US 'will not press for Farc extraditions' from Colombia

- Published

An agreement on transitional justice reached on 23 September was seen as breakthrough

The US ambassador to Bogota says the US will leave it up to Colombia to decide how to deal with demobilised Farc rebels who have committed crimes.

Ambassador Kevin Whitaker said the US would not press for the extradition of left-wing Farc guerrillas.

A number of Farc rebels have in the past been extradited to the US to serve long sentences for drug trafficking.

The Farc and the Colombian government are engaged in peace talks and recently reached a deal on transitional justice.

'Historic agreement'

Speaking to Colombia's Caracol Radio, Ambassador Whitaker said the agreement the Colombian government and rebel negotiators had reached on 23 September was "historic".

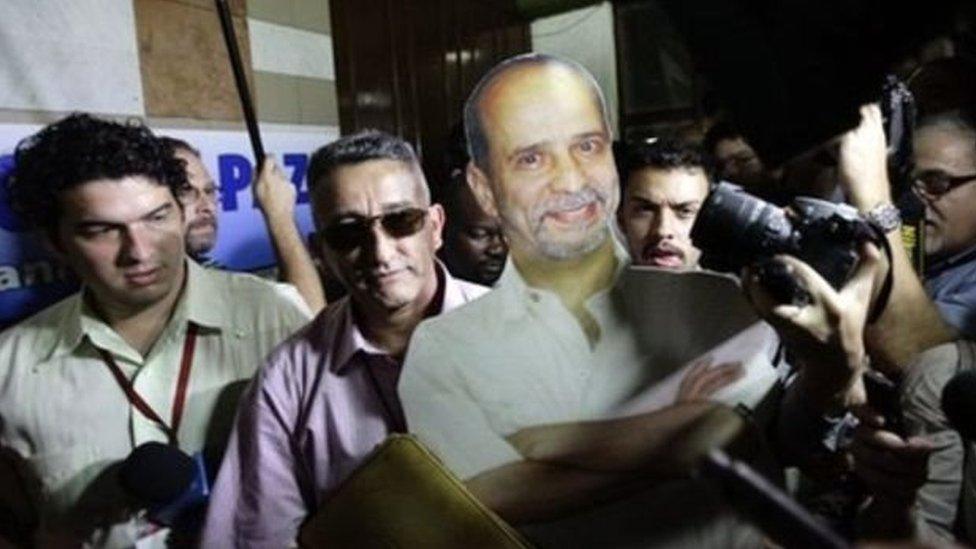

Farc rebels carried a cardboard cut-out of Simon Trinidad to the negotiations in 2012 to push for his release

Under the deal, rebels who have committed political crimes as part of the conflict will be granted an amnesty.

Only those who refuse to own up to crimes committed will be sent to ordinary prisons while the others will undergo "alternative forms" of punishment.

Farc negotiators have in the past said they would not accept any agreement which could see their members deported to the United States,

They have also been pushing for the release of the senior Farc rebel known as Simon Trinidad from US custody.

Trinidad, a senior Farc rebel, was deported from Colombia to the US, where he was sentenced to 60 years in prison for plotting to hold three Americans hostage.

'Friends and allies'

Ambassador Whitaker said on Tuesday that US justice authorities would always seek those suspected of crimes.

"But if the [Colombian] government decides it is not convenient to extradite them [to the US], we'll respect that."

"If you want to see that as the US's contribution to the peace process, you're welcome to do so," he added.

According to Mr Whitaker, some 2,000 Colombians have been extradited to the US since 2002, when an extradition agreement came into force.

The possible extradition of demobilised Farc rebels to the US was seen by analysts as a potential stumbling block on the road to peace.

"We're friends and allies and if we can help in this way, we will," Ambassador Whitaker said.

Thorny issue

The agreement on transitional justice between the Farc and the Colombian government is seen as a major breakthrough in the peace negotiations which started in November 2012.

The relatives of victims of forced disappearances demand to know what happened to their loved ones

The negotiations are currently continuing in the Cuban capital, Havana.

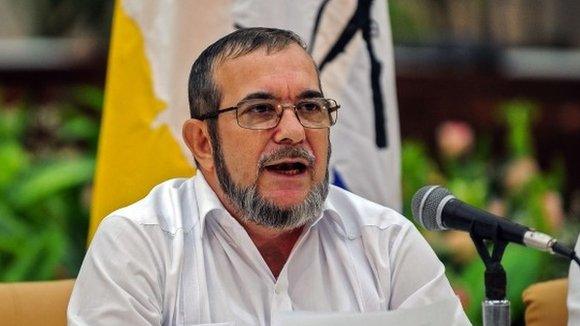

On Tuesday, Farc leader Timochenko tweeted, external that he hoped that by the end of the week there would be "an agreement on the disappeared which will fulfil the expectations of all the victims of the conflict".

An estimated 220,000 people have been killed in Colombia since the conflict began in 1964.

Many bodies have never been located and it has been a key demand by victims' groups that the Farc reveal the location of mass graves.

The justice deal at a glance

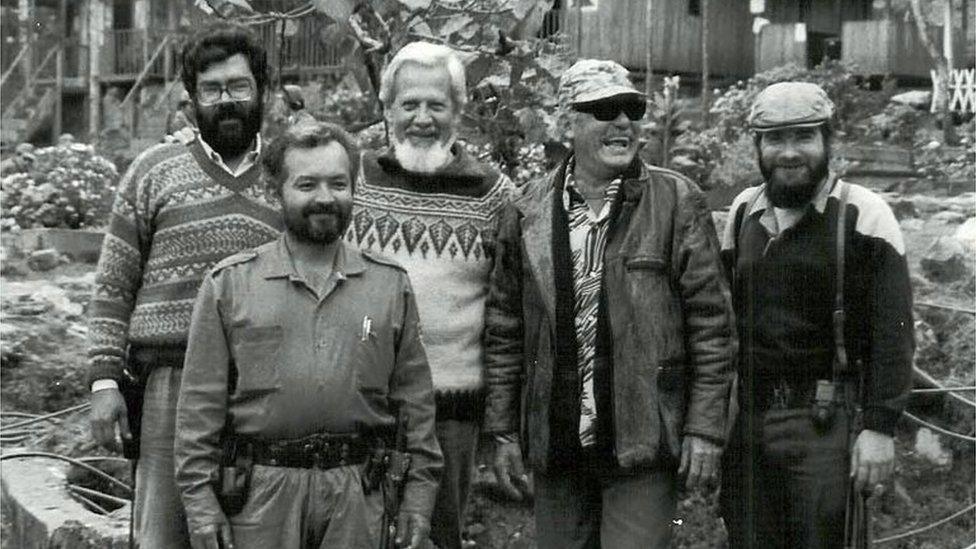

The Farc leadership has been fighting the government from the mountains of Colombia for decades

Who will mete out justice?

Special courts and a peace tribunal will be set up to deal with alleged crimes related to the conflict and will try all participants in the conflict, including members of the security forces.

Will there be an amnesty?

Yes and no. Combatants will be covered by an amnesty, but war crimes and crimes against humanity will not fall under it.

Will Farc leaders be sent to jail?

That depends. Those who confess to the most serious crimes will see their "freedom restricted" and be confined, but not in ordinary jails. It is not yet clear where they would serve their sentence instead. Those who confess past a certain deadline or refuse to admit their crimes altogether will go to prison for up to 20 years.

Will the guilty pay for their crimes?

Even those who will not be sent to prison will have to carry out work aimed at repairing some of the damage caused in more than 50 years of conflict, such as helping to clear landmines and plant alternative crops where coca was grown.

- Published24 September 2015

- Published24 September 2015

- Published31 October 2014