Venezuela elections: Why did Maduro's Socialists lose?

- Published

President Maduro's Socialist party lost control of Congress for the first time in 16 years

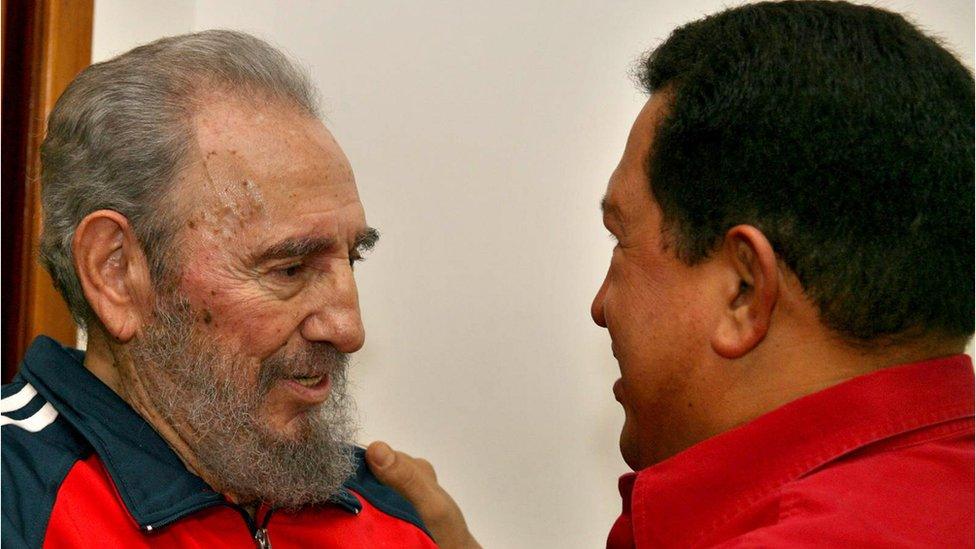

Hugo Chavez was the Fidel Castro of recent times - the two men were close friends, with the younger leader often travelling to Cuba for the kind of advice and counsel he was unlikely to find elsewhere.

But the Venezuelan military man-turned president took his mentor's ideology and reasoning one step further.

He could achieve a popular socialist revolution through the ballot box and keep repeating the process.

It was a lesson in democracy that frustrated the heck out of his ideological opponents in the region and made him a darling of left-wingers around the world.

Hugo Chavez's dream

Sunday's congressional election in Venezuela was meant to be another step on the country's journey towards President Chavez's dream of becoming the perfect socialist utopia.

But several things went wrong.

First of all, Hugo Chavez died almost three years ago after a long battle with cancer.

His successor, Nicolas Maduro, did not have the same academic qualifications, charisma or crucial connection to Venezuela's armed forces.

Secondly, the high oil prices that helped to pay for President Chavez's welfare programmes did not last.

Fidel Castro (left) and Hugo Chavez (right) were close friends - with the former giving Chavez advice

Despite having some of the largest oil reserves in the world, the country's profits forecast had to be radically reassessed when the cost of oil plummeted from over $140 to less than $40 a barrel.

Nicolas Maduro still enjoyed the support of the party faithful and Venezuela's working classes who had benefited from the Socialist Party's giveaways.

But others in the wider Venezuelan society were no longer unquestioning.

Some on the left despised the corruption that was allowed to proliferate as, after 16 years, the PSUV (United Socialist Party of Venezuela) began to believe too much in its own invincibility.

Facing an opposition alliance that now presented a united front, the governing party must have known it was in trouble.

Too little, too late

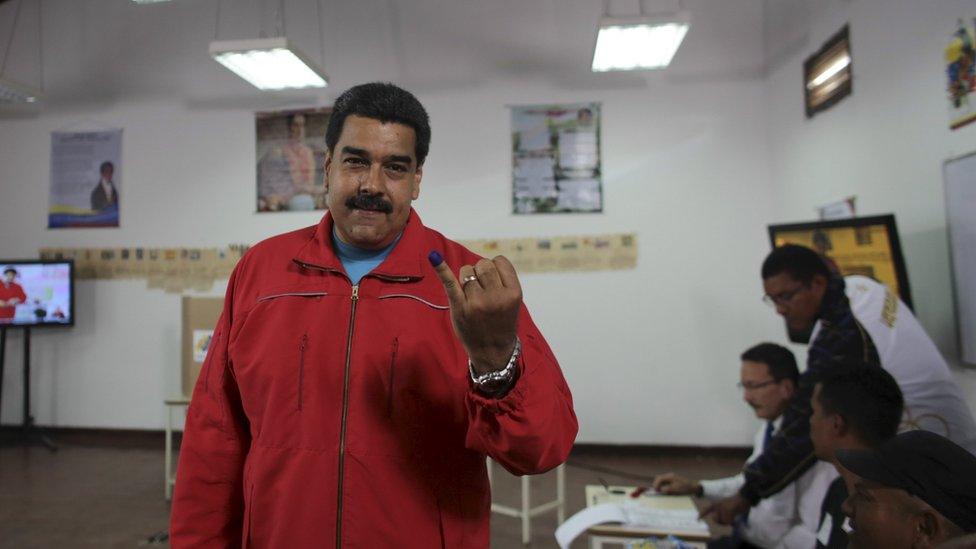

To its credit, Venezuela's electronic voting system is still one of the most efficient and transparent in the region and until the last hour of voting there were precious few irregularities.

It was only in an extended hour of voting that it became apparent the governing party was cajoling and persuading its supporters into the polling booths.

There were also allegations of voters in some instances being forcibly taken to the voting stations.

Too little, too late.

Voter turnout was reported to be over 70%

After years of political setbacks and infighting, the broad opposition coalition says it is up to the challenge of running the National Assembly.

Senior coalition strategist and veteran opposition politician Julio Borges told me what their legislative priorities would now be.

"Our chief aim is to promote a bill of rights so we can begin the process of releasing political prisoners," he said.

"Secondly, to push the government to take measures to improve the economy."

No quick fix

But that, of course, does not mean anything in Venezuela is going to improve overnight.

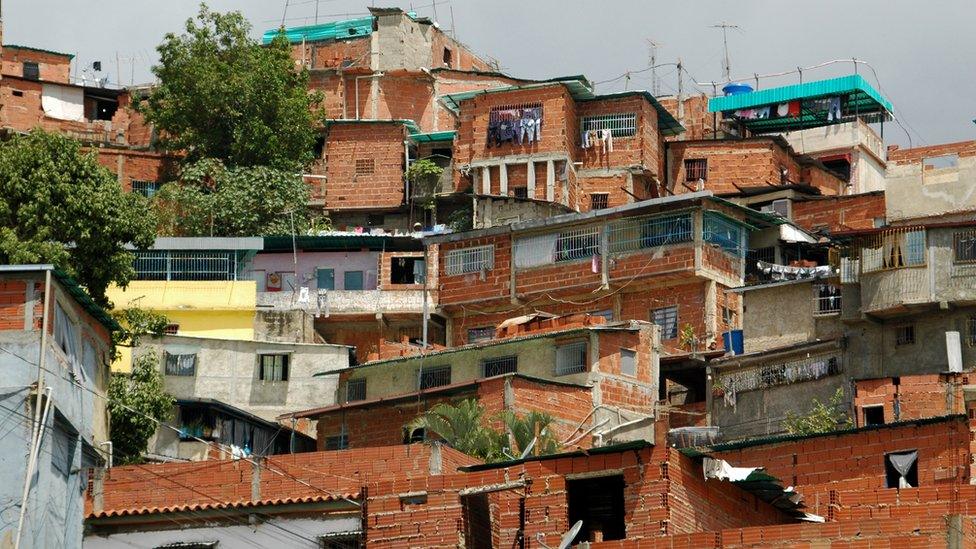

There will still be queues outside the supermarkets for basic goods on the day in January when the new legislators take their seats in Congress.

The streets of Caracas will still be too dangerous to walk after dark, and the same cupboards will still be bare.

To get this country of 30 million people back on its feet will be hard and could take some time.

Chavismo drew much of its support from poor areas of Venezuela

Congress might have to, at some point, address the unsustainable policy of giving fuel and gasoline away for free.

That will not be easy because no one likes losing a benefit that they have become used to receiving.

Need for help

Professor Elie Habalian, once Venezuela's ambassador to OPEC, led me through a step-by-step guide of how, in his opinion, the country had squandered its oil wealth and how to re-energise the industry.

"They should accept more foreign investment. It doesn't really matter where it comes from," he told me as we talked at his hillside home overlooking Venezuela's grimy, concrete capital - a monument to the rise and decline of oil in the 1970s and 80s.

"Help is needed for our industry to recover and become competitive - to be able to produce with less costs and more technology," he continued.

All of the above would require a big change of heart and ideology from a radical left-wing government whose president, while wounded, is still in overall charge.

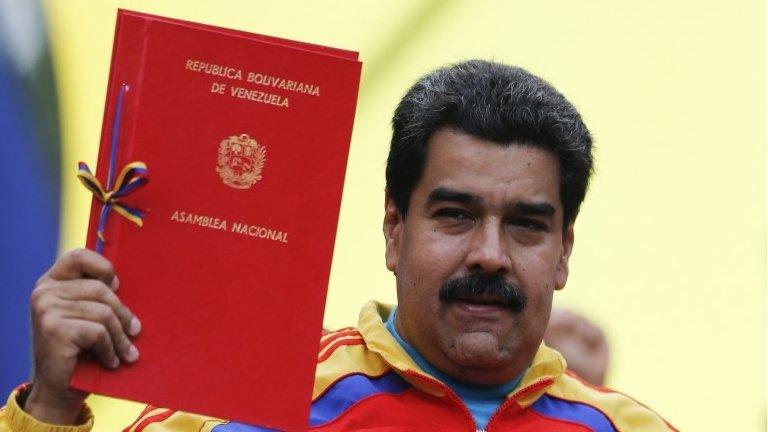

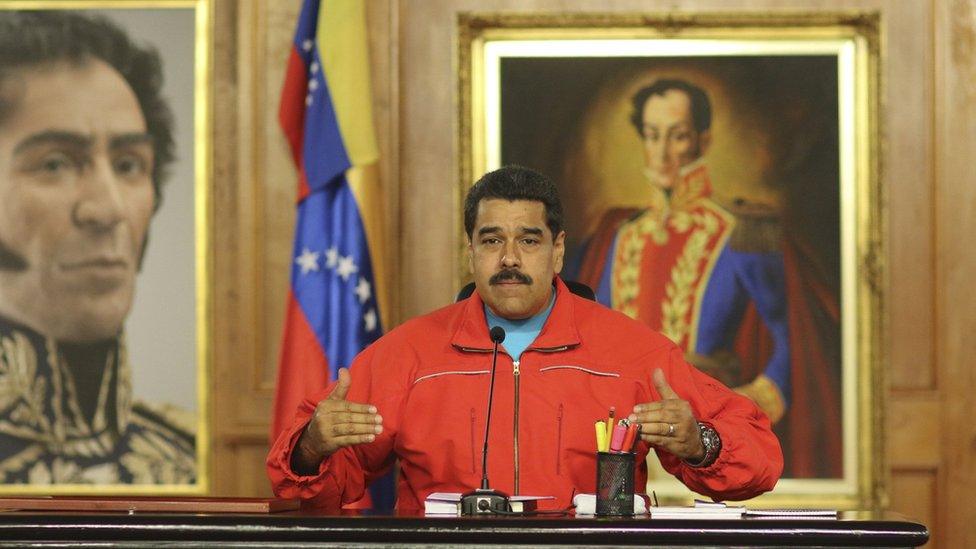

Nicolas Maduro blamed "foreign elements" for his defeat

When he appeared on national television just after the results were declared, President Maduro initially seemed contrite, saying he would accept the voters' verdict.

But then he resorted to type, failing to acknowledge why the opposition had won such a commanding majority in Congress and, again, blamed his defeat on foreign elements seeking to commit "economic warfare" in Venezuela.

As he mentioned Hugo Chavez for he umpteenth time in his downbeat, sober address, it was clear Nicolas Maduro still believes this is a "Chavista" country which has been diverted only temporarily from the path set out by the great revolutionary.

Perhaps, that is not how a majority of Venezuelans feel any longer.

- Published7 December 2015

- Published7 January 2016

- Published7 December 2015

- Published7 December 2015

- Published8 July 2015

- Published3 December 2015

- Published12 November 2015

- Published16 March 2015