Migrant children in the US: The bigger picture explained

- Published

Reports of appalling conditions for child migrants led to protests in Texas

"Severely neglected" children detained in what have been called squalid conditions, as well as deaths on the US-Mexico border, have brought the treatment of migrants into focus in the US.

Lawyers who visited a border patrol facility in Clint, Texas, have described overcrowded cells, with children locked up without adult supervision or sufficient access to food or showers.

The border authority has said it is trying to provide the "best care possible", but that it "urgently" needs additional funding to help the children, some of whom entered the US independently, and some of whom have been separated from their families.

But why this is happening, and why now? Here, we have looked at three key pieces of context that will help you understand the fuller picture.

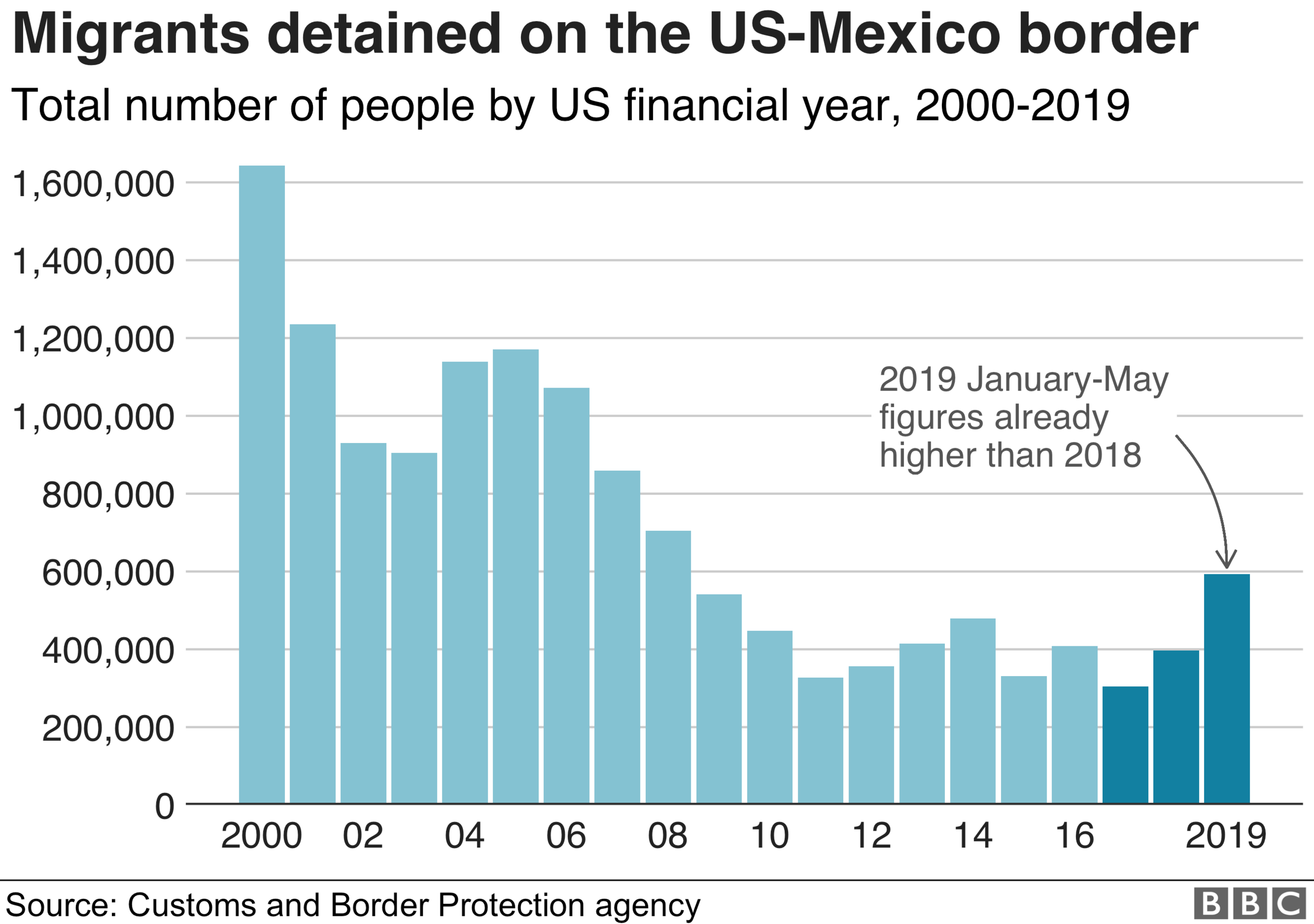

1) Growing migrant numbers

The numbers of people from Latin America seeking protection in the US and being held at the border are rising.

There is not one specific reason why people are leaving Central America and Mexico for the US. But there are a few that are cited regularly.

Reason one: Violence

"We leave our countries under threat. We leave behind our home, our relatives, our friends."

Maritza Flores, from El Salvador, was one of about 1,200 people who travelled in a so-called "caravan" of migrants north through Mexico in 2018, headed for the US border.

"Many people think we left because we are criminals," Ms Flores told the BBC at the time. "We're not criminals - we're people living in fear in our countries. All we want is a place where our children can run free - where they're not afraid to go out to the shops."

"Why I joined Central America's brutal MS-13 gang"

Gang violence is rife in El Salvador and Honduras. According to the most recent UN figures, the two nations had the two highest homicide rates in the world in 2016, external.

Rights groups cite the influence of armed gangs who act with impunity - as well as the targeting of women and LGBTI people - as key factors for the high homicide rates.

Among the most prevalent groups is MS-13, a brutal street gang that started in the US but is now thought to have at least 60,000 members in Central America.

The gang is said to recruit at-risk and poor teenagers and demand they commit murder as an initiation rite, often using a machete. In El Salvador, MS-13 controls entire neighbourhoods.

Over the past few years, there has been a significant increase in the number of people travelling to the US because they fear persecution by gangs like MS-13.

While persecution is not the only reason people from Central America migrate to the US - economic volatility, natural disasters and the desire to join family members have also been cited by aid groups - there is evidence it is a growing factor, and a credible one.

The sound of migrant children separated from parents

People seeking asylum in the US can request a "credible fear" interview if returning home would put their life at risk. An asylum officer then tries to establish if their request is based on a fear of persecution based on race, religion, nationality, political beliefs or membership of a particular group, including a gang.

In the 2012 fiscal year, there were 13,880 credible fear applications. In 2018, according to US Citizenship and Immigration Services, external, there were 99,035 applications, and the vast majority were deemed to be justified in both years.

In 2018, the highest number of credible fear applications came from citizens of Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador. The UN refugee agency says that those three countries have all "experienced a dramatic escalation in organised crime by gangs", external that have turned parts of the countries into "some of the most dangerous places on earth".

Where do America's undocumented immigrants live?

Far from striking down credible fear applications, the Trump administration is granting them at an unprecedented rate. But Mr Trump has been keen to raise the threshold for what counts as "credible fear".

In 2017, the attorney-general at the time, Jeff Sessions, said the system had been exploited, external.

A year later, he issued a ruling that said victims of domestic abuse and gang violence should no longer generally qualify for asylum in the US - although this was eventually struck down by a judge.

But the US isn't the only country to which people are fleeing in large numbers. About 294,000 refugees from north and central America were registered worldwide, external during 2017, an increase of 58% on the previous year.

"We hear repeatedly from people requesting refugee protection, including from a growing number of children, that they are fleeing forced recruitment into armed criminal gangs and death threats," a UN statement said.

As the number of people requesting credible fear interviews has increased, so too has the number of people being detained at the US border.

In May 2019, 144,278 people were held or denied entry while trying to cross the border, external, compared with 51,862 in the same month the year before.

Reason two: Escaping poverty

One UN survey of a group of migrants in January 2019, external again found many were fleeing violence - 68.3% said they had had to change homes due to incidents related to violence or insecurity in the preceding 12 months.

But 68% also said they were moving for better labour opportunities, and 12% for education opportunities.

Countries in Central America are among the poorest in the world while the US is one of the richest, with the world's largest economy (by GDP):

According to the World Bank, close to 60% of people in Honduras live in poverty, external, and in rural areas about one in five people live on less than $1.90 (£1.51) per day

About 59% of people in Guatemala live in poverty, external, while in El Salvador the proportion is 31%

The boy who risked his life for an American dream

President Trump has repeatedly condemned economic migrants, saying two months after he launched his candidacy that "they're taking our manufacturing jobs, they're taking our money." However, many studies say that immigration produces net gains for the US economy.

Those entering the US for a better quality of life are not considered refugees.

However, US and international law currently says that people can seek asylum if they fear persecution at home on the basis of their race, political opinion, nationality, religion or because they belong to a particular social group.

Five more things to read

There's another factor to bear in mind too: climate change. With economies that are heavily reliant on agriculture, Central American countries are particularly vulnerable to changes in temperature and the weather.

A number of recent reports - including a series by the New Yorker magazine, external - have acknowledged the role climate change is already playing in driving people from Central America. But one World Bank report last year said the number of people displaced because of climate change in Latin America could rise, external to 2.1 million by 2050.

2) The main players and their motivation

To understand the zero-tolerance policy on immigration, it helps to understand who is behind it.

When Donald Trump announced his candidacy for the White House on 16 June, 2015, he set the tone for how he would later approach the presidency.

A look back at some of the things Donald Trump has said about Mexicans

"When Mexico sends its people, they're not sending their best," he said. "They're sending people that have lots of problems... They're bringing drugs. They're bringing crime. They're rapists. And some, I assume, are good people."

And so, in early 2018, Mr Trump announced a "zero tolerance" policy to prosecute all adults who try to cross the US-Mexico border illegally, including those who planned to seek asylum in the US.

Mr Trump often cites the dangers of MS-13, which sprung up among Salvadorean immigrants in 1980s Los Angeles and has since spread to at least 46 states. Mr Trump has called them "animals" and threatened to rid the US of their influence.

He has focused closely on immigration since becoming president, repeating many of the same claims he made on the day he ran for office. He has backed proposals to cut the number of legal immigrants to the US by 50% over the next 10 years, and by cracking down on immigration, he is not just sticking to a campaign promise, but playing to his base: his core supporters.

A Washington Post - ABC News poll, external in April 2019 found that 63% of Republicans said they were more likely to support Mr Trump for re-election in 2020 given his handling of illegal immigration.

However, the same poll found that his approach was less popular with Americans overall - with 44% of adults saying his approach made them more likely to oppose him, compared with 31% who were supportive.

Stephen Miller: The man behind Trump's immigration plan

The zero tolerance policy also reveals the influence of one man in particular: Mr Trump's senior policy adviser, Stephen Miller, an immigration hardliner tasked with putting the president's words into actions.

Mr Miller, one of the president's few original aides to keep their job, was the person who put together the ban on immigrants from majority-Muslim countries announced soon after Mr Trump came to office.

The New York Times reported that in April 2018, when it became clear that the number of people being held at the border was growing significantly, Mr Miller pushed for a harder line on immigration.

"It was a simple decision, external," he told the New York Times. "The message is that no-one is exempt from immigration law."

His position in 2019 is even more secure than a year earlier when the border crackdown began, thanks partly to the departure of immigration officials who supported less restrictive policies.

3) The law and the loopholes

Is it legal to separate families and detain children in poor conditions? This question goes to the centre of the debate on immigration and is not as easy to answer as you may think.

Firstly, the policy of family separations at the border - a Trump policy, despite his claims to the contrary - ended after the initial outcry in 2018 with the president signing an executive order, then a judge separately ordering the practice to end.

US migrant children "hungry, dirty, sick and scared" – lawyer Elora Mukherjee

So why are some families still being separated?

The New York Times has reported that 700 families had been separated in the past year, external via "loopholes" in the court order - when parents have a criminal conviction or a disease, or when it is an aunt, uncle, or sibling accompanying the child. Some parents may themselves be under 18 and also detained.

There is also significant debate about the conditions under which people are being kept. This too is because of a lack of clarity in the law.

A 1997 court decision, known as the Flores Settlement Agreement, sets a standard which the US government must follow when it comes to treating migrant children.

But the Department of Justice has sought to amend the agreement to allow it to hold children for longer, and has disputed interpretations of the 1997 court decision - most notably, when a government lawyer argued in June 2018 that the order does not specify that detained children be given showers, soap or toothbrushes.

Justice department says toothbrush and soap 'not required' for migrants

As long as children continue to be separated from their families, the legal challenges from both sides are likely to continue.

But aside from the loopholes and the legal disputes, plain old bureaucracy also appears to be a problem.

Unaccompanied children are by law supposed to be detained for only up to 72 hours. But several reports say many are being kept in detention centres - often in squalid conditions - for much longer, as government agencies struggle to process the vast number of people being held at the border.

"The agents are working their tails off trying to get this squared away," one immigration official told the Washington Post in May 2019, external, "but it's a daily struggle with the amount of people we're encountering."

- Published11 July 2019

- Published26 June 2019

- Published26 June 2019

- Published31 October 2020

- Published18 June 2018

- Published15 June 2018

- Published19 June 2018

- Published23 January 2018