100 Women 2016: Bringing up my son as a feminist

- Published

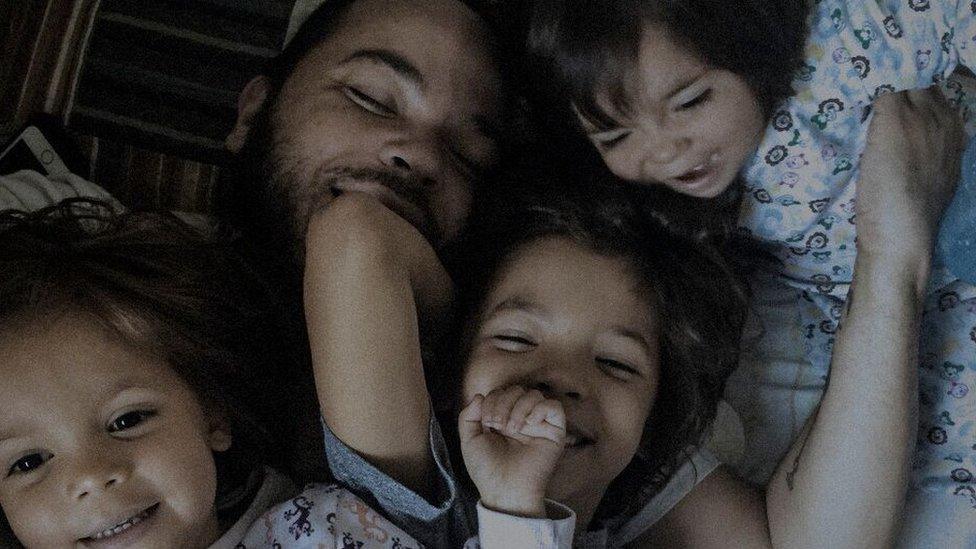

Photographer Pedrinho Fonseca is determined to bring up his young son Joao as a feminist, in contrast to the intense chauvinism he himself witnessed as a child in his home region in Brazil. He tells BBC's 100 Women about what influences made him change course, and how he tries to help Joao move away from perceptions fostered by an entrenched culture.

I come from a very sexist place.

I was born in the north-east of Brazil - a poor region that absorbed what was worst during the time of Portuguese colonial rule: the concept of domination. We were populated by white and wealthy men who enslaved Africans and left us a legacy that relationships should be ruled by this logic.

Men from this area have grown up with the notion that they are owners; they have possessions, which can be land or other human beings, especially women. Thus they are responsible for bringing home the money, but no affection.

And women are expected to serve them. Centuries later, we are still growing up getting this same information that we can do anything - and that women exist to please us only. This twisted scenery has built generations of complete sexism.

No gender issue

But many years later, with the arrival of my son, João, I realised that I needed to be a point of reference for him, completely different from the men I had known as a child, so he could grow up with another perception of the world.

Watching a child grow up:

Have you seen the beginning of a river? It is tiny. There is no water flow, nothing to show that this small puddle will eventually be defined by a course, miles away, as an abundant river. Every river is, in its essence, a surprise for those who follow it.

Suddenly it has crossed rocks, poured through valleys, sculpted green banks, jumped through waterfalls, wet the feet of women washing their family's clothes.

This is what it is like to watch a child grow up.

The men, the providers, fold their arms, ignoring the most simple human tasks such as cleaning the house, making the bed, cooking, washing the dishes, watering the plants, shopping for groceries. Their duty is to walk away in the morning, work to bring back some money, come back to sleep, and the next day, start all over again. This pattern is the norm for many generations, even the current one, particularly in north-eastern Brazil.

I was raised in this atmosphere. And this was the template I was used to. It never occurred to me to question it because it is such an entrenched part of the culture, a symbol of historic domination ruled by the idea that women exist to serve.

My course, my natural perception of this world where men have a voice, and women do not, was interrupted by the birth of my first child. Suddenly here was someone who might follow the pre-established course for a Brazilian man - but I couldn't allow him to do that.

Now, there was another man in my house, and his arrival brought the possibility of change, for both him and me.

What is 100 women?

BBC 100 Women names 100 influential and inspirational women around the world every year. We create documentaries, features and interviews about their lives, giving more space for stories that put women at the centre.

We want YOU to get involved with your comments, views and ideas. You can find us on: Facebook, external, Instagram, external, Pinterest, Snapchat, and YouTube.

Spread the word by sharing your favourite posts and your own stories using #100women

Other stories you might like:

'I married a man to keep my girlfriend'

'Adults are so obsessed with children they have no time for important things'

Tips for fathers of boys

Invite him to wash the dishes with you. Then, you can clean the house (including the bathroom!). And, later I think you'll like cooking together. It is fun and probably will make your son understand there should be no gender issue when you're taking care of your own home.

Play football with him and his friends - don't forget to invite the girls to play with you!

If you're the father, never, never, never interrupt your son's mum when she's talking - it's important for him to follow your example.

And, please: tell your son, day after day, there is no reason to think women like violence. They don't. In fact no-one does.

I, who had never previously appreciated the role of my mother in my life, started to see her in another way. She had virtually raised me by herself, played all the parts: she worked all day long, but also took care of me all the time, cooked, gave me love, and soothed my small childhood and adolescence pains.

I, who had never understood that a partnership could have a political and ethical dimension and that I could fight for gender equality, discovered even more about women's power through my wife, Lua. And listening to her voice inside the house and outside in the world, defending women's potential, João can start to follow a course I didn't.

Joao must get clear values early on, before he becomes a man, his father believes

Fonseca believes it is only possible to achieve gender equality if we start with our children

Pedrinho's wife Lua has been one of the key influences on his thinking

I understood that it is impossible to achieve social sexual equality unless we start with how we treat our children. And when I show him my affection and love, when we share household chores between the whole family (Joao has two younger sisters), when he realises that the norm should be to respect women's voices and bodies, I feel that he can observe the world from a new place. Not somewhere that I, nor a huge portion of my generation, came from, but definitely where we must go.

'Done something wrong'

Does Joao ever say anything sexist? Yes - it happens when he is distracted. He is a young child who is still hit by sexist values. For example, he told us that during a school break all the pupils ran to the playground to play football. When they got there, the boys told the girls they should find something else to do.

He brought up this story during dinner - because, according to him, he "felt he had done something wrong, but did not know what". We talked and told him that the mistake was to try and decide for the girls what THEY should do and to assume that playing football could not be a 'girl thing'.

We talked, he listened, asked questions and the next day when he got home from school, told us he had apologised to the girls for what had happened.

All photographs: Pedrinho Fonseca