Obstacles to Arab-Israeli peace: Palestinian refugees

- Published

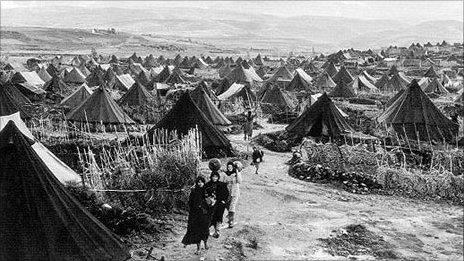

The refugee camps which sprung up in 1948 became permanent residences in exile

More than 60 years after the establishment of Israel, there is no Arab-Israeli issue that remains as utterly divisive as the fate of Palestinian refugees.

In the course of Israel's creation in 1948 and its occupation of the West Bank and Gaza in 1967, more than half the Arabs of pre-1948 Palestine are thought to have been displaced.

Today there are millions of Palestinians living in exile from homes and land their families had inhabited for generations.

Many still suffer the legacy of their dispossession: destitution, penury, insecurity.

Palestinian historians, and some Israelis, call 1948 a clear example of ethnic cleansing - perpetrated by the Haganah (later the Israeli Defence Forces) and armed Jewish gangs.

Official Israeli history, by contrast, says most Palestinian refugees left to avoid a war instigated by neighbouring Arab states, though it admits a "handful" of expulsions and unauthorised killings.

What is undisputed is that the refugees' fate is excluded from most Israeli-Palestinian peace efforts because, given a right of return, their numbers endanger the future of the world's only Jewish state.

The issue of the refugees is therefore seen by many Israelis as an existential one.

Massive displacement

Four million UN-registered Palestinian refugees trace their origins to the 1948 exodus; 750,000 people belong to families displaced in 1967 - many for the second time.

Palestinian advocacy group Badil says another 1.5 million hail from pre-1948 Palestine but were not UN-registered, while an additional 274,000 were internally displaced inside Israel after 1948, and 150,000 were displaced in the occupied territories after 1967.

That makes more than six million people, one of the biggest displaced populations in the world.

Israel steadfastly argues that all refugees - and it disputes the numbers - should relinquish any aspirations to return to what is now its territory, and instead be absorbed by Arab host countries or by a future Palestinian state.

It disavows moral responsibility by arguing that 800,000 Mizrahi Jews were displaced from Arab countries between 1945 and 1956 (most of whom settled in Israel) and insists Palestinians left willingly.

But that view is at odds with UN General Assembly Resolution 194 and Article 13 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Resolution 194 asserts the refugees' unconditional right of return to live at peace in their old homes or to receive compensation for their losses.

Disputed status

Whatever the rights and wrongs of their cause, the practicality of return and questions of moral justice, in Mid-East diplomacy the refugees' fate has been largely ignored.

Palestinians refuse to give up on claims dating back to 1948

This has come about because most resolutions of the Arab-Israeli conflict have been pegged to the 1967 war, while the events of 1948 have been discounted as an element of the conflict.

Israel has deployed a number of arguments to justify blocking the return of Palestinian refugees, such as saying that it is the only Jewish state, the refuge of Jews from around the world, while there are 22 Arab countries where they could go.

It also points out that UN General Assembly resolutions have no force under international law and says the unassimilated refugee population has been held hostage by frontline Arab states waiting for Israel's destruction.

The diplomatic focus on 1967 has been advantageous for Israel: territory occupied at that time is regarded as the entire problem, and solutions can therefore be limited to dividing up that land.

This is problematic for many ordinary Palestinians, however, because it sidelines the Nakba, the "catastrophe" of 1948 - an issue that for them lies at the heart of the conflict.

Demographic prerogative

Palestinians accuse Israel of a kind of "Nakba-denial", absolving itself of liability, but condemning itself to perpetual conflict with its Arab neighbours.

Israel vigorously denies such a characterisation. Zionist historians justify what happened in 1948 by saying the new Jewish state was threatened with annihilation by the invading Arab armies.

But some of Israel's "new", or revisionist, historians argue that its founding prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, exaggerated the Arab threat, in order to implement a pre-determined plan to expel Palestinian civilians and grab as much of the former Palestine as possible.

Demography - the need to have a large majority of Jews to sustain a Jewish state - has certainly been a key concern for Israel since its foundation.

Under a 1947 UN-sanctioned plan to partition Palestine, Israel would have been established on 55% of the former territory, and without a significant transfer of population the Jews in that territory would have scarcely exceeded the Arab population there.

The 1948 war ended with Israel in control of 78% of the former Palestine, with a Jewish-Arab ratio of 6:1.

The equation brought security for Jewish Israelis, but emptied hundreds of Palestinian villages and towns of 700,000 inhabitants - the kernel of the Palestinian refugee problem today.

With the justification of not wanting to jeopardise its Jewish majority, Israel has kept Palestinian refugees and their descendants out of negotiations on a settlement to the Palestinian-Israeli conflict.

But for most Palestinians, their fate remains an open wound, unless there is a Middle East peace deal that acknowledges and makes reparation for what happened to the refugees.

- Published2 September 2010

- Published2 September 2010

- Published2 September 2010