Colombia: How would a peace deal change the country?

- Published

President Santos was re-elected in June 2014 on a promise to drive forward peace talks with the Farc

Peace negotiations between the Colombian government and the country's largest rebel group, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Farc), aimed at ending five decades of armed internal conflict, have been under way for two years.

Since the formal talks were launched in Oslo in October 2012, the two sides have reached agreement on three of the six points on their agenda.

President Juan Manuel Santos has said that he would like to see a deal signed by the end of the year, but the rebels recently accused him of rushing the negotiations.

With the talks now in their 30th round and attacks by the rebels continuing - unlike during previous negotiations the two sides have not signed a ceasefire - Colombians are getting increasingly sceptical about the president's ambitious timetable.

Colombia's armed conflict

•An estimated 220,000 killed

•More than five million internally displaced

•230,000 fled their homes in 2012

•6.2 million registered victims

•About 8,000 Farc rebels continue fighting

Sources: Unit for Attention and Reparation of Victims, Colombian government

Meanwhile, President Santos has been trying to garner international support for a post-conflict Colombia.

So how would Colombia change if a permanent peace accord were to be reached?

Economy

President Santos has predicted that "peace alone will bring almost two percentage points annually to our already booming economic growth".

Colombia's oil industry is one of the sectors that has been hit by rebel attacks

While Colombia's economy has been growing at a rate of about 4% in the past decade, analysts say that growth could have been double that if it had not been for the armed conflict.

The Colombian Research Centre for the Analysis of Conflict predicts that a peace deal would "strengthen formal employment, hasten poverty reduction and improve quality of life".

Unemployment continues to be a major problem in Colombia, which in 2011 had the highest levels in the whole of Latin America.

Although the government announced last May that the unemployment rate had dropped to its lowest level in 14 years, at 8.8% it still remains almost double that of neighbouring Ecuador.

In a study entitled ""What would Colombia gain economically from peace?", the think tank says that an end to the armed internal conflict would boost investment in particular in areas so far shunned by risk-adverse investors and drive up the value of land and assets in those regions.

But peace, or rather what Colombian politicians call the "post-conflict process", also comes at a cost.

Roy Barreras, who jointly chairs the peace commission in the Colombian senate, recently put this cost at $45bn (£28bn) over the next decade.

He said major investment was needed in areas such as land distribution, registration and management, as well as in local government and agriculture, if peace was to be achieved in areas which for a long time have had a minimal state presence.

But he told the senate that figures by the non-profit think tank, the Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP), suggested this cost would be offset by a predicted $49bn in extra revenue created by investors' regained confidence in a peaceful Colombia.

His sentiments were echoed by Daniel Mejia, director of the Research Centre on Drugs and Security at the University of the Andes in Bogota, who also thinks the cost of implementing a peace deal could be recouped within a decade.

"We have to see the peace accord as an investment which is costly in the short run but which has very important benefits in the medium and long term," he told me.

Security

Although the two sides entered formal negotiations two years ago, there has been no bilateral ceasefire, despite pressure for one from the Farc.

The security forces estimate that the Farc still have about 8,000 active fighters

President Santos argued that a ceasefire agreed during previous negotiations held between 1998 and 2002 allowed the rebels to regroup and re-arm to emerge stronger than before.

So while the talks have been going on in Havana, the Cuban capital, attacks have continued unabated.

The Bogota-based non-governmental organisation, Foundation for Peace and Reconciliation, says that in 2013 there were on average 182 clashes per month between the Farc rebels and the security forces.

The two sides have said that a permanent peace deal would trigger an immediate ceasefire and a decommissioning of weapons.

The security forces have orders to continue fighting the rebels until a permanent peace deal is agreed

Figures from the Foundation for Peace and Reconciliation, external suggest the Farc have been good at sticking to unilateral ceasefires they have called in the past.

During a Christmas truce they declared between 20 December 2013 and 20 January 2014, there were only four violations, the foundations says.

This suggests orders passed down from Farc negotiators in Cuba were largely followed by the fighters in the field, its researchers say, boding well for a post-conflict Colombia

However, the Farc is not the only group that is a security problem in Colombia.

Colombia's second-largest rebel group, the National Liberation Army (ELN), commands some 1,500 fighters and is also involved in armed conflict despite having started exploratory peace talks with the government.

National Liberation Army rebels and government negotiators have held exploratory talks

But there is also a number of violent criminal gangs which engage in extortion, drug trafficking, illegal mining and murder.

There are fears in the security forces that Farc fighters could be lured over to these gangs rather than surrender their weapons.

Drug trafficking

One of the three points on which the government and rebels have reached agreement is the illegal drugs trade, one of the main sources of funding for the Farc.

Cocaine production in Colombia has fallen, but the country is still among the top three producers in the world

The two sides said they would eliminate all illicit drug production in Colombia should a final peace deal be reached.

Mr Mejia, at the Centre on Drugs and Security, thinks that a final peace accord could "drastically diminish the drugs trade in Colombia", provided the government manages to widen the state presence in areas that have been neglected for decades and implements the points it has agreed with the rebels on rural development.

But security analysts fear the retreat of the Farc from the drugs trade could create a vacuum into which Mexican cartels could move.

Civil society

There is no doubt Colombian society has been adversely affected by five decades of armed conflict, with an estimated 220,000 people killed and more than five million internally displaced.

Five decades of conflict have created a climate of distrust

Andrei Gomez-Suarez told me a peace deal could radically transform the social fabric of Colombian society.

The lecturer on Colombian politics at the University of the Andes says a peace accord would create a context for sectors of Colombian society who still view each other with distrust, such as unions, businesses, and the security forces, to start working together to generate trust - an essential part of any healthy society.

He says a peace deal would allow more room for leftist social movements - currently often stigmatised as guerrilla supporters - to express their concerns about the key problems affecting Colombian society.

According to 2012 World Bank figures, Colombia is the seventh most unequal country in the world, with inequality levels similar to those found in Haiti and Angola.

And while poverty levels have dropped from 47.7% in 2003 to 32.7% in 2012, income inequality, which fuels social tension, has remained virtually unchanged.

The countryside has suffered most from the presence of the guerrilla, with a lack of investment in infrastructure and education leaving rural dwellers with little chance to better themselves.

Rural areas have been those worst hit by the decades of conflict

In the northern Colombian province of Choco, more than two thirds of the population live in poverty, according to Colombia's national statistics office.

And in Cauca, where the Farc have a strong presence, poverty levels run at 62%.

Mr Gomez-Suarez argues that a peace deal would allow Colombians to shift their attention from immediate security threats to more long-term goals and tackle these pressing issues.

He thinks that a peace deal would allow the security forces to concentrate on fighting criminal organisations.

The eastern border area has seen a growth in criminal gangs which smuggle subsidised goods from Venezuela to Colombia and drugs the opposite way.

The presence of the gangs has increased insecurity in such border towns such as Cucuta and driven many into the illegal smuggling business as well as driving local producers and merchants out of business.

Criminal gangs have also increased their presence in such places as the port town of Buenaventura.

Residents have told the BBC they are afraid to go out after a spate of particularly gruesome killings and a growing number of disappearances.

A peace accord and the shift of resources away from battling the rebels and towards fighting common crime could increase citizens' safety in such crime hotspots, Mr Gomez-Suarez argues.

Increased security would in turn allow civic and community groups - targeted by criminals who see them as a challenge to their authority - to flourish and enrich the democratic process.

Timeline: Five decades of rebellion

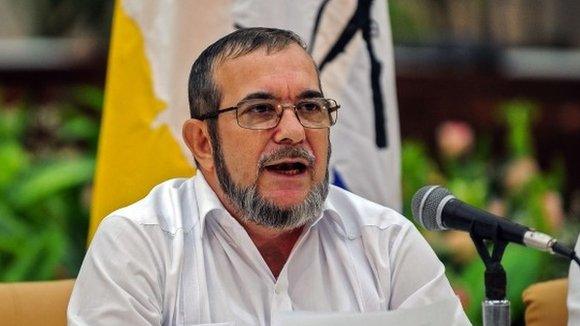

The Farc was founded in May 1964 by a group of Marxist revolutionaries including Manuel Marulanda

•1964: Farc rebel group founded as an armed wing of the communist party

•1965: Farc fighters seize the town of Inza, the first time they take control of an urban centre

•1980: Farc rebels abduct 22 soldiers, the first time they use kidnapping as a strategy to further their aims

•1984: Government of Belisario Betancourt and Farc sign a ceasefire

•1986: Ceasefire crumbles when 22 rebels are killed by the military, the rebels retaliate with an ambush on soldiers

•1991: Peace talks are held in neighbouring Venezuela and later moved to Tlaxcala, Mexico, where they fail in 1992

•1996-1998: Farc are at their strongest, kidnapping about 200 members of the police and military

•1998: Government of Andres Pastrana engages in peace talks, agrees to grant the rebels a safe haven the size of Switzerland

The safe haven granted to the Farc gave the rebels time to regroup and re-arm

•2002: Peace process breaks down. Farc rebels seize presidential candidate Ingrid Betancourt

•2008: Senior rebel leader Raul Reyes killed in a bombing raid, Farc founder Manuel Marulanda dies of natural causes

•2012: Farc announces end of kidnapping for ransom

•Oct 2012: Peace talks are launched in Oslo and move to Havana, Cuba in November 2012

Farc negotiators have been engaged in talks with the government in Cuba since November 2012

- Published9 April 2014

- Published3 October 2013

- Published24 September 2015