The child soldiers who escaped Colombia's guerrilla groups

- Published

Reporter Tom Esslemont met young boys trained by the Farc - Colombia's largest guerrilla group.

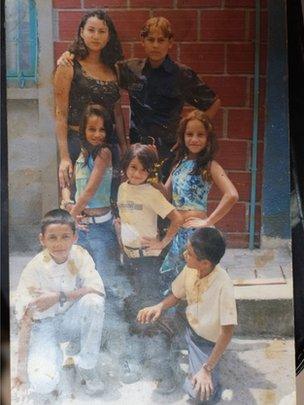

The faded photograph on Yineth Trujillo's book case tells the whole story.

She stands at the back, looking tall and broad-shouldered next to her younger brothers and sisters.

In the photo she is 17 and has long dark hair. She's muscular, unsmiling, almost masculine. Her eyes are swollen.

"I had been crying all day," she tells me. "It was the first time I had seen my family in years. They had given me up for dead."

She is one of thousands of child soldiers to have demobilised in the last 15 years.

Most of them were recruited by Colombia's biggest left-wing guerrilla groups - the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Farc) and the National Liberation Army (ELN).

Two years before the picture was taken, Ms Trujillo had ceased to be a child soldier with the Farc, the largest of Colombia's left-wing guerrilla groups

Yineth Trujillo fought with Farc for three years: she was 12 years old

Today, at 27, she is a sophisticated woman with a radiant smile and two young, happy daughters - a far cry from the little 12-year-old girl who was brainwashed by the guerrillas and made to act as an informant.

"They gave the boys lots of training in handling explosives and me in intelligence gathering," she recalls.

"The Farc really wanted to recruit [girls] for this reason, because no-one suspects a little girl. A little girl can transport money, weapons, drugs much more easily."

She said she was made to perform abortions on other female recruits, who were not allowed to have children, in order to keep them focused on their guerrilla duties.

"This was the thing that scarred me most," she explains.

"The women [recruits] think that if they get pregnant, then they're lucky and they will be free. They are mistaken. It doesn't matter how long a woman has been pregnant. It could be two or eight months. Either way, she will get an abortion," Ms Trujillo said.

Her resilience is similar to that of many other former combatants I spoke to at a government-run rehabilitation programme, based at a farm in western Colombia.

Harrowing past

Yineth Trujillo (at back, left) spent five years as a child soldier with the Farc guerrilla

Government figures suggest that the rate of desertion by combatants rose by 40% in the first six months of this year, compared with the same period last year.

The rise coincided with the start of peace talks between the Farc and the government, though it is impossible to say if there is a link.

Some of the demobilised children are taken to the farm. Its exact location is kept secret to protect them from the rebel factions they recently deserted.

We were the first foreign journalists to be allowed there to talk to the children. We have changed their names to protect their identities.

Carlos, who wears a purple T-shirt, told us how - at the age of 15 - he spent up to five hours in battle at a time, seeing his friends shot dead next to him.

Juan, now 16, showed us where he was shot and injured in the head while he was with the Farc. From the age of 12, he was a unit commander, meaning he and his subordinates were tasked with guard duties.

Yolanda, a delicate girl with long black hair, also 16, described how she fell asleep while on guard duty one night. Her punishment was being made to carry heavy rifles during the next patrol.

To help ease the trauma of what they have experienced, the children may now spend several months on the farm, until they have shown proper signs of recovery and safe homes are found for them.

They grow vegetables, feed the animals and learn to trust strangers again.

'No choice'

The rehabilitation centre's child welfare psychologist, Carolina Maya Rivera, says many of the child soldiers had little choice about being recruited.

"They were led to take up these weapons and uniforms not because they wanted to, but because there was no other option," she says.

I ask her how difficult reforming those who were trained to kill could be.

"These kids are neither victims nor murderers. People are not good or bad. This is just something that happens to them," she explains.

The experiences of many of those on the farm are so raw that they are still focused on their day-to-day lives, though they seem a determined bunch.

One older ex-combatant, Leonardo, who was drafted by the Farc at the age of 11 after being tortured by the army, explains that he would like to go into politics.

He says that in 20 years' time, he would like to be president.

Hearts and minds

The children's stories paint a picture of brutality in Colombia 50 years since its civil conflict began.

The government accuses the guerrillas of continuing to recruit children, though over the years all sides have used brutal tactics.

As well as trying to end the war through dialogue, the government continues to try to defeat the guerrillas on the battlefield.

The Farc have lost many members, but the military believes they are increasingly dependent on a malleable and ever younger fighting force.

In Meta province, we saw a military hearts-and-minds campaign in full swing: a marching band paraded around town and a football match was organised for the town's young.

Bicycles and stereos were given away as prizes. War-weary rank-and-file soldiers in T-shirts and baseball caps handed out balloons.

Maj del Rio runs the army's campaign to prevent the recruitment of child soldiers

Maj Armando del Rio, who runs the campaign, says it is squarely aimed at preventing the recruitment of children.

"These rural areas are prime targets for the illegal armed groups. It is rather ironic but we know that what we are doing is for the good of the Colombian kids," he said.

But not everyone shares Maj del Rio's view,

Jose Luis Campo, leader of a charity for former child soldiers, Benposta, says he has seen cases in which children have been used as informants by the military.

"There have been many cases [...] of boys and girls that were threatened by the Farc because they found out they were doing intelligence operations on the payroll of the army [or] the police," Mr Campo says.

Deputy Minister of Defence Jorge Bedoya denies the allegation: "No, it is illegal, it is prohibited, in Colombia and by our own internal framework, using minors in the way you mentioned."

Dream within reach

Back in her home near the capital, Bogota, Ms Trujillo is now writing a book about her experiences. She is also helping to rehabilitate other ex-combatants with the government's reintegration agency.

Yineth Trujillo now lives in Bogota with her two daughters

She clearly is pleased with the help the authorities have given her to adjust to normal life, but says more needs to be done.

"The more people demobilise, the bigger the need for a better education, for more houses, and more business so it will be easier to get a job," she says.

"Everybody has to work for this, not just the government or the Farc, but all Colombians."

On the wall is a framed picture showing her with her two young daughters, all of them smiling.

It encapsulates her dream for a fulfilling family life, a dream which now looks achievable.

Full-length versions of Tom Esslemont's investigation can be seen on Newsnight on BBC2 on Thursday and in Our World this weekend on BBC World News.

- Published3 October 2013

- Published24 September 2015

- Published29 August 2013