Venezuelans cross into Colombia as crisis deepens

- Published

Thousands of Venezuelans are searching for a new life in Colombia

At 05:00 in the morning, a steady stream of Venezuelans heads into Colombia.

Many have queued overnight, waiting patiently for the Simón Bolívar International bridge to open. Some 25,000 people cross the bridge into Colombia every day.

It is a short walk between the two countries but with the political and economic crisis in Venezuela deepening, the two neighbours now seem worlds apart.

Venezuela is suffering from acute shortages of medicines, hospitals struggle to treat patients and staple goods have become scarce and unaffordable to many.

Watch:

Mothers cradle their babies, bringing them to the hospital in the town of Cúcuta, on the Colombian side of the border, to get them vaccinated.

Families push poorly relatives in wheelchairs. Others cross into Colombia with empty suitcases, filling them up with food and supplies they cannot get in Venezuela.

Two women with a baby in a pushchair walk past the border guard, muttering: "What a humiliation." They are clearly embarrassed they have to do this.

Crossing the border for food

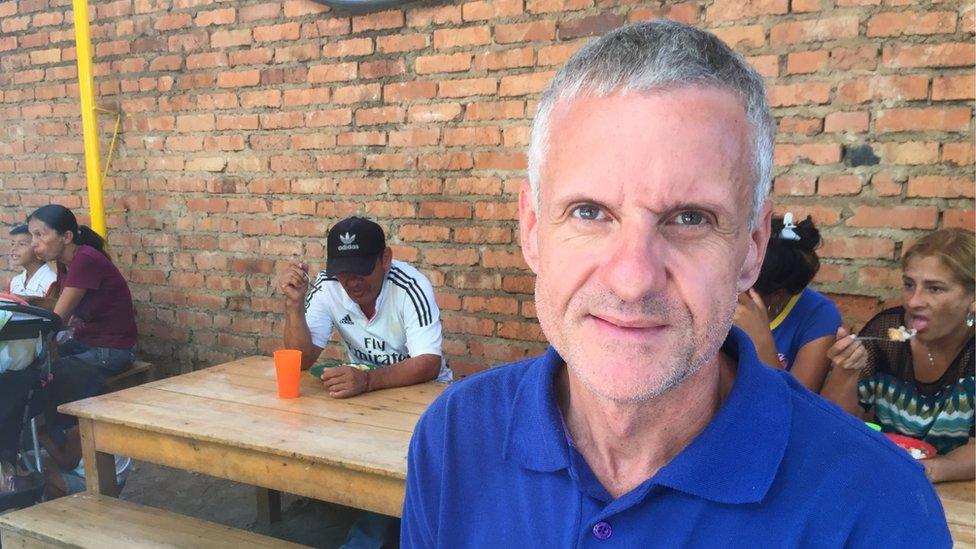

The local church in Cúcuta is feeding between 600 and 2,000 people a day in an open-air courtyard filled with plastic tables and chairs.

The church in Cúcuta offers food to those in need

Hundreds of people come to eat here every day

Verónica Mendoza, 24, is five months pregnant. She is tucking in to a meal of rice, beans, potatoes and mince with her mother, Mariluz.

The two women travel two hours every day from Venezuela to sell fruit at a market in Colombia.

They cannot find work back home. They come here for their only proper meal of the day.

"Look at the weight I've lost," says Mariluz, grabbing her once fleshy arms and showing the loose skin. "I used to be healthy and strong. But we have to walk such a long way and work so hard."

Verónica Mendoza and her mother Mariluz rely on the food they are given at the church in Cúcuta

Mariluz's case is not rare. Recent research [in Spanish] suggests, external that three-quarters of Venezuelans lost weight in the past year, an average of 9kg (20lb).

Living on the streets

The Colombian government recently introduced "border mobility cards" to allow Venezuelans to go back and forth across the border without the need for a passport.

More than 700,000 people have applied for the scheme so far.

But some like Carlos Alberto Ledesma, a professional jazz musician from Caracas, want to stay in Colombia for good.

Carlos Alberto Ledesma says he cannot make a living as a musician in Venezuela any more

Mr Ledesma arrived in Cúcuta eight days ago. "I spent a year living on the streets," he says.

"I stopped working in Venezuela because the bars aren't open, half of the musicians have gone."

Official figures put the number of Venezuelans who have left their homeland for Colombia because of the crisis at 300,000. But the actual number is thought to be much higher.

The influx is putting strain on communities in Colombia, which have lived through more than five decades of armed conflict between left-wing guerrilla groups, the armed forces and right-wing paramilitaries.

Luis Fernando Niño López is the secretary for victims, peace and post-conflict for the province of Norte de Santander, where Cúcuta is located.

"At the moment, there's a pretty big flow but not everybody stays," he says of the Venezuelans arriving in the region.

"But what's going to happen when they can't go back because [Venezuelan President Nicolás] Maduro closes the border or because armed groups that control the border won't let people go back?"

Sheltering Venezuelans

At a shelter run by the Scalabrini International Migration Network in the centre of Cúcuta, the growing scale of the problem is evident.

Between January and June, 650 people came through its doors. In August alone, there were 850 people.

Mr Franklin Díaz, who runs the shelter, says those who come to the shelter are in urgent need of attention and more should be done to help them.

"The action of the authorities is fundamental, they are the ones who manage the resources."

Many of those crossing into Colombia from Venezuela originally fled the armed conflict in Colombia.

Nereidis Ascanio is one of them. Her father was killed by paramilitaries so her family left for Venezuela when she was a child.

Nereidis Ascanio's family fled Colombia when she was a child but now she is back and looking for work

A single mother, her two little boys have Venezuelan nationality.

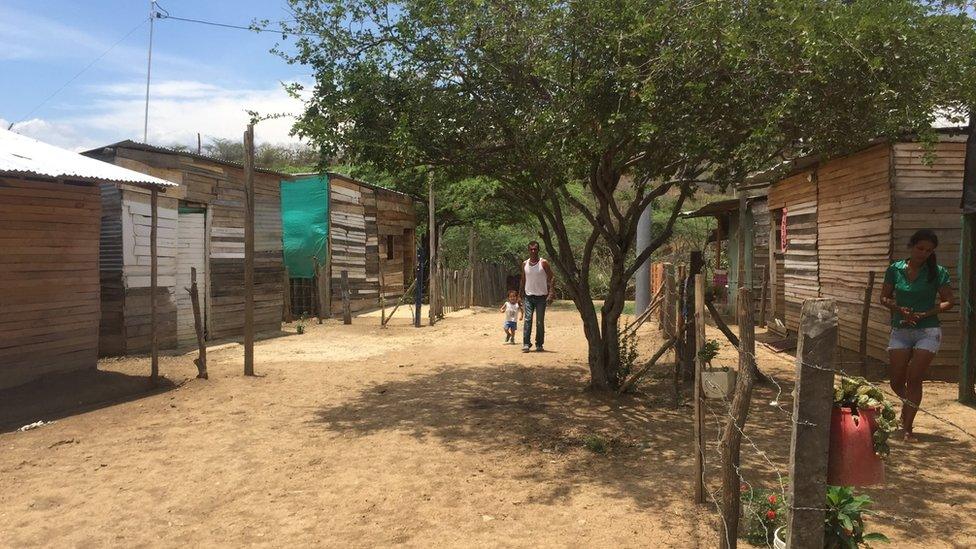

She recently returned to Colombia and now lives in a little shack made out of wooden beams and a corrugated iron roof on the outskirts of Cúcuta. The tarpaulin walls do not even cover the entire shack.

Some Venezuelans have erected makeshift shacks on the outskirts of Cúcuta

Ms Ascanio is desperate. "I need to find food for my kids," she says while she wipes away tears.

"And I need to find a job that will allow me to look after my boys."

Getting stuck in Cúcuta

Other Colombians left for Venezuela when the oil industry started booming there in the 1980s.

With oil prices now low and the economic crisis in Venezuela worsening, they too are returning in large numbers.

Many arrive in Colombia with great expectations of a new life.

But Venezuela's triple-digit inflation means their savings in Venezuelan bolivares are worthless once converted into Colombian pesos, so many get stuck.

In the middle of the town is a roundabout with a large sculpture which reads "I love Cúcuta". Some people are curled up sleeping in the letters "c".

Jeferson José Gutierres is one of those sleeping rough along with his wife and their three children.

Jeferson José Gutierres remains upbeat, he says life in Cúcuta is better than in Venezuela

He came here a month ago and cannot find work.

But he says life in Cúcuta is still better than in Venezuela and he is not planning on going back while President Maduro is in power.

"I'll return when Maduro goes," he says.

"He's a president who spends money while his people die of hunger."

- Published29 July 2017

- Published19 July 2017

- Published22 May 2017