People vs politicians: Who can tackle Mexico's corruption?

- Published

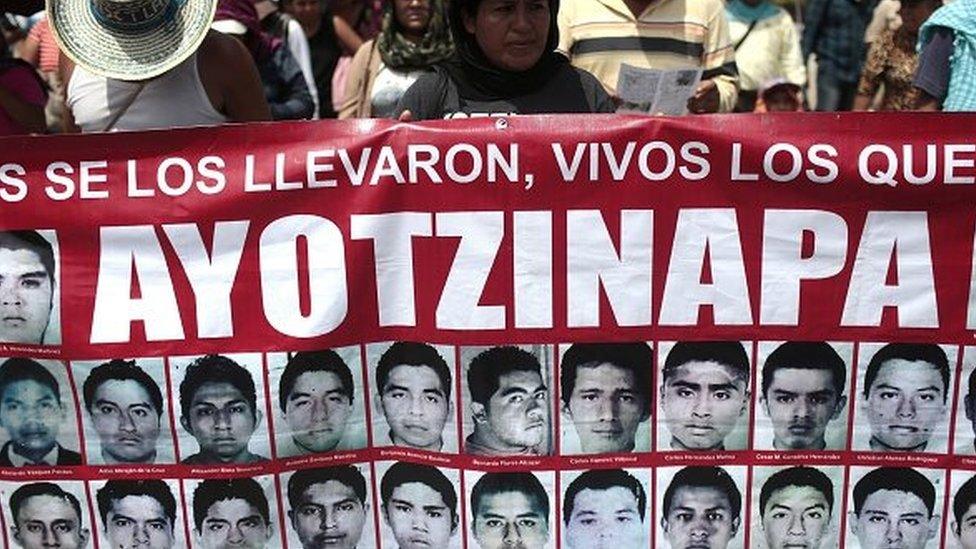

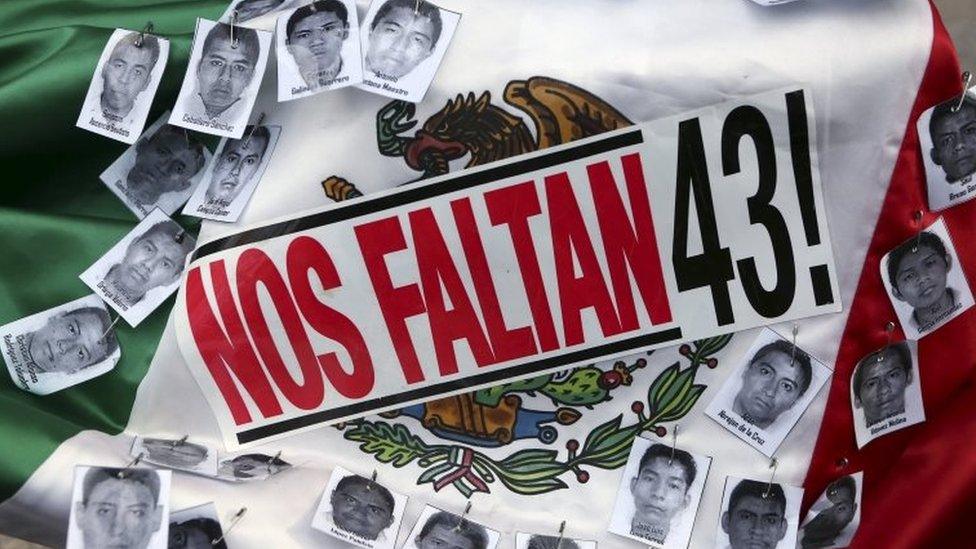

Mexicans have staged a series of protest rallies since the disappearance of the students

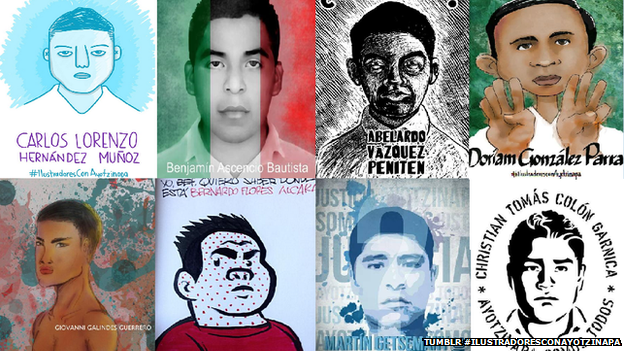

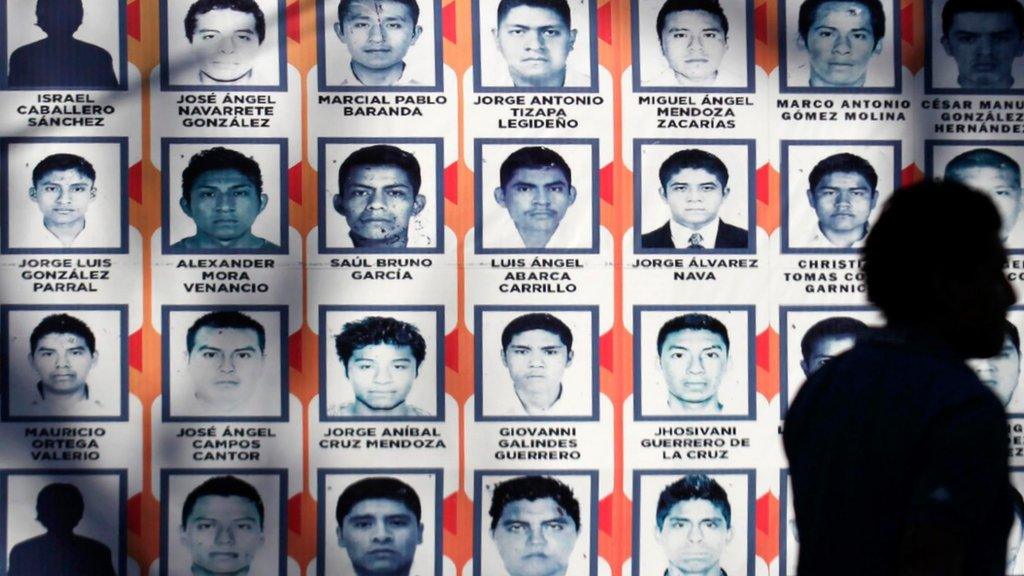

The disappearance of 43 students from Guerrero state in 2014 outraged Mexico, a nation already far too used to high levels of violence.

Now, 18 months on, Mexicans are little wiser as to what happened that night. But one thing that is certain is the involvement of corrupt police in their disappearance.

Fast-forward just a few months from those events in Iguala, and President Enrique Pena Nieto was caught up in a scandal of his own. Dubbed the "White House scandal", questions were raised about how the private house of the president and his wife was acquired.

And just a few weeks ago it was revealed that one member of Mexico's public function ministry, charged with government oversight and accountability, had a dinner of champagne and caviar at London department store Harrods as part of the daily travel allowance last year.

Transparency International's most recent corruption perceptions index, external lists Mexico, at 95th, as the most crooked of all countries in the OECD club of industrialised nations.

Citizen action

Mexicans are fed up with their politicians. Until now, it has been hard to see how they can change the status quo, but a campaign called Ley 3de3 has got people excited.

Ley 3de3 has brought together intellectuals, academics and civil society in what is known as a citizens' initiative.

Ley 3de3 has brought together intellectuals, academics and civil society activists

Under Mexican law, people can introduce a law if the equivalent of 0.13% of those on the electoral register support it. Then Congress is obliged to debate and vote on the issue.

Ley 3de3 has been running a campaign video asking what most unites Mexicans - is it the national anthem, the football team or perhaps tacos? The answer it suggests is instead corruption.

But asking politicians to solve the problem is, it says, a bit like asking a footballer to referee his own side.

Promises broken?

So instead, the campaigners have been signing up people to support them.

The campaign, as well as setting out a new system to deal with corruption, has three important demands - that politicians declare their assets such as houses, as well as their interests such as previous jobs and friendships. And finally they need to prove they pay their taxes.

"I signed because I want a better country - not just for me but for my kids too - where things work better, where not just a few get rich but it's distributed more fairly," says 42-year-old civil servant Roberto Vasquez.

Many Mexicans say President Pena Nieto has reneged on his election promises

Last week, campaigners surpassed their goal and delivered nearly 300,000 signatures to the Senate.

President Pena Nieto's administration has talked a lot about reform. But for many, reality has fallen short of his election promises.

And according to public opinion survey Latinobarometro, external (in Spanish) Mexicans are the least satisfied with democracy among Latin Americans.

"The distinctive thing about this administration is that they claimed that they were going to be very open and different in terms of reforming every single important structural thing," says Eduardo Bohorquez of Transparency International's Mexican chapter.

"So we took their word as a serious one. Reforming the country doesn't only rely on economic reform. And for us reforming the country is changing the incentives of the political structure that created a corrupt regime."

'Cultural matter'

The government has made some efforts. Just months after the "White House scandal", national anti-corruption legislation was introduced.

But secondary laws still need to be passed and there are many who feel the reforms do not address Mexico's problem of impunity - it is estimated that 99% of crimes go unsolved, external (in Spanish).

"I think there has been strong progress in Mexico for transparency legislation, especially at the federal level and newspaper outlets have more capacity to obtain public records and investigate," says Alejandro Aurrecoechea from risk and strategic consulting firm Control Risks.

"We get investigations but often we don't get prosecutions. Anti-corruption institutions must be strong, must have a strong mandate and they must be autonomous to prosecute guilty individuals."

Enrique Cardenas Sanchez says many Mexicans "behave differently" when they travel to the US

But even with new laws, will corruption ever disappear?

US Republican presidential hopeful Donald Trump has weighed in, saying Mexicans are corrupt.

Even President Pena Nieto has said in the past that Mexico's problem with corruption is a "cultural matter".

But this campaign rejects that. The way to a cleaner country is through straightening out its institutions and politicians.

"There are millions of Mexicans who cross over the border in the US and they just behave differently, and the reason I think is because of institutions, because of law enforcement and not having the chance to corrupt anybody," says Enrique Cardenas Sanchez, director of the Centro de Estudios Espinosa Yglesias and one of the campaign's coordinators.

"It's really become a way of living here but I don't think it's something cultural at all."

Impunity

Some call corruption a national crisis, and one that by some estimates costs Mexico 9% of its economic output.

"The big problems that Mexico has to face now - organised crime, violence, poverty, lack of economic growth - all are costs or directly aggravated by corruption," says Juan Pardinas, director general of the Mexican Institute for Competitiveness.

"All of these problems are directly linked to the impossibility of the state punishing members of the police force and politicians that have been corrupted by organised crime.

"If we don't face the problem of corruption, we won't be able to face the other problems."

- Published25 August 2022

- Published30 September 2015

- Published7 November 2014

- Published29 October 2014