Marijuana law reform: Mexico's president changes tack

- Published

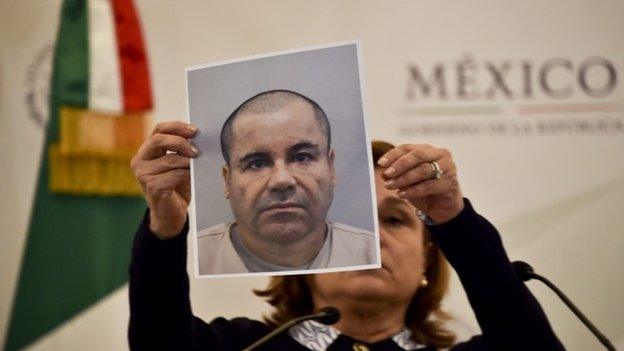

Drug smuggling on the US-Mexico border remains a huge problem

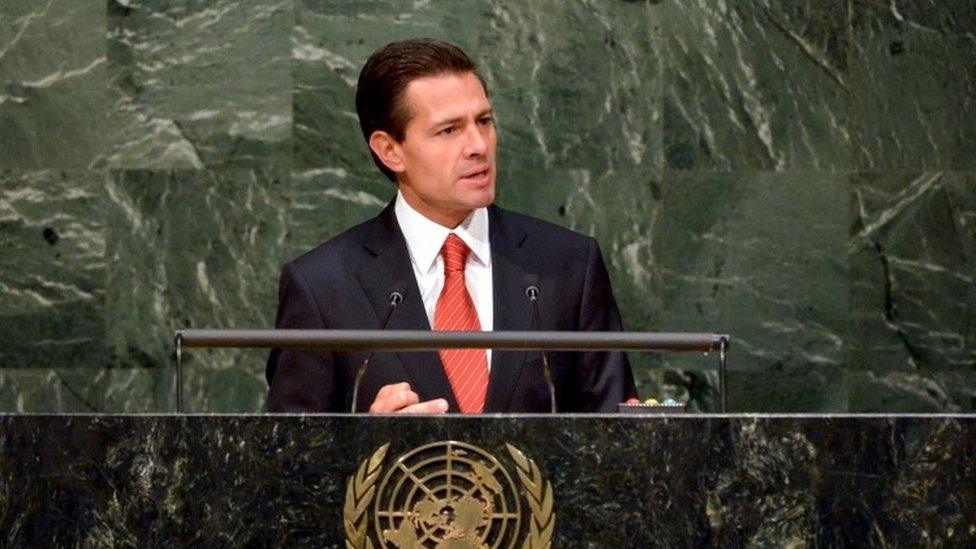

It has been quite a change of heart for Mexico's President Enrique Pena Nieto.

Only a few months ago, he said he was not in favour of legalising marijuana. Now he is making steps to allow the use of medical marijuana and considering changes to decriminalise small quantities of the drug for recreational use.

The news came just two days after he addressed the United Nations General Assembly at a special session on drug policy - a meeting that was called for by Colombia, Guatemala and Mexico in 2012 and seen as a chance to re-think the current strategy of fighting drug-trafficking.

In fact, President Pena Nieto was not even going to attend the meeting in New York until late last week when he made a U-turn.

Perhaps he realised that not showing up would send a pretty stark message about the importance he places on improving the lives of millions of Mexicans.

Turf war

"My country is one of the nations that has paid a high price - an excessive price - in terms of peace, suffering and human lives, lives of children, young people, women and adults," the president said at the UN. "We know the limitations and the painful implications of the prohibitionist enigma."

Drugs are more widely available in Mexico than ever before, commentators say

President Pena Nieto says that his country has paid an excessive price for combating the drugs menace

The crackdown on drug cartels has led to thousands of disappearances and deaths

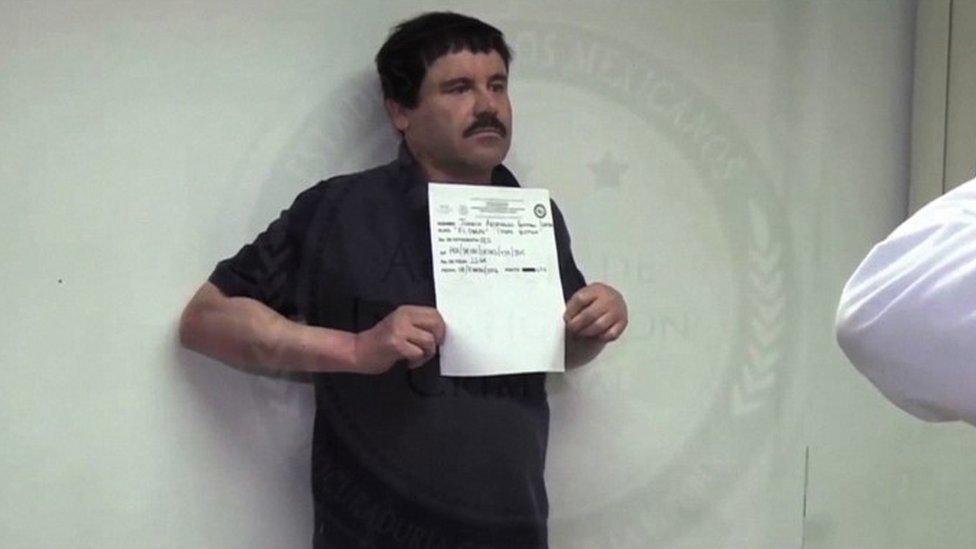

The so-called war on drugs that was introduced in 2006 by his predecessor Felipe Calderon was aimed at cracking down on cartels with military might.

But rather than making things better, it has resulted in more than 100,000 deaths, 27,000 disappeared and a turf war among criminal gangs.

In the wake of the disappearance of 43 students in the town of Iguala in September 2014, there is a lot of anger about human rights abuses and the level of violence in the country.

Back in November, four people won a Supreme Court case that ruled that prohibiting people from growing marijuana for consumption was unconstitutional. It was seen as a historic vote that would pave the way to liberalising drug laws in the country.

Businessman Armando Santacruz was one of the plaintiffs. For years he has worked to improve security and justice in the country through the organisation Mexico United Against Crime. But after a while, he realised they were missing a piece of the puzzle.

"The elephant in the room that nobody was talking about was drug policy. In other words anything we did, if we did not address drug policy, would be fruitless," he says.

Supporters of reforms to the drug laws argue that it they would bring an end to turf wars among criminal gangs.

"Drug policy was the main driver behind violence, behind the huge power that the cartels were achieving, that organised crime was achieving through the inordinate profits they were getting from drugs."

It was then that he and three other activists formed the small club called the Mexican Society for Responsible and Tolerant Use (SMART, in Spanish). They began their campaign in 2013 and won the Supreme Court case five months ago which paved the way for a national debate on marijuana.

"I think it's hugely significant," says Hannah Herzer of the Drug Policy Alliance regarding the conversations and changes going on in Mexico.

"It wasn't done because those that are behind it want to see marijuana consumption go up. It's done because this is the smarter way to address a problem that is not going away."

For Mr Santacruz, full legalisation of marijuana - and eventually regulation of other drugs - makes economic and political sense.

"It's a very good way of depriving organised crime of one of its easiest sources of profits and cash-flow," he says.

"The more you deprive organised crime of massive cash flow the more you change the power equation between government and organised crime and make it easier for them to fight them."

Racketeering and extortion

But not everyone agrees.

"It's a fallacy, a huge lie and a big deception," says Consuela Mendoza Garcia, the president of the National Union of Parents and Families.

"I think that drug traffickers must be laughing about these kind of measures because marijuana isn't a business - there are lots more drugs but not only that - there's racketeering, kidnappings, extortion. That won't change because they legalise marijuana."

While the political debate continues, others are focusing on changing the future through education.

Claudia Rodon Fonte works with the Collective for an Integral Drugs Policy. She thinks the need for more open debate is more necessary than ever.

Claudia Rodon Fonte wants fewer lies told about drugs so young people can make informed decisions

"Drug consumption here is lower than 3% of the population," she says. "That's rising because many of the drugs that used to go to the US are now staying in the country. Much of the time, as payment for transit. So now there's much more supply than there was before."

She thinks too many lies are told about drugs which does not help young people make informed decisions.

One of the projects she works with is setting up small laboratories at festivals where users can get their substances tested and make sure they are safe.

But it is a grey area - what she is doing is not illegal but some controlled substances to test the drugs properly are hard to come by. With a more liberal drugs policy, their work could be made easier.

What is happening in Mexico is an important step but it does not go far enough for people like Armando Santacruz. He is convinced a drastic change in approach is the only way to make things better.

"Mexico has had more people disappear than Argentina and Chile together during their whole military regimes," he says. "We've had more Mexicans die in the drugs war than the US has had in Afghanistan and Iraq together. It's unreal. There's no way you can justify that kind of human cost."

- Published22 April 2016

- Published27 March 2016

- Published20 April 2016

- Published20 April 2016

- Published14 February 2016

- Published2 March 2016

- Published29 December 2015

- Published20 July 2015

- Published5 November 2015

- Published4 October 2024