Obstacles to Arab-Israeli peace: Water

- Published

The region supports large popularions on the margins of some of the world's driest deserts

The Arab-Israeli dispute is a conflict about land - and maybe just as crucially the water which flows through that land.

The so-called Six-Day War in 1967 arguably had its origins in a water dispute - moves to divert the River Jordan, Israel's main source of drinking water.

Years of skirmishes and sabre rattling culminated in all-out war, with Israel quadrupling the territory it controlled and gaining complete control of double the resources of fresh water.

Any country needs water to survive and develop. In Israel's history, it has needed water to make feasible the influx of huge numbers of Jewish immigrants.

Therefore, on the margins of one of the most arid environments on earth, the available water system had to support not just the indigenous population, mainly Palestinian peasant farmers, but also hundreds of thousands of immigrants.

In addition to their sheer numbers, citizens of the new state were intent on conducting water-intensive commercial agricultural such as growing bananas and citrus fruits.

Shared water

Israel says the 1967 war was forced upon it by the imminent threat of hostile Arab countries and there was no intention to occupy more land or resources.

But the war's outcome left Israel occupying an area not far short of the territory claimed by the founders of the Zionist movement at the beginning of the 20th Century.

In 1919, the Zionist delegation at the Paris Peace Conference said the Golan Heights, Jordan valley, what is now the West Bank, as well as Lebanon's river Litani were "essential for the necessary economic foundation of the country. Palestine must have... the control of its rivers and their headwaters".

In the 1967 war Israel gained exclusive control of the waters of the West Bank and the Sea of Galilee, although not the Litani.

Those resources - the West Bank's mountain aquifer and the Sea of Galilee - give Israel about 60% of its fresh water, a billion cubic metres per year.

Heated arguments rage about the rights to the mountain aquifer. Israel, and Israeli settlements, take about 80% of the aquifer's flow, leaving the Palestinians with 20%.

Israel says the proportion of water it uses has not changed substantially since the 1950s. The rain which replenishes the aquifer may fall on the occupied territory, but the water does flow down into pre-1967 Israel.

Palestinians say water politics are just part of the injustice of occupation

But the Palestinians say they are prevented from using their own water resources by a belligerent military power, forcing hundreds of thousands of people to buy water from their occupiers at inflated prices.

Moreover, Israel allocates to its citizens, including those living in settlements in the West Bank deemed illegal under international law, between three and five times more water than the Palestinians.

This, Palestinians say, is crippling to their agricultural economy.

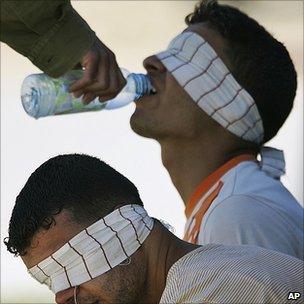

With water consumption outstripping supply in both Israel and the Palestinian territories, Palestinians say they are always the first community to be rationed as reserves run dry, with the health problems that entails.

Fruitless discussions

Not surprisingly, during the era of Arab-Israeli peacemaking in the 1990s, water rights became one of the trickiest areas of discussion.

They were set aside to be dealt with in the "final status" Israel-Palestinian talks, which were never concluded.

Israeli settlement activity continued in some of most sensitive water areas in the West Bank, despite Israel's undertaking not to act in ways that prejudice final status talks.

Stalled negotiations on Syria's dispute with Israel over the Golan Heights - occupied by Israel in 1967 and annexed in 1980 - also foundered on water-related issues.

Syria wants an Israeli withdrawal to 5 June 1967 borders, allowing Syria access to the Jordan and Yarmouk rivers. Israel wants to use boundaries dating back to 1923 and the British Mandate, which give the areas to Israel.

By contrast, the Jordan-Israel treaty of 1994 produced notable agreement on use of wells in the Wadi Araba area in the south and sharing the Yarmouk in the north.

In the 21st Century Israel has tried to solve the Palestinian problem unilaterally, pulling troops and settlers from Gaza and building a barrier around West Bank areas with the largest concentration of Palestinians.

Although Israel says this is a temporary security measure, the barrier encroaches deep onto occupied territory - especially areas of high water yield.

Better future?

Water war has not yet happened but it could yet

Middle Eastern rhetoric often portrays the issue of water as an existential, zero-sum conflict - casting either Israel as a malevolent sponge sucking up Arab water resources, or the implacably hostile Arabs as threatening Israel's very existence by denying life-giving water.

Former UN Secretary General Boutros Boutros-Ghali may not have been right when he said in the 1990s that the next war in the Middle East would be about water not politics, but a future war over water is not out of the question.

Demand for water already outstrips supply, requirements are rising and current supply is unsustainable.

Hydrologists say joint solutions need to be found, because water requirements are interdependent and water resources cross political boundaries.

That necessitates improved conservation and recycling by both sides.

Improving the political atmosphere would allow supplies to be piped from neighbouring countries. Also crucial, experts say, are investment in desalination and other technical advances.

Such solutions are desperately needed in the medium to long term. In other words, Israel and the Palestinians must work together, because they cannot survive as combatants.

- Published2 September 2010

- Published2 September 2010

- Published2 September 2010