Crossing Divides: Brazil Amazon - Old enemies unite to save their land

- Published

Kayapó and Panará, once rivals, have united against the policies of the Brazilian government

While the world's attention has been focused on the fires raging in the Amazon rainforest in Brazil, indigenous people living there have warned that the policies of President Jair Bolsonaro pose a bigger threat to their existence.

Rival groups have now come together to fight the government's plans for the region that is their home, as BBC News Brasil's João Fellet reports from the Amazon village of Kubenkokre.

Dozens of indigenous people gathered in this remote part of northern Brazil last month after travelling for days by bus and boat.

The meeting brought together formerly sworn enemies such as the Kayapó and the Panará.

The two groups were at war for decades, raiding each other's villages in tit-for-tat attacks. The warring came to a brutal end in 1968, when an attack by the Kayapó, who came armed with guns, left 26 Panará, who only had arrows to defend themselves, dead.

Tensions remained high for years but according to those gathered in Kubenkokre, the two sides have now overcome their animosity for a greater goal.

"Today, we have only one enemy, the government of Brazil, the president of Brazil, and those invading [indigenous territories]," Kayapó leader Mudjire explained.

"We have internal fights but we've come together to fight this government."

His words were echoed by Panará leader Sinku: "We've killed the Kayapó and the Kayapó have killed us, we've reconciled and will no longer fight."

"We've got a shared interest to stand together so the non-indigenous people don't kill all of us," he said, referring to the threats posed by the arrival of miners and loggers carrying out illegal activities in their area.

'69,000 football fields lost'

More than 800,000 indigenous people live in 450 demarcated indigenous territories across Brazil, about 12% of Brazil's total territory. Most are located in the Amazon region and some groups still live completely isolated and without outside contact.

President Jair Bolsonaro, who took office in January, has repeatedly questioned whether these demarcated territories - which are enshrined in Brazil's constitution - should continue to exist, arguing that their size is disproportionate to the number of indigenous people living there.

His plans to open up these territories for mining, logging and agriculture are controversial, and any change to their status would need to be passed by the Brazilian Congress.

Indigenous groups performed traditional dances and songs during the meeting

But it is something that worries the indigenous leaders gathered in Kubenkokre. "Other presidents had more concern for our land. [Mr Bolsonaro] isn't concerned about this, he wants to put an end to what our people have and to how we live," explains Panará leader Sinku.

"That's why I have a heavy heart and that's why we're here talking to each other."

In some demarcated areas, loggers and miners are already at work after some local indigenous leaders granted them permission.

Indigenous leader Bepto Xikrin told the gathering how some 400 miners and loggers had illegally entered the Bacajá territory since the start of the year. He said that members of his indigenous group were scared and did not know what to do.

And according to a network of 24 environmental and indigenous groups, Rede Xingu+, an area equivalent to 69,000 football fields was destroyed between January and June of this year alone in the Xingu river region.

Kayapó leader Doto Takakire shows some of the destroyed areas in the Xingu basin

Heavy machinery has caused major damage and the Fresco and Branco rivers that run through the region have been contaminated with mercury.

Kayapó leader Doto Takakire said illegal mining had been further encouraged by the fact that it often goes unpunished.

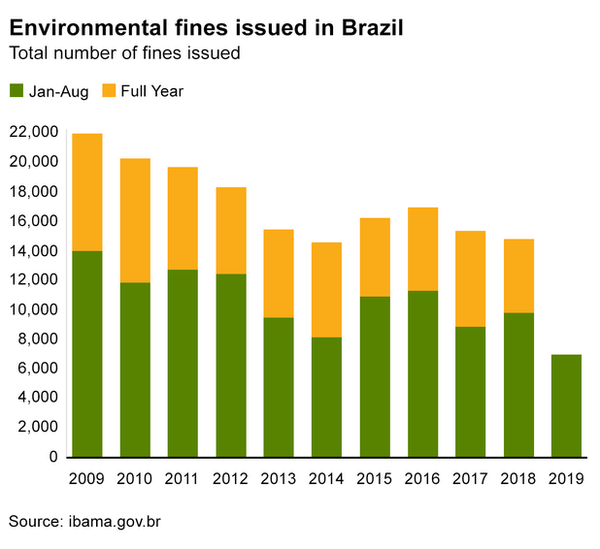

Analysis by BBC Brasil shows the number of fines handed out by the Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (Ibama) for environmental violations has dropped significantly since President Bolsonaro took office on 1 January.

Mr Bolsonaro has in the past pledged to limit the fines imposed for damaging the Amazon and many blame the president for Ibama's current weak position.

'We won't repeat the past'

At the meeting - which was held in both Portuguese and Kayapó - participants discussed projects for their region's economic developments which do not contribute to deforestation, such as handicrafts and the processing of native fruits.

"[I'm concerned] about the trees, water, fish, the non-indigenous people who want to enter our land," explained Sinku. "I don't want to contaminate the water with [toxic products from] mining... That's why I'm here."

Indigenous groups which have allowed miners on to their land were not invited, an omission which some of those attending described as a missed opportunity.

"There's no-one here who wants agribusiness or mining in their villages, so are we just going to talk amongst ourselves?" Kayapó leader Oé asked.

Why the Amazon rainforest helps fight climate change

The fires which have been burning across the Amazon were not a big topic of debate at the gathering, in part because they have mainly happened outside protected indigenous reserves but also because those gathered consider illegal mining and logging as more pressing threats.

"We won't repeat the past," Kayapó leader Kadkure concluded. "From now on, we'll be united."

BBC Crossing Divides

A season of stories about bringing people together in a fragmented world.

- Published13 August 2019

- Published2 July 2019

- Published25 April 2019