Mexico missing students: Looking for Iguala mass graves

- Published

The people of Iguala have been living in fear knowing the mass graves existed, say relatives

The group is small. No more than 40 people, celebrating mass in the middle of a dusty road on the slopes of Guerrero, Mexico's only state to be named after a former president.

At the end of the ceremony, they start saying names out loud: "Hugo Bailon Sanchez. Protect him, Lord."

"Juan Alberto Bautista. Protect him, Lord."

More than 30 names are read out - belonging to missing brothers, husbands, wives and sons.

Names of people the group is looking for in the rocky mountains around Iguala. Possibly in mass graves.

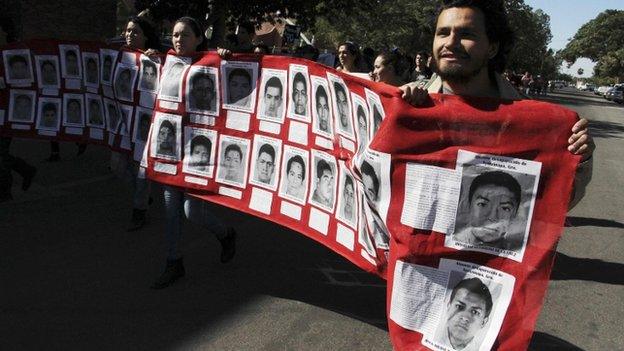

Voicing outrage - protesters demand justice for the 43 students missing since clashes in September

The disappearance - and alleged killing - of 43 students in the town of Iguala in late September has caused outrage in Mexico and around the world.

According to some Mexicans, it is the tip of the iceberg.

In the weeks since the students disappeared, at least 300 families have come forward claiming they too have relatives missing in the area.

Some of them have waited in silence for years for loved ones to return.

Inspired by the media - and government - attention that the case has received, they have been conducting their own search for missing family members.

"I"ll search to find you" - the message printed on T-shirts worn by people searching for their missing relatives

However, many relatives at the mass are too afraid to speak.

One of them is Jorge Popoca.

In August, his wife and their three children - the oldest of whom is four years old and the youngest 15 months - were kidnapped in Iguala.

Despite paying a ransom, he has not heard from them since.

During the mass Mr Popoca cannot stop crying long enough to utter any of their names.

Afterwards, however, he gathers the strength to tell his story.

"We knew about the mass graves, but not how big the problem was. The authorities never did anything. And people were too afraid to act. The population of Iguala lived in fear. They knew that the police were involved."

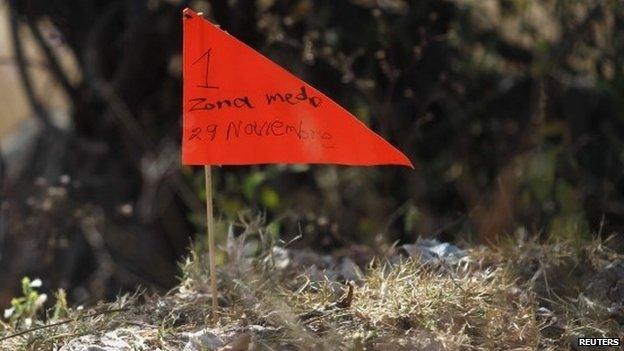

The search took relatives back to the area where authorities were said to have discovered mass graves in October

Prayers were said before relatives continued searching for remains of their loved ones

Flags were planted where relatives think clues of more missing human remains may be hidden

Reign of terror

The people of Iguala have been enduring a reign of terror for two years, locals say.

Mexico's Attorney General Jesus Murillo Karam found evidence that Jose Luis Abarca, the arrested former mayor of Iguala, and his wife were working with the Guerreros Unidos (United Warriors) drug gang.

Several local police officers were also on the payroll of the criminal organisation, and dozens were believed to be involved in the kidnapping and alleged murder of the students.

All of this went unnoticed by the authorities.

"Many of those crimes require a complaint to be investigated. It is true that in Guerrero, in the last 10 years many of these crimes weren't reported because of fear. Sometimes fear that the police were involved", explains David Cienfuegos, Guerrero state's newly appointed interior minister.

"In places like Iguala, criminal groups have not only infiltrated the police, but also the political class. There has been talk of 'narco-politics'," he says.

There could be a similar situation in many more isolated towns in Guerrero than Iguala, added Mr Cienfuegos.

Meanwhile, in the hills of Iguala, the search continues.

Split into small groups armed with shovels and pick axes, family members are prodding the ground, trying to identify areas big enough to hide a grave.

Whenever they find anything suspicious, they mark the spot with a small flag, so experts can come and dig there.

It is a thankless task, which many of them have been doing for months.

Maria del Carmen Abarca Baena, whose husband Saturno Diaz Beltran would be turning 48, described his disappearance in March.

"He left the house in the morning to go to a class - he was studying for a law degree. But he never came home," she said.

"I don't know what happened to him - I don't believe anything - the only thing I know is that I'm looking for him, and I pray to God that I find him."

Like many relatives, Maria does not expect justice for her missing loved one.

She just hopes to find his remains and give him the dignity of a final resting place, not just a hole in the ground of these hard, unforgiving hills.

- Published2 December 2014

- Published20 November 2014

- Published8 November 2014

- Published4 November 2014