Mexico election: Five things you need to know

- Published

Andrés Manuel López Obrador's supporters are trying to make their candidate appear cuddly

Mexican presidential elections come around every six years, and since 1929, they have been won by men from either of the two main parties, the PAN or the PRI. So why should you care what happens on Sunday?

1. They are the biggest election in Mexican history

Not only are 88 million Mexicans entitled to vote, there are a record number of races too.

The most watched will be that for the top job, the presidency.

Key facts:

There are four candidates running and each has their own piñata

To be held on 1 July

Winner will replace President Enrique Peña Nieto from the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI)

In Mexico, presidents are restricted to a single six-year term, so Mr Peña Nieto cannot run again

Polls suggest left-wing candidate Andrés Manuel López Obrador has a big lead over the rest of the field

Three more candidates are in the running: conservative candidate Ricardo Anaya, governing party candidate José Antonio Meade, and independent Jaime Rodríguez

In total, there are a whopping 18,000 elected posts up for grabs, according to Mexico's National Electoral Institute.

All seats in Congress, both in the lower house and in the Senate, are up for election. In 30 of Mexico's states, there will be elections for state congress and for mayors as well.

See more stories and videos like this

Moreover, residents in eight states and in Mexico City will cast their votes for governors.

So whoever wins and which parties make gains, there will be changes at the federal, regional and local level.

2. Mexico may be in for some change at the top

Since 1929, when the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) was founded, it has dominated Mexican politics. For 71 years straight, from 1929 to 2000, its presidents governed the country uninterrupted.

José Antonio Meade is running for the governing party PRI and has its well-oiled party machine behind him

In 2000, its traditional rival, the conservative National Action Party (PAN), came to power. For the next 12 years - first under President Vicente Fox and then under Felipe Calderón - the PAN was at the helm.

It was during these years that the Mexican government declared a "war on drugs", and the casualties in the battle against Mexico's drug powerful cartels shot up.

Neither the PAN nor the PRI, which won the 2012 election with its candidate Enrique Peña Nieto, have been able to get the violence under control.

What is different about 2018 is that a candidate who is neither from the PRI nor the PAN looks set to win. He is Andrés Manuel López Obrador, a 64-year-old left-wing politician who says he will "revolutionise" Mexican politics.

A win for him would be a political earthquake in a country where almost all voters alive today have never been governed by a president who was not either from the PRI or PAN.

3. Mexico matters

Mexico stunned football fans worldwide when its team showed up Germany's weaknesses in their opening game at the World Cup. Its fans' joyous celebrations have become legend.

But Mexico is much more than the sombreros and masks its passionate fans like to don.

The football distracted some from the election campaign

It is the second largest economy in Latin America and a major oil exporter. But Mexico's economy has suffered from widespread corruption, and the high levels of violence wracking the country have led to some firms pulling out of the most affected areas.

Growth has slowed and many Mexicans are angry that President Peña Nieto has not done more to kickstart the economy.

Mexico has also been in the international news for two other reasons: the North American Free Trade Agreement (Nafta) and migration. Both matter to its powerful northern neighbour, the US.

4. It's the country Trump loves to bash, and Mexico is hitting back

While US President Donald Trump has managed to alienate quite a few nationalities, Mexicans have come in for more abuse than most.

During his campaign, he said that Mexicans coming to the US were "bringing drugs". He added: "They're bringing crime. They're rapists. And some, I assume, are good people."

Mexicans have mocked the idea that their government will pay for the US-Mexico border wall

In order to keep the "bad hombres" out, he has proposed building a wall on the US-Mexican border, which he wants Mexico to pay for.

More recently, he has criticised Mexico for allegedly not doing enough to stop Central American migrants from crossing Mexico en route to the US.

Who the next Mexican president will be and how he deals with President Trump and his plans to renegotiate Nafta and build a border wall will therefore be key to US-Mexican relations.

The candidate who has been most critical of Mr Trump during his campaign is left-winger Andrés Manuel López Obrador, also known as "Amlo".

He has said he will make Mr Trump "see reason" and his staunch opposition to the US president has won him extra voters, analysts say.

But on the matter of children being separated from their migrant parents at the US border, conservative candidate Ricardo Anaya went even further than Mr López Obrador, saying that "it reminds me of what the Nazis did in WWII, it's completely unacceptable".

There have been protests in Mexico against President Trump's policies

The governing party's José Antonio Meade has also confronted President Trump. He condemned the tariffs the US recently imposed on Mexican steel.

In a tweet, he warned: "Don't play with Mexico. We will defend our jobs, our markets and our workers."

5. It's been a deadly year

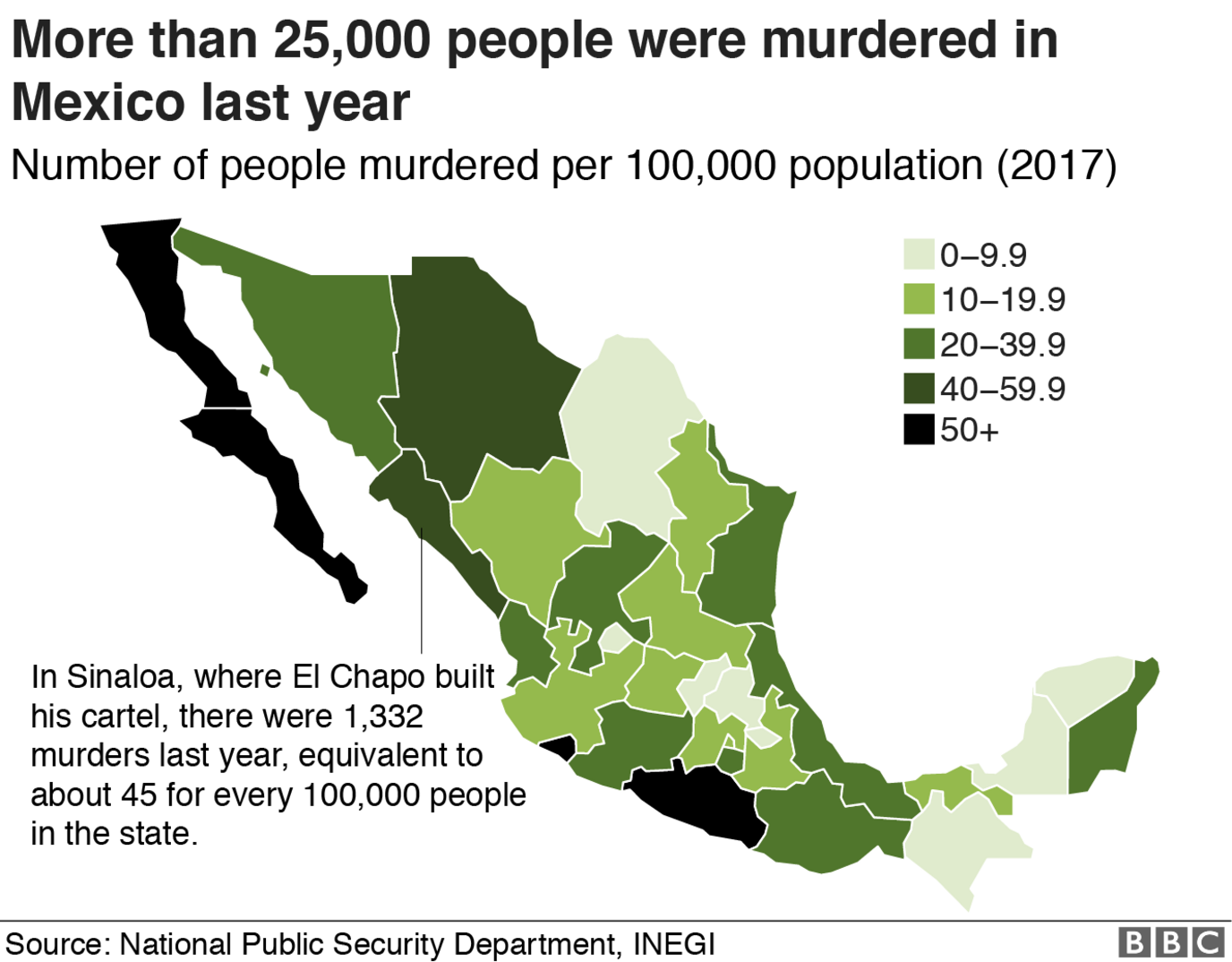

The elections have been held against a backdrop of record levels of violence, with official figures suggesting that more than 25,000 people were killed in Mexico in 2017.

Running for local office in Mexico can be a "death sentence" says candidate for local mayor Jacko Badillo

Politicians have been far from immune. Between September, when registrations for candidates opened, and the close of campaigning on 28 June, 133 politicians were killed, according to figures gathered by a consulting firm.

Most of those killed were running for local government posts and were campaigning in areas where drug cartels often wield more power and influence than local law enforcement, or where local law enforcement colludes with the gangs.

One thing many voters said they would like to see was an end to the violence. How to bring that about will be the biggest challenge for the candidate who will be sworn in as Mexico's next leader on 1 December 2018.

- Published11 July 2019

- Published2 July 2019

- Published20 October 2016