Colombia Farc guerrillas prepare finally for peace

- Published

The BBC's Will Grant gained access to a Farc camp in Western Colombia

As the speedboat navigates its way along the winding course of the Naya River in western Colombia, the signs soon start to appear that you have entered Farc territory.

Banners have been posted every few kilometres, emblazoned with the faces of the leadership of Marxist guerrilla group the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia - both past and present.

They say: "52 years seeking peace," citing the length of Colombia's arduous civil war, one of the longest armed conflicts in the world.

One of the bloodiest too: as many as 220,000 lives are thought to have been lost during those years of fighting, which only now look like drawing to a close as a peace deal with the government moves ever closer.

We spend a couple of hot and muggy days in one of the riverside villages poking out among the banana and tropical cedar trees, killing time by drinking weak coffee and playing cards until our contact appears.

Part of the rebel army's civilian support network, he ushers us back on to a boat and takes us deeper into the jungle.

A day later, a group of guerrillas are waiting for us at the bottom of a rocky brook, M-16's slung over their shoulders.

The rebels go through drills several times a day

They guide us in a trek up along steep mountain paths and across streams until the camp of the 30th Front of the Farc's Occidental Bloc emerges beneath the thick canopy.

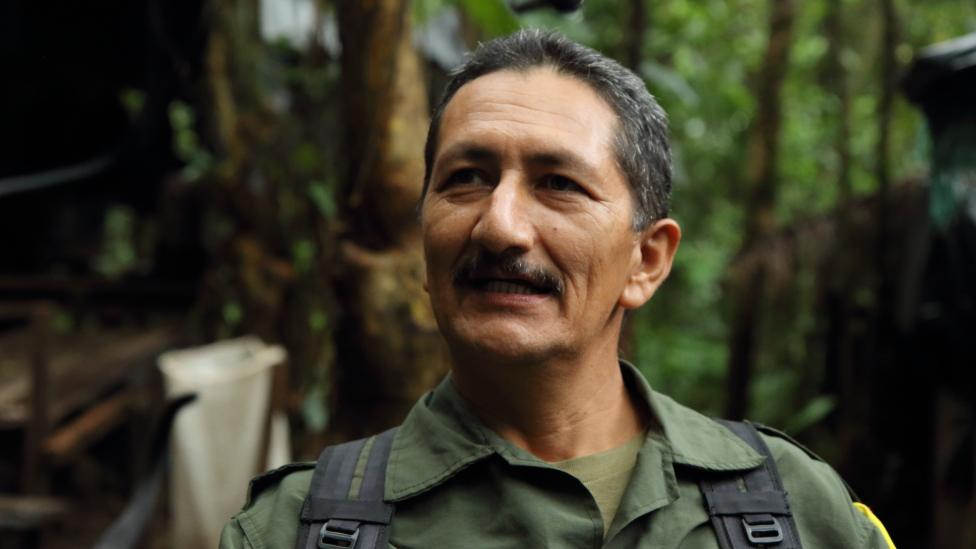

Roque is the commander of the camp

The camp commander, a wiry moustached man called Roque, welcomes us with the hospitality Colombians are famous for.

While the Farc's shameful history of kidnapping - including journalists - shouldn't be overlooked, it is also immediately clear that we are in no danger and that this isn't the ill-advised trip that it might have been a number of years ago.

The Naya River marks the dividing line between two of Colombia's Pacific departments, Cauca and Valle de Cauca, and Roque explains the area has been calm for months.

As someone who has spent the past 33 years at war, the quiet still makes him twitchy.

Despite the historic agreement being reached in Havana, the local commander feels like the group is "effectively already in a bilateral ceasefire [with the military]", he says over a meal of white rice and a meat-less sancocho, a Colombian stew.

"There's such a great sensation of tranquillity that it almost makes you nervous," he says.

Keeping weapons clean is a priority

Farc:

Formed in 1964 as a peasant rebel army in response to aggression by the state, Farc has demanded agrarian reform and land redistribution ever since

In the early 1990s, it began to finance itself through the illegal drug trade.

About 220,000 people have been killed in the 52-year civil war

During the presidency of Alvaro Uribe, the organisation was militarily pummelled as scores of combatants died in battles and skirmishes across Colombia. Others deserted under the intense pressure of the military.

Peace talks with the government of President Juan Manuel Santos, begun in Havana three years ago, have now entered the final stretch

The Farc in the 21st Century is a strange beast.

Gone is the bipolar vision of the Cold War, and gone too are most of its original intellectual architects, many killed in combat.

Today, somewhat anchorless, the rebels continue to go through motions of an armed insurgency - but they know a new future is beckoning.

Camilo has lived in the jungle for his whole adult life

They remain primed for war; machine guns by their beds, handguns under their pillows, all night lookouts keeping watch for an enemy that no longer seems to be searching for them.

Every day begins before dawn, with the first troop inspection at 05:00.

After coffee and breakfast in the dark, daylight begins to break and the morning's activities begin.

Whereas once they might have carried out stealth missions to set bombs around military checkpoints or ambush an army patrol as it makes its way through the forest, now they hold "capacitation workshops" to discuss the latest developments in the peace process.

The guerrilla army - of which this camp contains only a handful of combatants - is still largely made up of young men and women from poor rural backgrounds.

At 27 years old, all Camilo has known his entire adult life is the jungle and the Farc.

He admits that it shows up in some unlikely ways: he has never had a hot shower, for example, as he and his comrades bathe in the icy waters of a spring.

Softly spoken and with a disarming smile, Camilo hopes to put his guerrilla skills to good use once the peace is declared.

But what would a Farc explosives expert do outside the jungles of Colombia? "Maybe a civil engineer," he suggests.

"In terms of carrying our arms, we're still ready for war. But psychologically, we're already at peace," Camilo adds with an erudite turn of phrase that will serve him well in a future Farc political party.

Tania signed up while still a teenager

Like Camilo, Tania joined the organisation while still a teenager.

She chose her nom de guerre after Tamara Bunke, Tania the Guerrilla, the East German revolutionary killed fighting alongside Che Guevara in Bolivia.

She used to admire the Farc women who came through her village dressed in green fatigues "carrying their backpacks through the rain, all of them so good-looking".

They spoke to her about joining up when she was still a girl, and she doesn't regret her decision to enlist but admits they left out the hardest detail: she would have to kill other Colombians.

"It's definitely not easy," she says. "After all, we're all brothers, all children of the same country. But that is just the way of the world."

Tania talks to us on the sidelines of an inter-camp football match, held in a jungle clearing the Farc has turned into a makeshift pitch.

The women's matches are as fiercely contested as the men's, and Tania says she loathes the traditional gender roles of wider Colombian society.

But the Farc bans women from having children in their ranks, and about 150 cases of allegedly forced abortions within the group are currently under investigation by the attorney general's office.

"As a woman, I hope to have my own family one day, but not while we live in these conditions," Tania says, referring to both life in the jungle and her uncertain future in a post-conflict Colombia.

Most guerrillas say their main fear is retribution from the country's paramilitary groups and argue that the state must guarantee their security.

After a deal is reached, many combatants will live in "concentration zones" or "encampments", the exact details of which still aren't clear.

Football is a popular recreation

But given that the Farc is largely financed through drug trafficking, some doubt whether the rank and file will be able to quietly step away from the lucrative cocaine trade without another glance over their shoulders.

Daily life in the camp

Comandante Walter Mendoza, of the Occidental Bloc, insists his troops will comply with the order to disarm when he gives it.

"They know what they must do," he says. "We receive our orders from our superiors at the talks in Havana. We know we're about to take a very important step."

Still, he clarifies that they will not hand their guns in to the state in a televised event.

"That media show they want - of us suppliantly giving over our weapons - that show will not happen," he says.

As we leave the camp, we again speed past the Farc's propaganda on the riverbanks.

Over and over the words flash by: "52 years seeking peace."

Many Colombians reject such a one-sided description of the violent civil war.

But, if its slogan is to be believed, the Farc is now tantalisingly close to finding it.

- Published16 May 2016

- Published24 March 2016

- Published10 February 2016

- Published4 February 2016

- Published19 January 2016

- Published17 December 2015