WW1 Coronel: An unlikely naval battle remembered

- Published

The German ships, commanded by Maximilian von Spee, outgunned the Royal Navy's vessels

If you had to guess where the British suffered their first naval defeat of World War One, what would you say? The North Sea, maybe? Or somewhere in the North Atlantic?

The answer actually lies in the southern Pacific Ocean, over 12,000 km (7,500 miles) from northern Europe, off the coast of Chile.

One hundred years ago this weekend, on 1 November 1914, the British Royal Navy confronted a German squadron outside the port of Coronel, close to Chile's second city of Concepcion.

The Germans won a resounding victory, sinking two of the four British ships with the loss of over 1,600 lives. Not a single German sailor died.

Not only was it Britain's first naval defeat of WW1 but it was its first anywhere in the world in over a century, dating back to the war of 1812 against the United States.

Britannia had ruled the waves for generations, and the defeat at Coronel sent shock waves through its empire and beyond.

"Within days it was all over the world," says Nick Hewitt, a historian from the National Museum of the Royal Navy in Britain.

"The Times of London reported it, the New York Times reported it, it was front page news in Australia," he told the BBC.

The port of Valparaiso is still busy, and continues to host warships from naval powers such as the US

"This was a superpower being humiliated. This sort of thing just didn't happen to the Royal Navy.

"It had a genuinely catastrophic impact on British morale."

The British responded quickly and forcefully. They despatched ships from the North Sea down to the South Atlantic and confronted the Germans at the Falkland Islands five weeks later.

This time, the British won. They sank four German ships, killing more than 1,800 sailors. All their own ships survived.

Trade target

Descendants of some of the British sailors who died at Coronel have travelled to Chile this week to pay homage to them.

On Friday, they sailed out to the site of the battle and laid wreaths at sea.

On Saturday, they took part in a remembrance ceremony in the port itself.

Chilean navy cadets took part in a memorial service for those who died

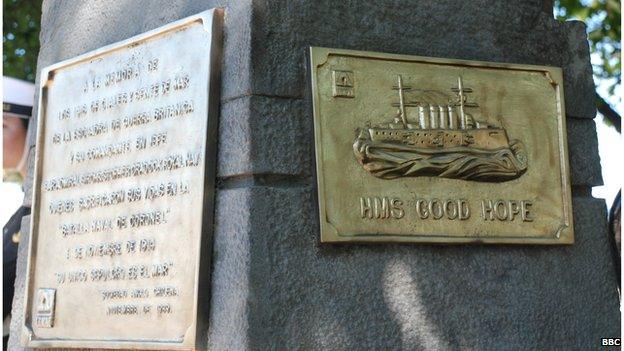

Leigh Merrick, a retired navy officer, was one of those who made the journey. His grandfather was a reservist stockbroker on the HMS Good Hope, one of the British warships sunk during the battle.

"I think he saw joining the navy as a chance to escape and to see a bit of the world, certainly not expecting it would end here, in the Battle of Coronel," said Mr Merrick.

"I promised my father before he died that if I was still around I'd come out for the 100th anniversary. I think he and my grandfather would be very pleased that I made it."

Memorial to those who died at the Battle of Coronel

Another relative, Liell Francklin, said he was the grandson of the flag captain of the HMS Good Hope.

"On Friday we went to the site where we believe the ship lies and we all distributed little mementos," he said.

"I brought some soil from home, which was also my grandfather's home, to drop overboard. It was very emotional."

For many people, the fact that the British and Germans were even in the area at the time comes as something of a surprise.

But it was part of an important trade route back then.

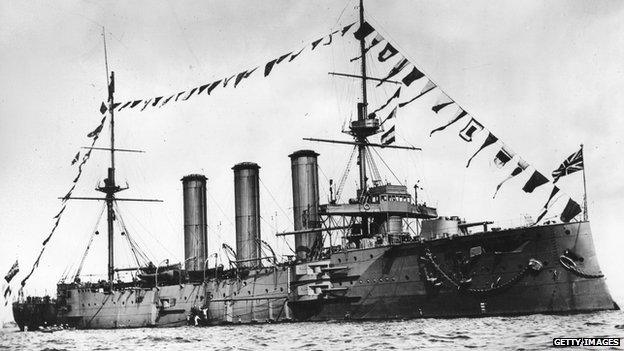

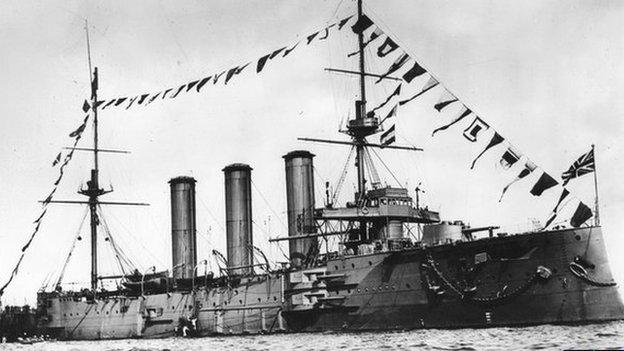

The British cruiser HMS Monmouth was outdated compared with its German counterparts

The Panama Canal had only just opened and until then, ships crossing from the Atlantic to the Pacific had to round the bottom of South America and travel up the Chilean coast.

"It was all about merchant trade," Hewitt said. "The Germans were trying to disrupt British trade to hamper their war effort."

Funeral flowers

The German squadron that fought at Coronel was under the command of Maximilian von Spee, an experienced admiral.

"They were crack ships, their crews have been together for years and they knew exactly what they were doing," Hewitt said.

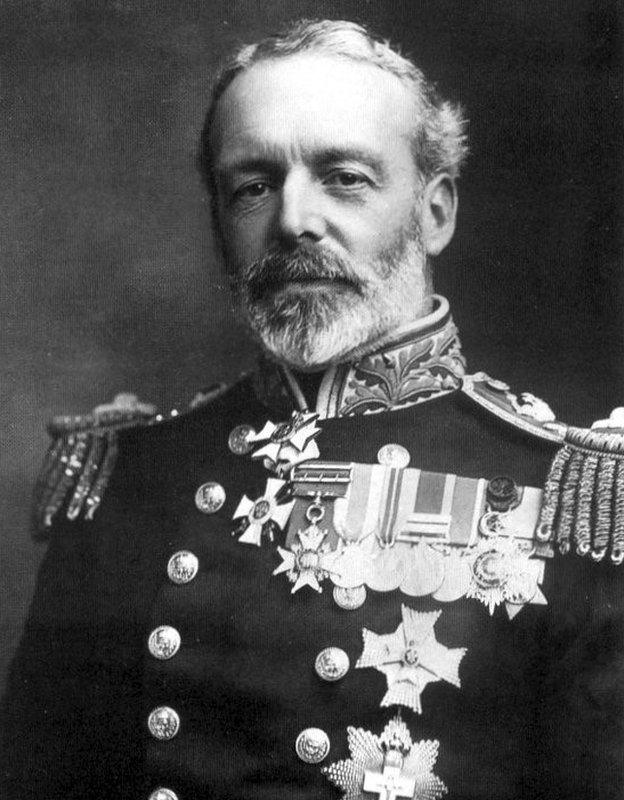

In contrast, the British squadron, led by Rear-Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock, was outdated.

"The ships were old. The two armoured cruisers were badly designed. All the odds were stacked against them," Hewitt said.

Rear-Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock perished when HMS Good Hope was sunk

"Cradock was in a difficult situation. He was going up against serious opposition, he knew his force was inadequate and to make matters worse he was getting bad direction from London."

The battle started in the late afternoon and went on into the night. It was clearly visible from the shoreline of Chile, which remained neutral throughout World War One.

HMS Good Hope was the first British ship to sink, taking Cradock with it.

Just over an hour later, the Germans sank HMS Monmouth with the loss of all hands.

After their victory, the Germans sailed northwards and docked at the Chilean port of Valparaiso, where they were feted as heroes by the large local German community.

But von Spee, it seems, was in no mood to celebrate.

He had used much of his ammunition at Coronel and was far from home, with few options to refuel.

And he was expecting a British backlash.

When given a bouquet of flowers in Chile he reportedly said: "These will do nicely for my grave."

Just over a month later he was dead, one of the hundreds of German victims at the Battle of the Falkland Islands.

- Published1 November 2014

- Published5 August 2014