Shaky truce: Is El Salvador's gang war really on hold?

- Published

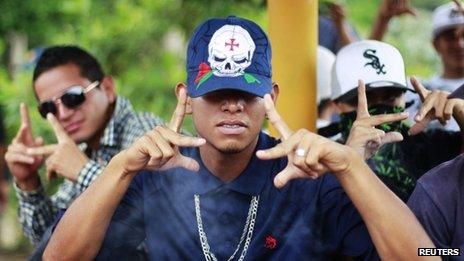

El Salvador's street gangs have a reputation for ruthless violence

"It's the numbers versus the letters: 18 against MS."

While meaningless to most people outside Central America, those words, spoken by a peace negotiator, evoke a conflict that has plagued the region for over two decades.

Barrio 18 is one of Central America's biggest drug gangs. Mara Salvatrucha - MS for short - is its main rival.

Between them they have tens of thousands of members, and their near constant street-level war has claimed hundreds of lives per month since the early 1990s.

Deadly record

Until recently, El Salvador had the highest per capita murder rate in the world. That title has now passed to its unfortunate neighbour, Honduras.

In part, the change has been attributed to a 2012 truce declared by rival Salvadoran gang leaders.

Mara Salvatrucha and Barrio 18 agreed a halt to hostilities in 2012

Initially, the ceasefire yielded results. In 2012 El Salvador's murder rate dropped from a staggering 14 murders a day to around five.

The truce was hailed as a blueprint for other countries in the region with gang problems.

But opponents now say the pact has ceased to work. The say gang crimes other than murder, such as extortion and rape, have continued unabated.

And, in a sign the shaky agreement is beginning to crumble, the month-on-month murder rate is also creeping up again. In November 2013, it reached 11 murders per day.

Family grief

The Castellanos are just one of the many families who have lost a loved one during this supposed ceasefire.

Jose Hernan worked as a mechanic in a neighbourhood controlled by the Mara Salvatrucha.

One Sunday, he ventured into an area run by the Barrio 18 gang with two friends to buy food. Weeks later their mutilated bodies turned up by a roadside.

Rosa Candida is Jose Hernan's mother-in-law. Sitting in a dusty yard where chickens peck among the rubbish, she shows me photos of Jose Hernan, insisting he had no gang connections.

"He was a good man, a good father, husband, a good son-in-law. He won me over from the start," she says.

Bullish optimism

Despite experiences like that of Rosa Candida, the chief negotiator of the truce, Raul Mijango, is adamant it is working.

"Over the past 20 months, we have been experiencing in El Salvador a new form of tackling violence, and the results have been highly successful," he says bullishly.

He says that thanks to the truce and the subsequent drop in the murder rate, 4,874 lives have been saved. "If this initiative hadn't been launched, we'd be mourning those lives," he argues.

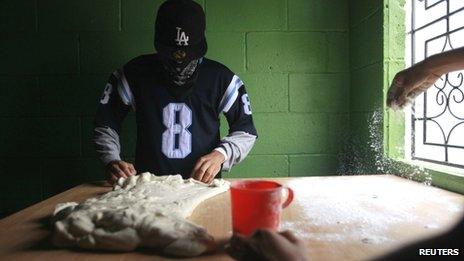

A bakery set up in Ilopango was intended to provide gang members with an alternative income

Mr Mijango also points to the creation of "violence-free municipalities" as a further achievement.

Ilopango, a notorious neighbourhood of the capital, San Salvador, is one of the municipalities where local gangs have made a pact to stop the violence.

It is largely in the hands of the Barrio 18, but Mayor Salvador Ruano insists the gangs are respecting the truce.

A bakery and a chicken farm have been set up to provide gang members with small businesses to keep them from resorting to extortion.

However, on the day we visit them, both enterprises are empty and devoid of life.

Mr Ruano admits his neighbourhood is far from perfect, but assures us that the spirit for a lasting peace is there.

"There is no book to tell us how to do this, what the next step should be. We're building something here and sometimes make mistakes. But when we fall, we get back up, dust ourselves off and carry on."

Urban terror

In a Mara Salvatrucha-controlled neighbourhood called Ciudad Delgado, we are led to a safe house where the main leaders of the gang are gathered.

With tattoos on their necks, faces and torsos, these are the men who have terrorised El Salvador for years.

But today, their rhetoric is polished and political. If the ceasefire is faltering, they tell me, it is due to circumstances beyond their control.

Gang leader Julio Cesar says that that very morning a body had been dumped not two blocks from where we were talking.

He says that such murders take place without the gang's prior knowledge or authorisation, but are being blamed on the gang in order to destabilise the peace agreement.

Chagi is one of the Salvatrucha gang leaders based in Ciudad Delgado

"Some people don't like what's happening because they have interests at stake," he argues.

"A good example is that the private security firms here are run by the police themselves," he says, alleging that some of the officers have little interest in the truce working.

Fellow gang member Blue, who lost a hand throwing a grenade in the 1990s, says part of the problem is a lack of viable alternatives for young people.

"It's difficult because the system doesn't give you any space nor opportunities. If I could get a job where I could make $400 (£245) a month, I'd work," he says.

Back in Rosa Candida's yard, such justifications for violence ring hollow.

Rosa Candida lost not only her son-in-law, but also her husband, who was killed four years ago in gang-related violence.

Her voice cracking, she says the truce has made no difference. "There's more violence now than before.

"They say that those neighbourhoods like Ilopango are free of violence, but that's where most of the killings are. So what is this ceasefire then? It's not doing anything."

- Published20 December 2013

- Published28 May 2013

- Published21 November 2012