Life in a Colombia village threatened by landmines

- Published

Natalio Cosoy reports from Anori where people live in fear of landmines

Colombia's government and left-wing Farc rebels recently agreed to clear the country of landmines as part of the ongoing peace talks. But the job could take decades. BBC Mundo's Natalio Cosoy visited one area where residents live in constant threat of being killed, maimed or injured.

On 1 December 2012 Jair de Jesus Arboleda was cleaning the area around his home in rural Colombia when he stepped on a landmine.

His house is located in an isolated part of Anori, a village in Antioquia, the province in the north-west of the country which holds the sad record of having the highest number of landmine accidents in the country.

Mr de Jesus Arboleda, 40, recalls how he had to crawl for two days to reach a road.

Jair de Jesus Arboleda had to have his leg amputated after stepping on a mine

There, he flagged down a lorry which took him to hospital.

But it was too late to save his right leg. It had to be amputated.

'Ashamed of his injuries'

Jhon Fredy Marin Zapata was herding cattle with his father in another part of Anori on 12 March.

At one point he lost his footing and when he put his left hand on the side of the path to regain his balance, he activated an explosive device.

The 17-year-old, who has a cognitive impairment, lost parts of two fingers and was injured by shrapnel in various parts of his body.

Jhon Fredy Marin Zapata was injured by an explosive device on his family's property

He is still shocked by the accident, and constantly hides his injured hand.

"It is like he is ashamed," says his mother, who found her son after hearing him screaming for her as he lay injured.

Ms Zapata says that while everyone knows there are landmines in Anori, she never imagined someone in her family would be injured, even less so on their land.

Official figures suggest some 160 people have been injured by explosive devices in Anori in the past 25 years.

In that same period, more than 11,000 people have suffered accidents with landmines and other explosive devices across Colombia, and some 20% of them died.

Curse of natural wealth

Currently Colombia is third in the list of countries with the most landmine accidents, behind Cambodia and Afghanistan.

Children, who often wander off well-trodden paths and pick up objects they find on the ground, commonly fall victim to the devices.

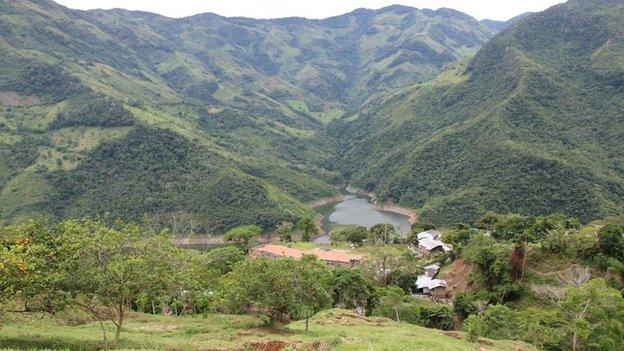

Anori is particularly badly affected because it not only has been the scene of clashes between the security forces and left-wing rebels, but is also an area where right-wing paramilitaries have been active.

The ground here is full of natural wealth that has become a curse, luring many of the illegal groups.

Its fertile soil is good for crops, including coca, the raw ingredient of cocaine.

The area around Anori is fertile and therefore valuable to illegal armed groups

Local prospectors have found gold in the area

Gold, too can be found, attracting illegal mining.

A hydroelectric dam on the River Porce is an attractive target for rebel groups seeking to disrupt the area's infrastructure.

Residents live with the constant threat that brings.

Mr de Jesus Arboleda had to abandon his property after he was told it was no longer safe.

"I cannot work [there] anymore, I cannot do anything," he says.

Improvised devices

Jhon Fredy's mother told me she now lives in fear her younger daughter, who is 10, may veer from the path on her way to school and walk into a minefield.

The explosive devices most commonly used by the illegal armed groups in the area are often improvised.

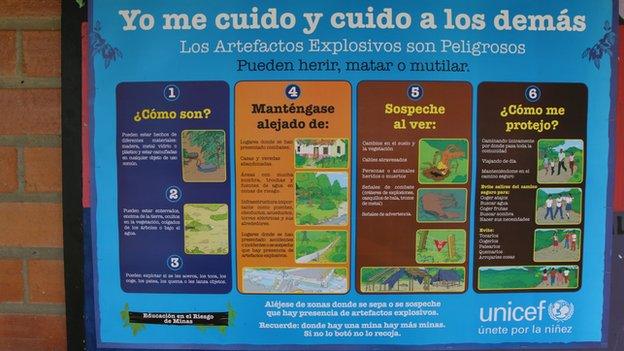

Posters have been put up to warn children of the dangers of explosive devices in the area

They are made out of plastic, glass and other materials that make them hard to detect.

Sometimes they are triggered by a passer-by picking up a tempting object, such as a mobile phone.

Local non-governmental organisations such as Corporacion Paz y Democracia (Peace and Democracy Group) use training materials provided by Unicef to educate youngsters about the dangers.

"There can also be a string, and if you step on it, it can trigger the explosion," primary school pupil Alejandra Quiroz Piedrahita tells me after attending a class.

The idea is that if children learn the information by heart they will be able to share it with the rest of their family and the wider community - and that other residents of Anori can avoid suffering the same fate as Mr de Jesus Arboleda and Jhon Fredy.

- Published14 March 2015

- Published15 December 2010

- Published24 September 2015