Obstacles to Arab-Israeli peace: Jerusalem

- Published

Many armies have come to conquer Jerusalem over the past millennia

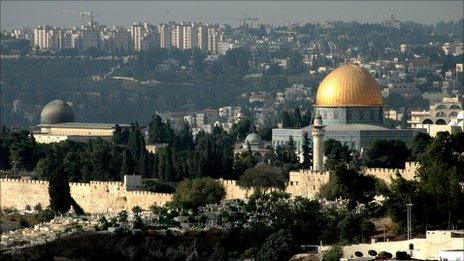

The ancient city of Jerusalem has changed hands many times, its religious significance exerting a powerful pull on Jewish, Christian and Muslim conquerors.

Religious writer Karen Armstrong has observed that those who held it longest are those who showed the most tolerance to devotees of other faiths.

She cites two Muslim leaders - Caliph Omar and Saladin - as exemplars of this approach, and the Crusaders as the city's most blood-soaked ravagers.

More than 40 years ago, Israel's army captured East Jerusalem from Jordan in the June 1967 War.

The area fell in the heat of a deadly battle, but Israel did not massacre its Palestinian inhabitants or destroy its holy shrines like the medieval Christian knights.

From the Jewish perspective 1967 brought the "reunification" of the holy city, restoring a divine plan after centuries of interruption.

But history has yet to decide if Israeli rule over the city is a doomed enterprise, that will founder - on Karen Armstrong's analysis - because of the very measures taken to make Jerusalem Israel's "eternal and indivisible" capital.

Modern fortress

The victory of 1967 and the capture of East Jerusalem was an exhilarating time for Jews, both religious and secular.

Battle-weary Israeli troops ran through the narrow alleys of the Old City to the Western Wall to pray and celebrate.

Under Arab control since 1948, the Jewish holy places had been tantalisingly out of reach to Israelis - in violation of the Israel-Jordan armistice agreement.

Nothing was going to stop the 1967 leaders from creating facts on the ground that made it impossible for Muslim Arabs to reclaim the eastern half of the city.

"We have returned to our holy places... And we shall never leave them," said Gen Moshe Dayan as he stood before the timeworn stones of the Western Wall.

Indeed, a raft of UN resolutions and international conventions outlawing the change of status of occupied territory conquered by military means have had little impact on Israeli thinking.

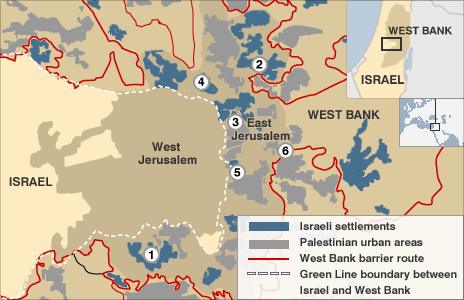

Within days Israel had annexed east Jerusalem, drawn new, greatly expanded municipal boundaries (that cut out some heavily populated Palestinian areas) and demolished an entire Arab quarter of the city in front of the Western Wall, one of the holiest sites in Judaism.

Years of rampant development followed, increasing Israel's presence in East Jerusalem, external. It became a fortress - defended not by walls and ramparts, but by a ring of settlements, blocks of flats and highways.

The architecture is there for all to see, but the diplomatic situation is more complicated.

The international consensus has never recognised Israeli sovereignty in East Jerusalem - the city and its surroundings were designated a corpus separatum by the UN in 1947, to be given a special international status and government.

No country has its embassy in Jerusalem. Even Israel's closest ally, the US, has withstood pressure from Congress to move its embassy from Tel Aviv, insisting the status of Jerusalem should be decided in Israeli-Palestinian negotiations rather than unilaterally.

Precarious lives

The 240,000 Arab inhabitants of East Jerusalem live a strange half-existence, rarely in direct conflict with Israel, but resolutely clinging on to their Palestinian identity and cause.

Allowed special Israeli residency permits, they enjoy advantages over those in the occupied West Bank - but many feel their future in the city is not guaranteed.

Some Palestinian suburbs of Jerusalem, like Abu Dis, are now severed from the city

They say discrimination overshadows their lives: restrictions on building or renovation; disregard by the municipality even though they pay taxes; bureaucratic obstacles if they marry Palestinians from elsewhere; confiscation of their papers; revocation of their residency rights if they take residency or citizenship in another country or spend more than seven years abroad.

Israel has allowed the Palestinians of East Jerusalem to remain, but it has hemmed them in, squeezed them, left them in no doubt the city is no longer theirs.

Meanwhile, hundreds of thousands of Jewish settlers have been allowed, or encouraged, to move to the occupied east of the city - an area the Palestinians hope to establish as the capital of their future state.

Palestinians from outside the city - in the West Bank and Gaza - are rigorously excluded by a ring of roadblocks and Israeli military checkpoints.

They now find themselves experiencing the same sense of deprivation and longing for Jerusalem, and determination to make it theirs again, that the Diaspora Jews once did.

In recent years, Israel has been building the controversial West Bank barrier around Palestinian population centres, a response to the suicide bombings of the 1990s and after 2000.

Around parts of East Jerusalem a massive wall now separates some Palestinian suburbs from the centre of Jerusalem and others from the West Bank.

Many observers see the possibility of disaster in Israel's unyielding pursuit of its policies in Jerusalem.

They argue that resolution with the Palestinians, and the wider Arab and Muslim world, will not be possible without compromise on the holy city.

- Published2 September 2010

- Published2 September 2010

- Published2 September 2010