Mexico missing students: Fear and distrust six months on

- Published

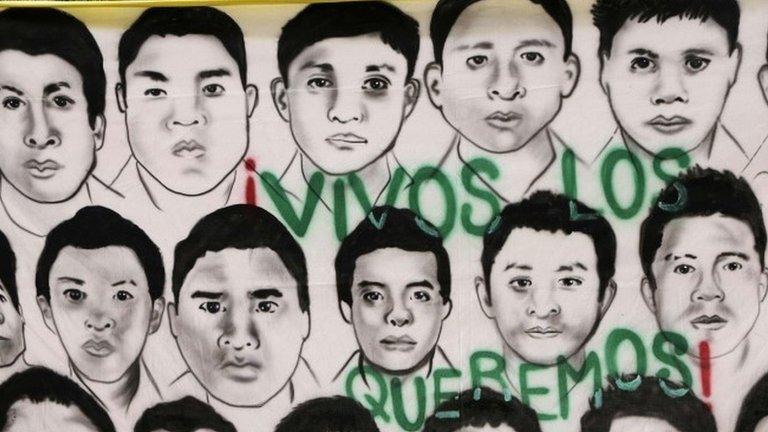

The college in Ayotzinapa is now a shrine to the missing students

It is six months since 43 students went missing in the Mexican state of Guerrero. They disappeared after clashes with police in the town of Iguala.

The government says the students were handed over to drugs gangs by corrupt local police - but the parents refuse to accept this and are demanding more action to find their loved ones.

It is a sunny afternoon in the Raul Isidro Burgos rural teachers' college in Ayotzinapa. The warmth has brought out a chorus of chirping birds, and some young children are kicking a ball about on the grass.

In the centre of the college, a few people are on the basketball court. This would normally be the heart of the college, a place where people would come and relax.

Now it is a shrine to the missing. At one end, there are 43 desks - each one with a picture of a student.

A college shirt is draped over the back of one of the chairs; other people have left balloons, pictures and trinkets.

Without knowing where their sons and brothers are, nor being able to bury them, this feels like the closest the families can get to visiting their loved ones' graves.

'World has forgotten us'

On the other side of the basketball court Erica de la Cruz Pascual is cradling her three-year-old daughter Alison. Erica's husband, Adan Abrahan, is one of the missing.

Erica de la Cruz Pascual says her young children are suffering without their father

Every day she comes here with her little girl and eight-year-old son Jose Angel, hoping that one day he will walk back through the college gates. It is her son who has taken it the hardest.

"At first, we didn't want to tell him, but we have to be honest. He's been really sad ever since," says Erica. "He doesn't want to leave here, he says he wants to be a teacher like his dad."

Nearby, I meet Floriberto Cruz, whose grandson Jorge Anibal is also missing. President Pena Nieto has said that it is time to move on, but the families disagree.

"Sometimes we think the world's forgotten us because we don't get any support," Floriberto tells me. "We know that people from around the world know what happened here but we have no way of knowing if they're supporting us."

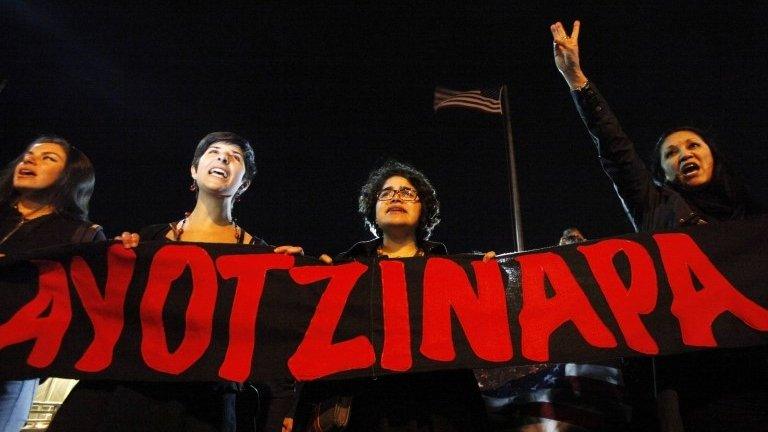

The case of the 43 students galvanised Mexican society - it was the sheer number that disappeared in one night that shocked many.

But they were not the first and nor were they the last to go missing in Iguala, the town that has become the centre of the horror story.

'Tense calm'

The journey from Ayotzinapa to Iguala takes about 90 minutes.

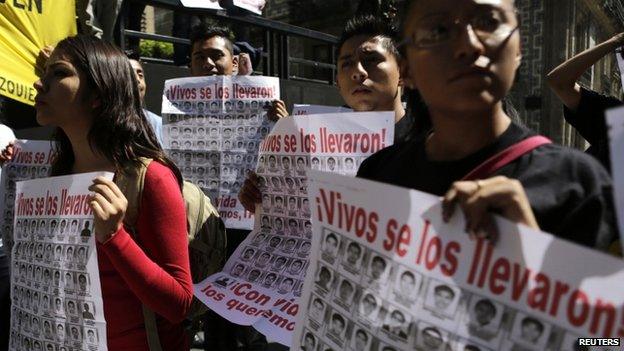

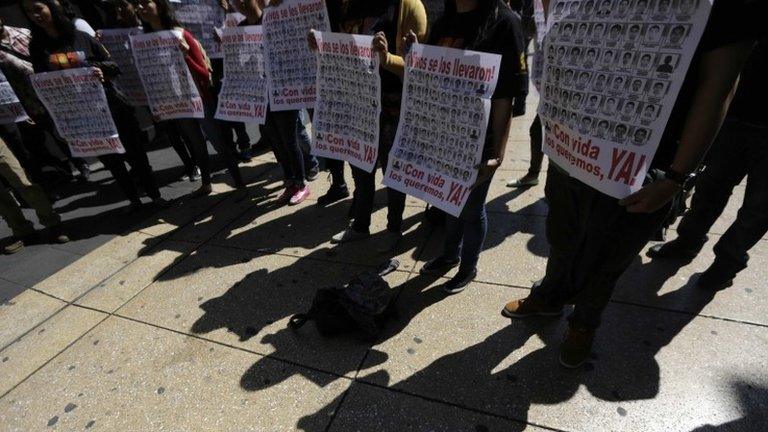

Thousands of people have been taken part in marches for the missing students in Mexico

I was warned about Iguala before I went. Some people call it an "infierno". Others just label it "caliente" (or "hot') - in reference to its violent reputation.

One man stopped me in the street in the centre of Iguala to talk. I asked him how it felt to him. "Calma-chicha," he called it, explaining that there was a sort of "tense calm" in the town.

Iguala is at the heart of Mexico's opium trade. Surrounded by mountains where poppies are to produce opium paste, the town is an important point in the route to the United States.

Iguala seems like any ordinary town - there is a large square in the centre with a beautiful orange church. Shops around the square sell everything from Mexican ice lollies to boom box speakers that blare out mariachi music to everyone passing by.

But we were warned by many people to watch our backs. Halcones - or hawks in English - hang out on the street corners or drive by on motorcycles and radio their friends to let the criminal gangs know what is happening in town.

I spoke to several people, and when I asked whether they would talk to me as a journalist, the response was "it's complicated".

Distrust and boycott

But Jehuet was willing to tell me her story.

Last year, her younger brother, who was 25, was kidnapped after taking his son to nursery.

The family paid a ransom of 30,000 Mexican pesos ($1,980; £1,330) and he was released.

Then, eight weeks ago he was kidnapped again. This time, he was shot in the head execution-style and his body dumped in a poor neighbourhood. Paradoxically, she says her family was lucky.

"What's happening in our lives is so depressing, so brutal," she says.

"We used to have to thank God for another day of life, for our health, to be looked after. Now we have to thank the criminal gangs that we are alive. We have to thank them for allowing us to be with our families for just one more day.

"But we also have to thank them for giving us my brother's body because there are some people - those families of disappeared - who don't have their bodies or only parts of them."

In the wake of the students' disappearance, Iguala Mayor Jose Luis Abarca was arrested along with his wife, accused of ordering police to confront the students on the night they disappeared.

Few people here trust local politicians - the feeling is that Mr Abarca was just one of many corrupt mayors in office in Guerrero. There is now a growing movement to boycott elections in June.

Lethal mix

"Nothing has changed since the disappearance of the students," says Ezequiel Flores, the Guerrero correspondent for national magazine Proceso.

"The same political forces that encouraged that mayor are working with other people but with the same practices and the same links. In other words, mafias have won over the political parties."

In Guerrero's capital Chilpancingo, I meet a businessman who says he is different. Pioquinto Damian Hueta is running for mayor and knows first-hand about violence.

Last year, 180 bullets were fired into his car, killing his daughter-in-law and injuring his son. Mr Hueta believes he was the intended target. Despite this, he still wants to run for office.

"Yes, I'm scared but I'm more scared about staying silent," he says. "I'm more scared about doing nothing, about being a spectator and seeing my municipality come apart. Fear of being paralysed and doing nothing, watching Guerrero and how it's come undone."

The events of September turned the world's attention to the violence in Guerrero - but six months on, little has changed.

Life is hard for people who live here, especially in towns like Iguala.

After a while, it is hard to trust anyone you speak to. Everybody has a shocking story to tell and none of those stories are simple to understand.

Politics, drugs and violence - it is a lethal mix. And one that seems almost impossible to unravel.

- Published27 February 2015

- Published5 February 2015

- Published13 November 2014

- Published30 November 2014