'El Chapo' Guzman: Sinaloa's saviour or sinner?

- Published

For the aspiring drug lord: Sinoloa souvenir sellers have begun to stock El Chapo merchandise

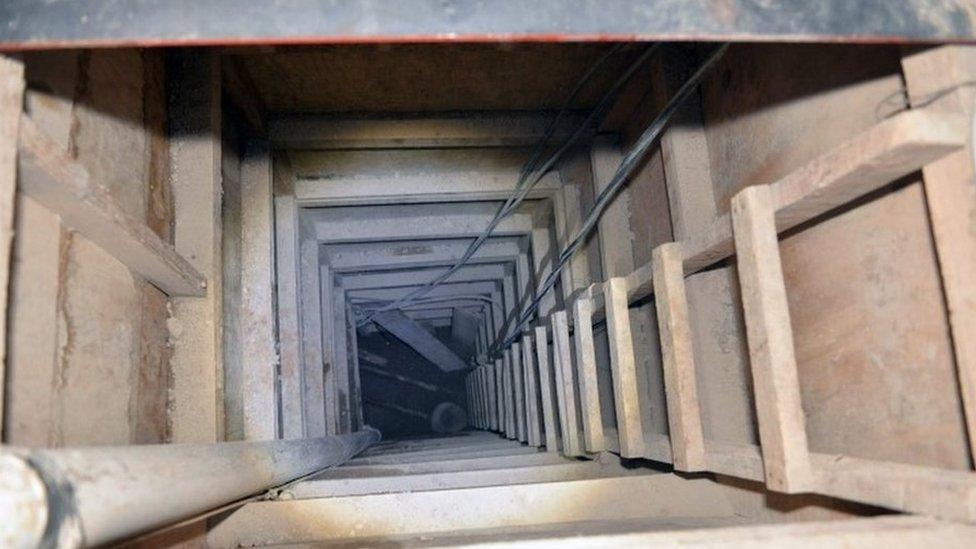

It is little over a month since one of the world's richest drug lords, Joaquin "El Chapo" Guzman escaped through an impressively built mile-long tunnel.

He is an elusive character, even to people in his home state of Sinaloa, the cradle of Mexico's drug-trafficking area. But while Sinaloans cannot hope to rival his riches, they have not wasted time cashing in on his fame either.

Isaiah Rodriguez has several stalls inside the labyrinthine Garmendia market in the historic centre of Culiacan. He mostly sells souvenirs and trinkets printed with "I LOVE CULIACAN" or "SINALOA".

But Isaiah has a new range out - a line of baseball caps branded with "El Chapo" - the word "billionaire" stamped on the front, along with a golden-threaded image of the kingpin and the number 701, referring to El Chapo's position the first time he entered the Forbes Rich List.

Isaiah says wholesalers started offering them to him shortly after El Chapo escaped.

"As a shop-seller, it's good business," he says. As an individual he has a very different view - "I wouldn't let my kids wear one of these hats."

Worshipping the underdog

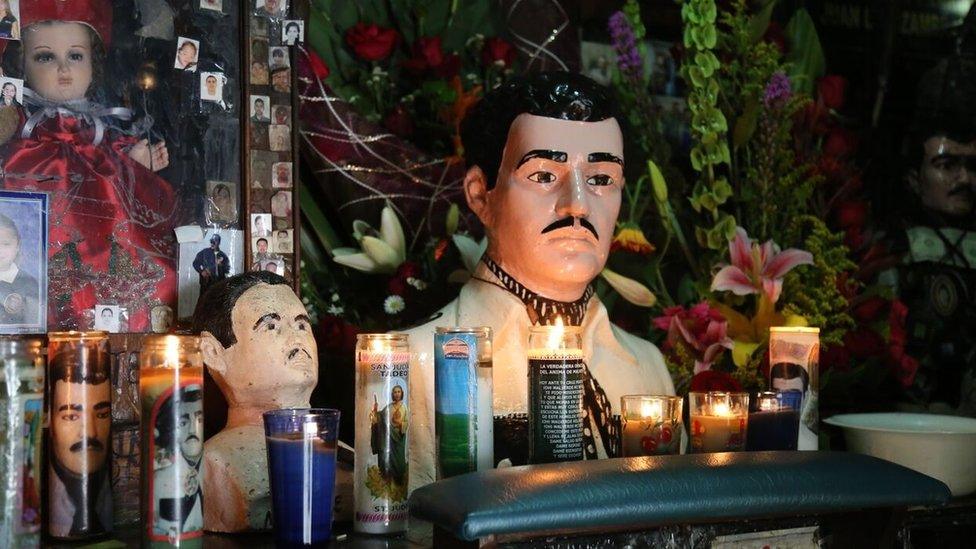

Not far away from the market is a little chapel dedicated to another of Sinaloa's famous bandits, Jesus Malverde. The chapel is dimly lit by candles and the walls are covered in plaques from families thanking Malverde for his work.

Legend has it that he robbed from the rich and gave to the poor, for which many people are still very grateful. He is known as the "angel of the poor" but he has another nickname too: the "narco-saint" - because of his following among the cartels.

Jesus Malverde, another famous Sinaloa bandit, has a chapel dedicated to him

Malverde is the original benevolent bandit, but he is has increasing competition.

"El Chapo has helped lots of people so it would be good to have a monument or a chapel in his honour too," says Rodolfo, who maintains Malverde's chapel. "He is also a generous man."

Modern day Robin Hood, or assassin?

The idea that El Chapo, the leader of one of the most powerful and violent drug cartels in the world, can be seen as a good guy is not uncommon here.

"There are parts of society that are proud," says Javier Valdez, a columnist on narco (drug dealer) culture for the weekly paper Rio Doce. "They talk of narcos as being awesome people, an idol or God or demi-God."

El Chapo is also seen as somebody who can offer more security to people than the government.

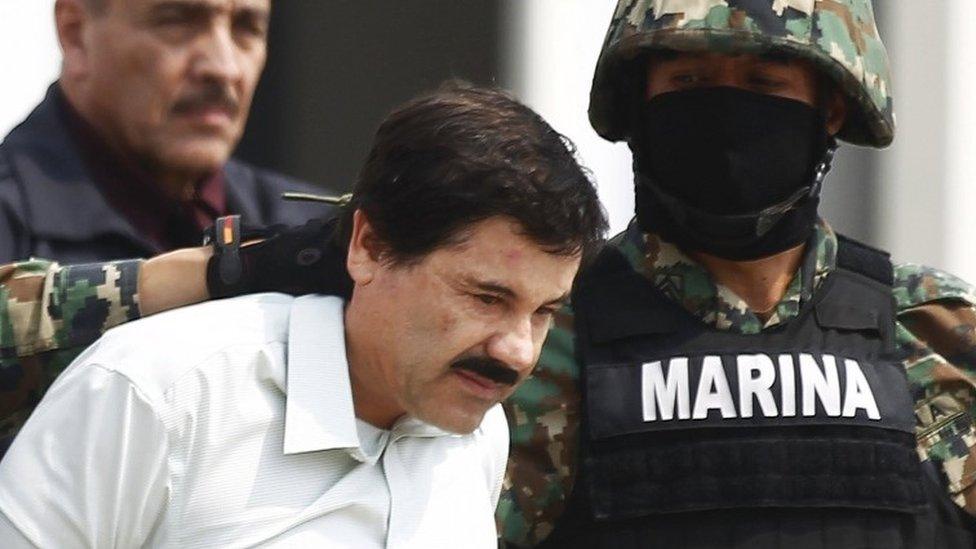

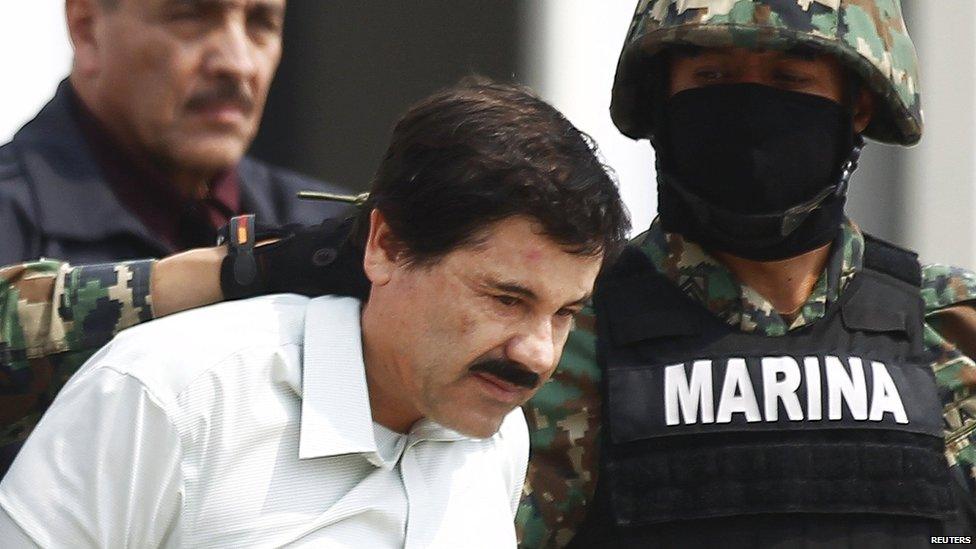

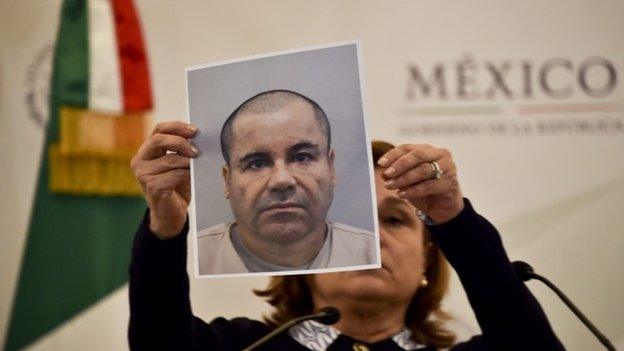

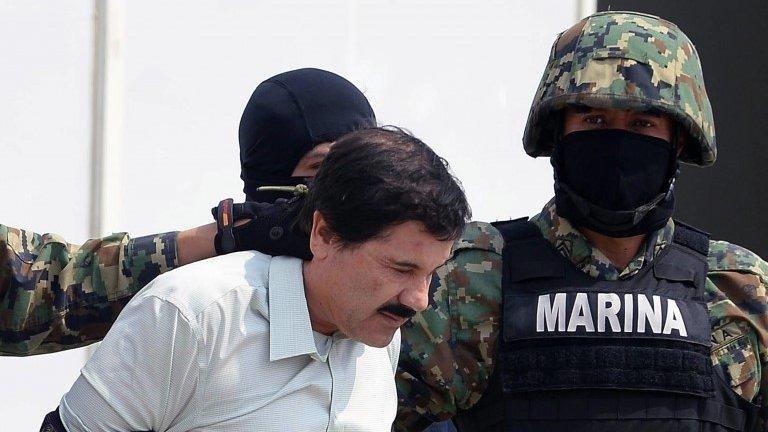

El Chapo was arrested in February 2014 but escaped through a tunnel in July this year

"He gives them work and money but more than that, he challenges the government, makes fun of the government, escapes from prison. He's a modern-day Robin Hood," says Mr Valdez.

But, he adds, it often means that El Chapo's darker side goes unacknowledged.

"People don't want to know anything about the kingpin they adore also being an assassin," he says. "They don't want to have anything to do with the painful side."

'El Chapo's the best'

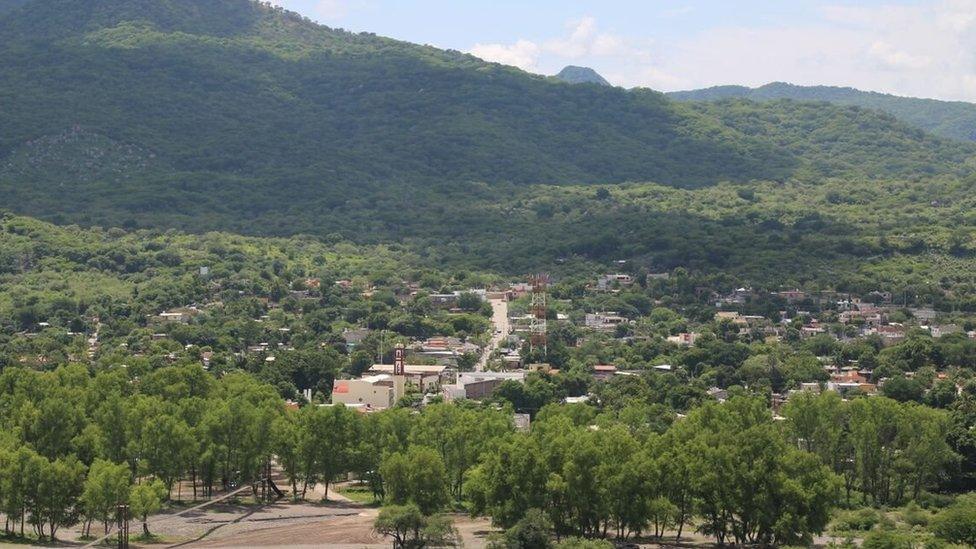

Travel an hour into the Sierra Madre mountains and you get to the municipality of Badiraguato. Not far from here was where El Chapo grew up and where his mother still lives.

This is one of the biggest areas in Mexico for opium and marijuana production. It is also where many think El Chapo is hiding.

"El Chapo's the best," says Simona, who runs a restaurant in town. Her father used to cook for Rafael Caro Quintero, another of Badiraguato's famous drug-traffickers.

She is happy for what El Chapo has achieved in a poor part of Mexico where there are few job opportunities apart from agriculture. "Drugs traffickers are real men," she laughs.

But in the town hall, Mayor Mario Valenzuela is a little more measured. He knows El Chapo's mother and while not exactly proud of his crimes, Mr Valenzuela says the production of drugs in this part of Mexico is reality.

"He's a person who, in his line of business, is very intelligent," he says. He jokes that, with his escapes, El Chapo could be in line to win a Guinness World Record.

"It's complicated but at the end of the day it generates jobs in the country, it moves money - and a lot of it," he says. "We don't want to face up to the fact that our economies to a large extent depend on that. Sadly that's how it is."

Some suspect El Chapo may be hiding around Badiraguato, near where he grew up

Mr Valenzuela says rumours that El Chapo has ploughed money back into his community are untrue. There are no bridges, roads or buildings here that can be attributed to the drugs lord, he says.

Guadalupe, 15, who is sitting in the square outside the town hall, disagrees with the mayor.

"I know it's true, he does help lots of people," she says, adding that she thinks he is a good man.

A tomb fit for a kingpin

Back in Culiacan, I head to the Jardines del Humaya private cemetery, where many cartel members are buried.

The tombs are not your typical gravestones, they are actual houses. It is like a leafy neighbourhood where nobody is home. There are colonial-style buildings with two floors and gardens, more modern constructions too with marble staircases and alarm systems. Some even have air conditioning.

The builders are busy working on the next mini-mansion. They do not ask questions about their clients but say that even if they are building for drug dealers, everyone deserves to rest in peace.

And whether he returns to prison or remains on the run, a drug dealer of El Chapo's stature can be assured of a very luxurious resting place indeed.

- Published20 July 2015

- Published15 July 2015

- Published14 July 2015

- Published13 July 2015

- Published12 July 2015