Families of Mexico's missing students refuse to give up

- Published

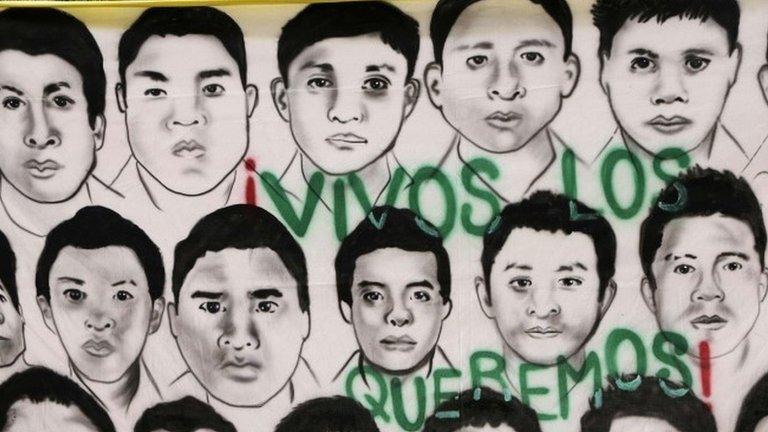

The disappearance of the 43 students from a college in Ayotzinapa has shocked Mexicans

It has been more than four months since 43 students from a rural teaching school in Ayotzinapa, in Mexico's south-western state of Guerrero disappeared.

They were last seen alive during a protest in the town of Iguala.

Police fired on them and rounded them up, eventually handing them over to members of the Guerreros Unidos drug gang, who are widely thought to have killed them.

But the students' families refuse to believe they are dead. They say they want more answers and will not give up looking for them.

So how can Mexico move on?

Clamour for justice

Last week Lourdes Caballero Sanchez took to the streets of the capital with thousands of other Mexicans to call for justice.

Lourdes Caballero Sanchez says she thinks her brother Israel is still alive

It was a personal journey for her. Lourdes's 21-year-old brother Israel is one of the missing.

Her belief that she will find him is unwavering.

"I have an intuition that he's still alive. That's why we are here, asking [President] Pena Nieto to give us back our boys," she told me.

"As a sister, I'm desperate. I miss him, I want to see him. I feel so powerless to not be able to do anything for him."

Officially dead

But less than 24 hours later, Mexico's Attorney General Jesus Murillo Karam delivered a blow.

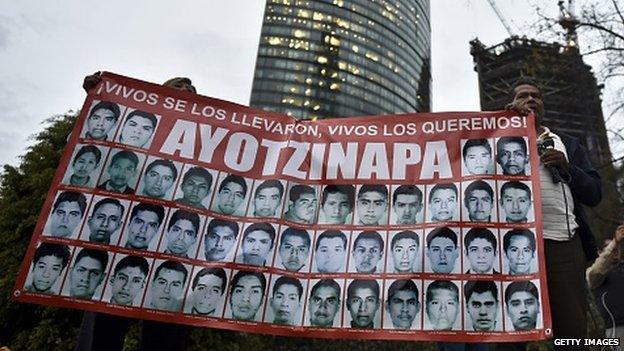

Demonstrators have made it very clear they "don't believe" the government

He declared that the students were dead.

His team, he said, had interviewed 99 people including members of the criminal gang that he alleges murdered the students.

Based on 386 declarations from interviewees, 16 police raids and two reconstructions, the conclusion was that the students were killed by the gang and their bodies burned at a rubbish dump.

The students' families angrily rejected this scenario.

At a press conference held later in the day, one mother stood up and claimed that her son was not missing, he was being held by the government.

Accusations that the government needs to be called to account have been flying at the same time that the authorities have been trying to draw this questioning to a close.

The prosecutor reassured the families the case would not be shut yet, but even President Enrique Pena Nieto has said Mexico needs to move on.

Clinging on to hope

For many though, that is not an option.

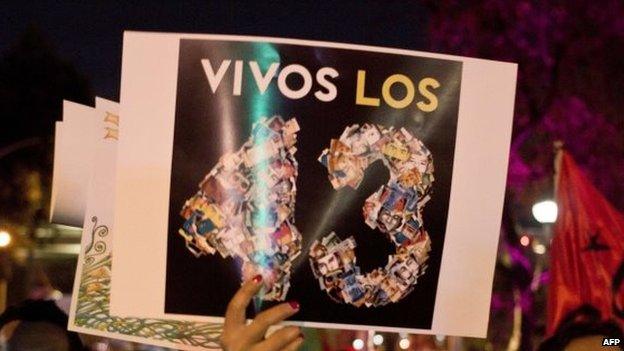

The relatives refuse to believe the 43 are dead and say they will not give up their search

"I can understand the political logic of trying to put this behind the country, but I don't think there are the objective conditions for the country to turn the page," says independent security analyst Alejandro Hope.

"The government has provided a narrative of what happened but hasn't yet provided an explanation. In the absence of a detailed version of why, this case will not be closed."

The war on drugs has taken a brutal toll on Mexico in the past decade.

More than 100,000 people have been killed and the latest official figures put the number of missing at 23,271.

Many Mexicans are not satisfied with the official account given of the students' disappearance

This week, some of the parents of the missing students travelled to Geneva to appeal for help from the United Nations Committee on Enforced Disappearances.

Mexico's National Human Rights Commission also published a report ahead of the visit.

Commission President Luis Raul Gonzalez Perez criticised the impunity in Mexican society, which he believes dates back to the 1970s and 1980s: decades when the government and left-wing student groups clashed with deadly results.

He gave several recommendations to be discussed at the UN's sessions, one of which was a more systematic database of the missing to understand the true extent of the problem.

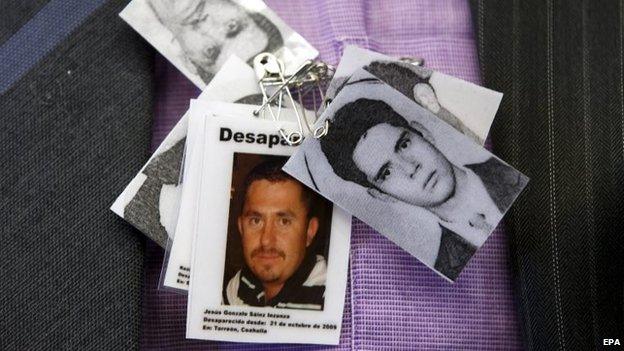

Enforced disappearances

One of the big concerns among human rights groups is that although many of the suspects arrested have been charged with kidnapping and murder, none have been charged with the crime of enforced disappearance.

Enforced disappearances are not a new phenomenon in Mexico

"It reflects that the Mexican government is reluctant to recognise that in Mexico enforced disappearances occur," says Denise Gonzalez, of the Miguel Agustin ProJuarez Human Rights Centre.

"They are trying to water down their responsibilities. They are reluctant to recognise that state officials have engaged in enforced disappearances in Mexico."

In a country used to the high number of dead in the drug war, this case of the Ayotzinapa students has stood out.

The feeling, say experts, is that these young men should not be viewed as collateral in a narco-war.

It has forced people to push for change.

"The majority of Mexicans are now empowered and feel a personal responsibility to change things in the country," says John M Ackerman, a law professor at Mexico's National Autonomous University.

"This is an invaluable achievement since it implies an historic break with the learned pessimism and passivity encouraged daily on the principal television and radio networks in Mexico."

Changes ahead?

Their disappearance has forced the government to make changes, too.

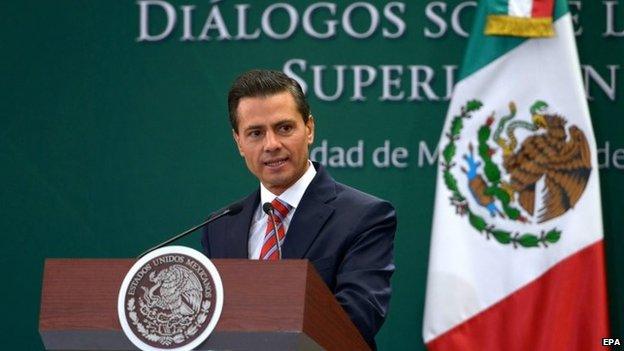

In November, President Pena Nieto announced plans to put all local police units under federal control and allow Congress to dissolve local governments infiltrated by drugs gangs.

President Enrique Pena Nieto has promised to reform the police forces in the wake of the disappearances

But with mid-term elections later this year, there are question marks as to whether these sweeping announcements will all get voted in.

"It was a watershed moment for Mexican society, maybe," says Alejandro Hope. "But a watershed moment for government policy? I don't think so."

Despite the feeling of stalemate among many, the investigation is not over yet.

The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) signed an agreement in November with the Mexican government and representatives of the disappeared students to look into the events of Ayotzinapa.

They will be holding their first meeting later this month.

There are still many questions surrounding the students' disappearance.

The hope is that perhaps the IACHR will provide some answers to try and prevent another Ayotzinapa from ever happening again.

- Published4 December 2014

- Published20 November 2014

- Published13 November 2014