Indigenous Bolivia begins to shine under Morales

- Published

The indigenous people have a new-found sense of confidence

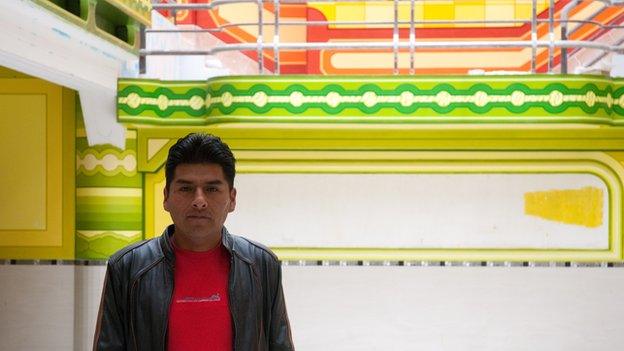

In the highland city of El Alto, which sits just above La Paz, Aymaran architect Freddy Mamani Silvestre is a busy man.

He is known as the king of Andean architecture, building dozens of houses that are changing the face of the El Alto which has, up until now, been full of simple red-brick and concrete houses.

Using bright coloured paint, geometric patterns and folkloric elements, he says he has broken traditional architectural rules.

Freddy's creations are certainly impressive. Two-storey dance halls with capacity for 1,000 people, chandeliers imported from China and flashing lights coming out of every luminous-green pillar he builds.

"With my architecture I want the world to know that Bolivia has its own identity," he says.

"There have always been rich Aymaras. The problem was they didn't identify with it. Now, with this architecture they come to the fore saying, 'We are Bolivians, we are Aymara and we can show off our Indigenous Bolivians' new confidenceidentity.'"

Freddy's work encapsulates the huge transformation in indigenous identity that has swept through Bolivian society in recent years following the election of Evo Morales as president in 2006.

Indigenous president

Freddy Mamani Silvestre uses traditional designs in his work

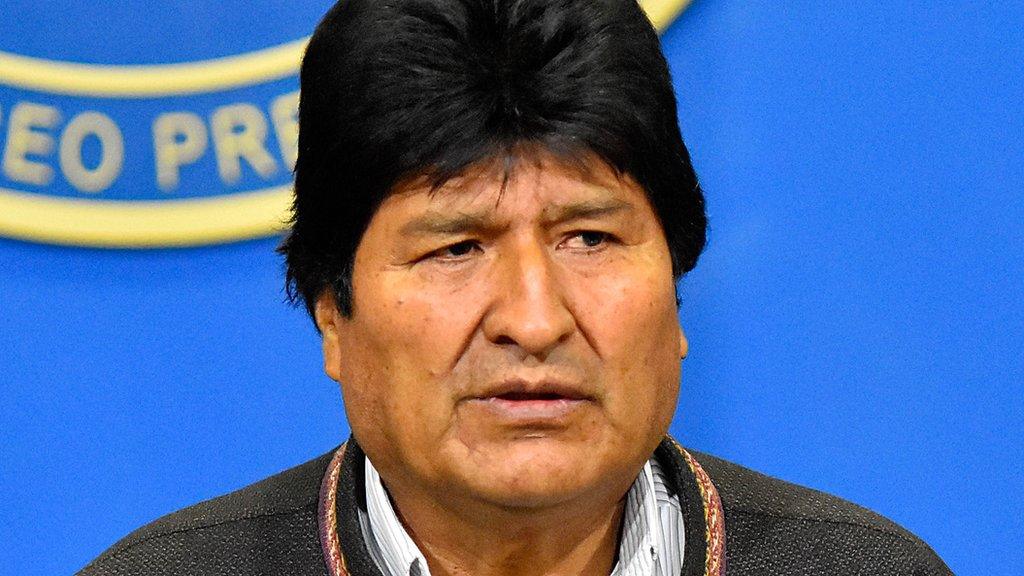

Mr Morales represented profound change for Bolivia. Not only was he the country's first indigenous president, he came to power promising a better deal for the nation's indigenous people, who make up nearly two-thirds of the population.

One of his biggest achievements was passing a new constitution, external in 2009 that included comprehensive rights for Bolivia's indigenous communities - 36 identified groups in total.

The constitution explicitly recognised their cultural identities and customs, as well as collective ownership of land, the granting of more regional and local autonomy and - controversially - the right of indigenous groups to carry out community justice under their own legal system.

It is seen by many experts as one of the most comprehensive constitutions for indigenous rights in the world.

"It's a very significant document," says Maxwell Cameron, who teaches comparative and Latin American politics at the University of British Columbia.

"It was almost like going back to the creation of Bolivia by Simon Bolivar in the 19th Century and saying, 'Well how can we create a more inclusive democratic country?'"

Bolivian population:

Estimated to be 10.2 million in 2009

In the 2001 census, 62% of Bolivians (over the age of 15) identified themselves as indigenous

This is the largest proportion of indigenous people in any Latin American country

The largest indigenous groups are Quechua (30%) and Aymara (25%)

Other groups include Guarani (1.5%), Chiquitano (2.2%) and Mojeno (0.85%)

There are 36 groups in all.

But it has not been a smooth ride. While the western media may call him a firebrand, he is also seen as a pragmatist.

It is this pragmatism that has led some to question his commitment to the indigenous cause.

Indeed, some critics even point out that although he is an Aymaran Indian, he does not speak the language and therefore is not a true indigenous Bolivian.

Some also point to his background as a cocalero, arguing that coca growers are more focused on capitalism than they are on indigenous rights.

"This government is the most anti-indigenous government in the history of contemporary Bolivia," says Luis Tapia Mealla, a philosopher and one of Mr Morales' critics.

"The government's politics is one of extracting natural resources."

In 2011, this debate came to a head. After protests, Mr Morales cancelled the building of a road through an Amazon reserve known as TIPNIS.

The route was meant to link the Brazilian Amazon with ports on the Pacific coast of Peru and Chile but the project was shelved after protests.

Indigenous tribes said that it would destroy their homeland; other communities saw it as a much-needed way to boost economic development.

"There is a tension between the exploitation of natural resources on the one hand and the respect for indigenous land rights on the other," says John Crabtree, academic and author of Bolivia: Process of Change.

"That is a tension not just in the TIPNIS but all over - particularly in lowland Bolivia where oil and gas are to be found."

Some say TIPNIS is just one of many examples where Mr Morales has broken his promises.

"There's no substance to the constitution," says Raul Prada, a former deputy minister in Mr Morales' government.

The document renamed the country as the Plurinational State of Bolivia, external, to recognise Bolivia's diversity, and that included important steps for indigenous autonomy.

But, according to Prada nothing has changed.

"It's in the constitution but the government is not practising it. They've just continued with building a nation-state, just as the previous governments did."

Saturnina Quispe says racism is still a problem

Work still to be done

Not everybody agrees. Saturnina Quispe, an Aymaran sewing teacher at the women's centre at El Alto, says Mr Morales has had a huge impact.

"We women in traditional dress never used to be able to enter offices - we were only allowed as far as the door," she says.

But she admits the fight is not over yet. "Racism has got better but not totally. We still have to work hard. It shouldn't exist but it does."

While not all of Mr Morales' investments are solely about the indigenous communities, they are very much about creating a country that is open to every Bolivian.

One of the most visible signs of that is Mi Teleferico - a new cable car system and Bolivia's answer to an urban metro system.

These space-age bubbles in the sky, complete with wifi, connect up the wealthy city of La Paz with indigenous El Alto.

They are two cities that, despite their proximity, are often seen as worlds apart, but the cable cars that travel up and down the mountain are blurring those boundaries.

Mi Teleferico has been paid for by a government flush with cash.

With one of the largest natural gas reserves in South America, as well as an abundance of minerals, Bolivia has done well out of the commodity boom - last year, the economy grew 6.5%, its fastest pace in decades.

At the same time, Bolivia has undergone a nationalisation programme, the aim being to keep as much money in Bolivia as possible.

Coupled with stable macroeconomic policy, even the International Monetary Fund, an institution long criticised by Mr Morales, has praised the country's prudent approach to its finances in recent years.

But the work is not over for Mr Morales. The constitution marked a major step, but there is criticism from some quarters that economic development goes against indigenous interests.

No doubt a growing economy that has benefited people has helped keep his critics at bay but if commodity prices fall, Bolivia will be vulnerable - a slowing economy would see Morales' popularity wane too.

- Published13 October 2014

- Published10 November 2019

- Published7 February 2023