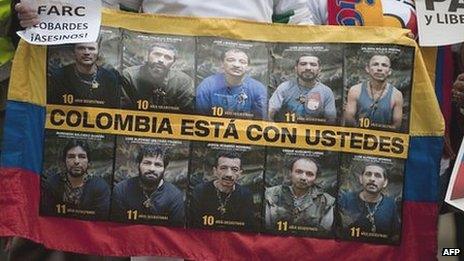

The long plight of Farc hostages has resonated in Colombian society

In an unprecedented concession, Colombian rebels have pledged to end their practice of kidnapping for ransom and release the hostages they hold, hoping to re-open the doors to dialogue as the civil conflict enters its 48th year.

In a communique published on the rebel-friendly website Anncol, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Farc) announced an end to kidnapping.

"Much has been said about the retention of people, men or women of the civilian population, for financial ends for the Farc to sustain our fight.

"With the same will expressed before, we announce that from this date we forbid this practice in our revolutionary conduct," the statement said.

President Juan Manuel Santos, who has made the release of all kidnapping victims a condition for peace talks, responded cautiously to the rebel announcement, making it clear that the door to talks is not about to spring open.

"We value the announcement of the Farc to renounce kidnapping as an important and necessary step, but it is not enough," he said via Twitter.

Rebel empire

Almost exactly a decade ago, the last round of negotiations between the government and the Farc ended in abject failure.

The then president, Andres Pastrana, had been forced to the negotiating table on very unfavourable terms.

When he started peace talks in 1999, the rebels controlled a third of the country. They were able to destroy major military bases, take a provincial capital and ambush the best troops the army had.

To get the Farc to sit down and talk, President Pastrana had to grant the guerrillas a 42,000 sq km (16,000 sq miles) safe haven.

This became, from 1999 to 2002, the centre of the rebel war machine and drug trafficking empire, allowing the Farc to receive training from foreign groups and establish contacts with Mexican drug cartels.

In 2012, the situation could not be more different.

Colombia's military has had success in targeting the rebel leadership in recent years

Since 2002, the Farc rebels have suffered a series of reverses and been defeated strategically, their aim of overthrowing the state now little more than a mirage.

Their leadership has been decimated. While in the last two years the Farc have managed to regroup and step up their actions, they can only put 8,000 fighters into the field, half their number in 2002.

Thanks to better intelligence and continuous air strikes by the US-backed Colombian military, the rebels are unable to concentrate their fighting forces in one place to launch large-scale actions.

So now the government holds all the cards, and is wary of starting peace talks for several reasons.

The first is that the Farc have traditionally used dialogue, in the 1980s and 1990s, to build up their strength and political relevance.

Secondly, there is no legislation in place under which negotiations could be held that the rebels would accept.

The last rebel groups to negotiate, back in 1991, received full amnesty after handing over their weapons.

Now, under international law, those guilty of crimes against humanity cannot be granted a blanket amnesty.

Extortion

The Farc will also be very wary, recalling what happened when the illegal right-wing paramilitaries of the United Self Defence Forces of Colombia (AUC) surrendered to the government between 2003 and 2006.

Most of their leadership ended up being extradited to the US to face drug trafficking charges.

The abandoning of kidnapping by the rebels has more political then financial implications for the Farc.

The Farc have been blamed for a series of recent deadly attacks

Kidnapping for ransom as a source of income for the rebels has dropped significantly.

In 2002, rebels were responsible for the majority of the 2,882 kidnappings registered, making millions of dollars in ransoms.

Last year, fewer than 300 abductions were registered - the Farc were blamed for just 77.

Lack of ransom money may affect some guerrilla units that operate in areas where there are no drug crops or cocaine smuggling routes.

But the rebels are likely make up the difference with extortion, which has become the second most important source of Farc income after illegal narcotics.

Outrage

Politically, the announcement has greater significance.

For the last 15 years, the Farc have had a policy of kidnapping politicians and members of the security forces, whom they have described as "prisoners of war".

These hostages, of whom they still hold at least 10, have been used as bargaining chips in a proposed prisoner exchange.

The idea has been to secure the release of hundreds of imprisoned rebels in return for the hostages.

This strategy has been an unmitigated failure for the Farc, not only because no rebels have been released from prison, but also because it brought international condemnation.

This was particularly the case with their highest profile hostage, former presidential candidate Ingrid Betancourt, who was kidnapped in 2002 and rescued by the security forces in 2008.

However, President Santos has to be careful.

Support for a negotiated settlement to the civil conflict is growing, even as the rebels step up their actions once again.

A source in the presidential palace was cagey about how the government would handle the Farc announcement, but did say that it was likely that the electoral cycle would play a large part in any start to negotiations with the rebels.

The next presidential elections are in 2014, giving Mr Santos plenty of time to further hammer the Farc and get some new legislation in place before he offers the rebels their chance to sit down at the peace table once again.

- Published26 February 2012

- Published27 May 2013

- Published29 August 2013

- Published24 February 2012

- Published17 February 2011