Argentina polls: A tale of two women voters

- Published

Voters will have to choose between Daniel Scioli (left) and Mauricio Macri in the run-off vote on Sunday

Argentines will go to the polls on Sunday to choose a new president in a run-off election. The two candidates who came out strongest in the first round four weeks ago are Daniel Scioli and Mauricio Macri. The BBC's South America business correspondent, Daniel Gallas, spoke to supporters of each candidate to get a sense of what they feel the priorities of the new government should be in South America's second-largest economy.

Villa Soldati is one of the poorest and most violent neighbourhoods of Buenos Aires.

This part of the Argentine capital is a stronghold of Kirchnerismo - the political movement which came to the fore after Nestor Kirchner was elected president in 2003.

Community leader Rosa Ortega belongs to La Campora, a group of staunch Kirchneristas, as the supporters of the late President Kirchner and his wife and successor in office, Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner, are called.

Rosa Ortega is a community leader in Villa Soldati

Whatever happens on Sunday, the Kirchner era will come to an end.

Under Argentina's constitution, presidents can only serve two consecutive terms, so Ms Fernandez will not be able to run for the top job this time.

Her hand-picked successor is Daniel Scioli, and Ms Ortega tells me Villa Soldati residents overwhelmingly voted for him in the first round.

She says that people are afraid that if he does not win, social programmes for the poor brought in during the Kirchner era could be cut.

Before 2003, most people here relied on the Church for help, she explains.

"In the old days, we didn't have any social help. It was every man for himself," she says.

"The Church was the only one which took care of us, providing medication, food and used clothes for our children.

"But after Kirchnerismo started, things changed. Now the state takes care of us," she adds.

State help

It is early morning on a weekday and the busiest part of Villa Soldati is a local centre run by Anses, Argentina's social security department.

Banners in Villa Soldati express support for ex-President Kirchner and President Cristina Fernandez as well as the late Venezuelan leader, Hugo Chavez

The small room is full of young mothers and their babies. There are pictures of President Fernandez everywhere.

Anses provides a host of social programmes for the poor.

Low-income mothers can get about 700 pesos monthly ($72; £47) per child in child support.

College students are also entitled to a monthly payment so that do not have to work full time and can concentrate on their studies.

Ms Ortega tells me that in the past years, the local Anses office helped virtually all elderly people in Villa Soldati register with the state pension system.

Most had not been getting pensions because they had spent their entire lives working in the informal sector. Now each retiree gets about 3,000 pesos a month.

One-woman inflation index

In another part of town, I meet someone with very different views on the election.

Lawmaker Patricia Bullrich campaigns for opposition candidate Mauricio Macri.

Patricia Bullrich was one of the lawmakers behind the move to publish independent inflation figures

Ms Bullrich has the strange distinction of having had an inflation index named after her.

The "Patricia Bullrich Inflation" was born in 2011 in response to government inflation figures which were widely discredited by the markets.

Despite sharp price rises, the official inflation figures stayed relatively low.

Independent economists accused Ms Fernandez's government of trying to mask the real numbers by changing the methods used to calculate inflation.

They cried foul and released their own data. But Argentina's government went after them in the courts.

So Ms Bullrich and a few fellow lawmakers stepped in and used their parliamentary privilege to release inflation figures without risk of prosecution.

Their data became known as Congress Inflation Numbers - commonly referred to as "Patricia Bullrich Inflation".

Wide gap

The discrepancies between the official figures and theirs are huge.

Argentina's official statistics body Indec says prices rose by 11.9% from January until October of this year, while the "Patricia Bullrich Inflation" for the period is 25%.

Argentina's high inflation rate is widely blamed on currency controls adopted in 2011.

Argentina adopted currency controls in 2011

The move, intended to stem the flow of capital out of Argentina, made importing goods expensive.

That in turn pushed up the prices of everything from dollars to Argentine-produced goods containing imported components.

'No growth'

Ms Bullrich is adamant that Argentina's new leader will have to put an end to Kirchnerist policies.

"When we began with this policy, we didn't grow anymore", she tells me.

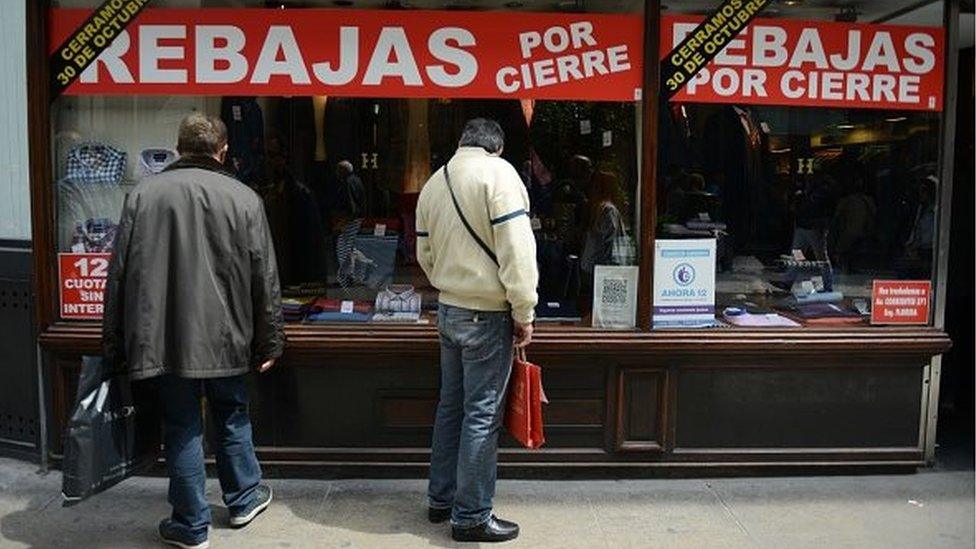

Some shops have been forced to close as the economy has suffered

"When the government started controlling dollars, they cut off all chances for our industry, country and agriculture to expand. For four years now we have not been growing. We are on ground zero."

Whoever is sworn in as president on 10 December will have a lot on his plate.

He will have to set a new credible policy for the currency that convinces foreign investors to come to Argentina.

He will also have to find a way to get Argentina back on international bond markets after its messy 2001 default.

And he will have to keep all the gains made by Kirchnerite social programmes.

Another task - possibly the hardest of all - will be to unify people who are currently very much divided about what to make of the Kirchner era.

- Published16 November 2015

- Published19 November 2015