Grassroots democracy feels the strain in Venezuela

- Published

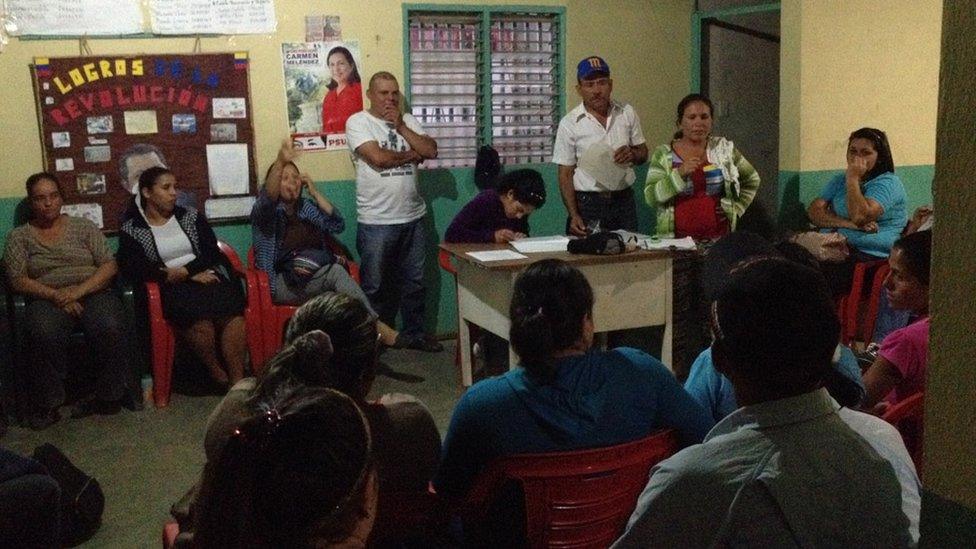

Residents of Monte Carmelo gather to discuss issues affecting their village

Every Tuesday night in the little mountain village of Monte Carmelo, in Lara state in western Venezuela, people crowd into the community hall.

Toddlers sit on their mothers' laps. A gaggle of older children play on the pavement outside while latecomers stand at the doorways listening.

This is a community council, where topics of discussion can range from national coffee prices to complaints about a farmer who lets his cows wander into the road.

There are more than 30,000 community councils in Venezuela, according to government figures.

These neighbourhood committees help to run government social projects and can apply for state funds for improvements to their local area.

Supporters of Venezuela's Bolivarian revolution, the name given by the late President Hugo Chavez to his brand of socialist government, believe that community councils are a new form of grassroots democracy.

But critics say they are part of a parallel state, which is unaccountable and undermines Venezuela's democratic institutions.

'Our voice'

Guadi Garcia comes from a family of rural labourers. She says the community council has given them a voice.

Guadi Garcia says the community council has made a real difference to her village

"It's a way of organising ourselves so we can channel our demands to the government," she says. "It's participatory democracy."

The community council has helped get a new school and better homes for villagers.

Most people in Monte Carmelo back the socialist government of President Nicolas Maduro and his PSUV party but opposition supporters also participate in council meetings, she says.

In the neighbouring village of Palo Verde, the split between government and opposition supporters is more evenly balanced.

But unusually for a country as politically polarised as Venezuela, both sides work together.

The community council helps to run a local clinic, which is part of a government scheme that puts doctors in poor areas.

It is held on the porch of Maria Torres' home.

Doctors tend to patients on the porch of Maria Torres' home

Ms Torres supports the opposition and is a spokeswoman for the council.

"We don't care what party anyone belongs to, we are all working together for the community," she says.

But council members here are unhappy because their responsibility for distributing desperately needed state-subsidised food to villagers has recently been taken over by the PSUV's electoral campaigning wing, the Unidades de Batalla Bolivar-Chavez (UBCh).

They allege that this organisation has been withholding food from people who voted for the opposition in parliamentary elections held in December.

Milagro Colmenares is a PSUV member but says she was angered by what she saw other PSUV members doing.

Milagro Colmenares says the new way food vouchers are distributed does not work

She says that even though the UBCh brought about 300 food vouchers, the council was given fewer than 30 to feed 120 families.

"We made a complaint about this because food is something sacred, food should be for everyone," she says, but they have not yet received a response.

Locals say that since their complaint food distribution has become fairer.

Parallel power

The case illustrates the arbitrary and makeshift nature of Venezuela's new local power structures.

Margarita Lopez Maya is a professor at the Central University of Caracas.

Margarita Lopez Maya says the community councils have become a parallel state

She says that when the community councils were first set up they had to report to the elected local municipalities.

But after 2006, when President Chavez's socialist revolution entered a more radical phase, they started reporting directly to the presidency.

Prof Lopez Maya says that with the responsible power far away in Caracas, accountability was lost.

"The government began building a state that was parallel to the state outlined in the constitution," she says.

Under new laws passed by the socialist government, the councils were given more and more powers, by-passing the traditional municipal and regional authorities, she says.

Some people have been pressured by their neighbours to join the PSUV and then become council members so that their council stands a better chance of getting funds, she alleges.

'Political tool'

Freddy Guevara, an opposition lawmaker in Venezuela's National Assembly, is also convinced that the government favours councils which back it politically.

"It's a good idea that's been perverted and used only to subjugate the people to the will of the ruling party," he says.

He says that because the definition of what constitutes a community council is not clear, the government can pick and choose which ones it recognises and which ones it does not.

"You can be elected by your neighbours and follow all the steps outlined in the law, but the government has the last say," he explains. "If it doesn't recognise you, you can't have funds, you can't do anything."

- Published17 March 2016

- Published6 March 2016

- Published25 February 2016