Ecuador split on asylum for Wikileaks' Julian Assange

- Published

_afp.jpg)

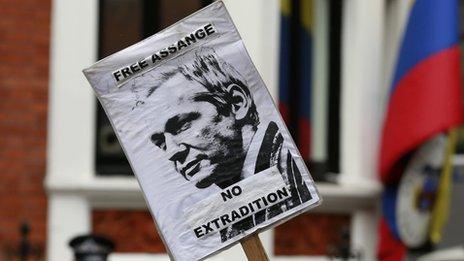

Protesters have come out in support of Julian Assange in the capital Quito

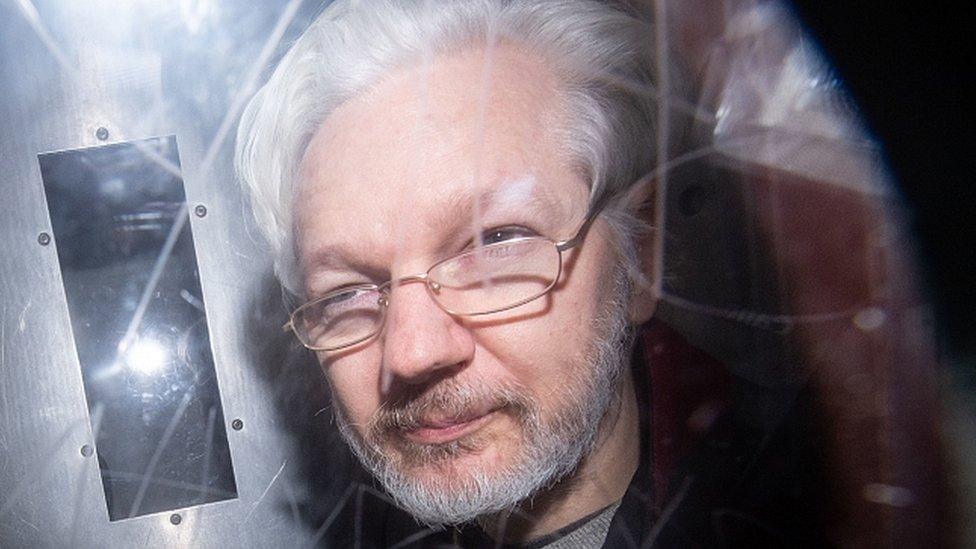

A day after the decision to grant him asylum in Ecuador, Julian Assange's face looks out from every news stand in Quito.

If Ecuadoreans did not know who the Wikileaks founder was, or why he has become the thorn in the side of their country's relationship with the UK, they will doubtless get to know their new house guest in the coming weeks.

And this even though he is still a long way off from making it into Ecuador.

Just around the corner from the foreign ministry in Quito is a small street restaurant called The Clay Bowl.

As thin steaks and chicken breasts sizzle on the grill, most customers remain resolutely unimpressed with the entire diplomatic debacle.

Questions about Mr Assange are generally answered with a bemused shake of the head.

But the young chef turning the steaks at the grill is more forthcoming.

"I know him and I don't think we should judge other people," he says.

"Only God can judge people and if we're in a position to help someone who needs it, well, then they're very welcome."

Then he echoes the sentiment of his president, saying: "We're free to do as we please."

It is that freedom to grant diplomatic immunity and asylum to whoever they please that has galvanised President Rafael Correa's supporters.

One man on a busy Quito thoroughfare says Mr Assange is being persecuted by the US for simply "telling the truth" and it was right for Ecuador to support him.

Deputy Foreign Minister Rafael Quintero told the BBC that Mr Assange wanted to come to Ecuador as he felt "his human rights, civilian rights, civic rights and political rights would be protected".

"We only hope that the government of the United Kingdom will respect the sovereign decision of the Ecuadorean peoples," he said.

Many people in Ecuador share the feeling that the move to grant Mr Assange asylum was just, and that the British Foreign Office had implicitly threatened the country over the right to revoke the embassy's diplomatic status under the UK's Diplomatic and Consular Premises Act of 1987.

Concern

But as the dust begins to settle from the initial announcement, some Ecuadoreans are also beginning to worry.

One officer worker in Quito said there could be a knock-on effect on jobs in Ecuador, and feared the Assange decision might alienate friends around the world. "Then we, the workers, would be punished", she said.

Some Ecuadoreans think President Correa's own record on free speech is far from spotless

For others, there is a certain irony that Mr Assange has turned to Mr Correa for help as a fellow defender of free speech.

Cesar Ricaurte is the director of Fundamedios, a press freedom organisation.

"I think this is a sort of public-relations exercise," he says of the Assange decision. "It's an effort by the government to 'wash its face' - the face we see all the time in Ecuador."

Mr Ricaurte says journalists in Ecuador who are critical of the government operate in a "climate of constant aggression and hostility".

"Every week, there's something new. The government recently published photos of journalists considered to be 'enemies' in the state-run media, something which obviously puts those journalists at risk."

He also claims the government has closed some 20 media outlets under Mr Correa, including radio stations and a TV channel, using what he called "arbitrary administrative pretexts". Others have been directly punished for their anti-government editorial lines, Fundamedios claims.

Tension with Britain

Nevertheless, the representative for Reporters Without Borders in Ecuador, Eric Samson, says a word of caution should enter the debate.

The idea that Mr Assange is at risk of a second extradition from Sweden to the United States, where he could face charges which potentially carry the death penalty, is legitimate, Eric Samson argues.

"It is a real fear, and can't be dismissed," he says.

The entire diplomatic dispute is taking place in a climate of heightened tension with the UK following its handling of Argentina's reiteration of its claim to the Falkland Islands or Malvinas, around the 30th anniversary of the conflict.

Certainly, many think that the tone of the communication about the little-known 1987 law was an implicit threat, and one which automatically raises tensions with South America, where many remember the interventionist role of the West during the Cold War only too well.

In the end, as Mr Samson points out, the issue of Mr Assange facing questioning over sexual-assault allegations in Sweden is getting further and further away from the discourse in Ecuador.

"There is a series of interests at play here and not all of them have to do with Julian Assange or Wikileaks," he says.

- Published17 August 2012

- Published25 June 2024

- Published16 August 2012