Iraq 'bleeding antiquities' as instability continues

- Published

While many ancient artefacts have been recovered thousands may never be found

As the US prepares to withdraw its last combat troops from Iraq, international cultural experts are warning that the country is "bleeding antiquities" and that artefacts representing the world's cradle of civilisation are still in peril.

Precise figures are hard to establish because much of Iraq's art and antiques remains undocumented. In 2003 an estimated 15,000 artefacts were stolen from the Iraqi National Museum and only about a third have been returned.

But experts believe hundreds of thousands more have been looted from the country's archaeological sites that rank among the most important in the world.

"These are fuzzy numbers, but we just don't know. Looters go in privately and they dig. They don't document what they find," says Prof John Russell, a cultural adviser to the US State Department.

"The first time anyone sees these artefacts is when they're seized by the police or turn up through dealers."

One such haul uncovered by customs officers in New York contained dozens of cuneiform tablets, the oldest known system of writing. Until they were found, nobody knew they existed.

They are among 1,054 items discovered in the US alone. Earlier this year, a pair of 2,800-year-old Neo-Assyrian gold earrings from a mass of gold jewellery known as the "Treasures of Nimrud" were among items returned in a special ceremony to the Iraqi Embassy in Washington DC.

"This is an Iraqi problem. The Iraqi people and the Iraqi government should take the first steps and start protecting their cultural heritage," says Dr Donny George Youkhanna, the former director of the Iraqi National Museum.

He fled Iraq during the 2005 insurgency and now teaches at Stony Brook University in New York.

"Iraq's heritage is the wealth of the Iraqi people. It's the memory of the Iraqi people, so they should make more effort to protect this. Every day these sites are bleeding antiquities," he said.

Funding fears

Prof Russell says the worst looting is in southern Iraq, where hundreds of sites have been raided. Large sites such as Isin and Umma now look like cratered moonscapes.

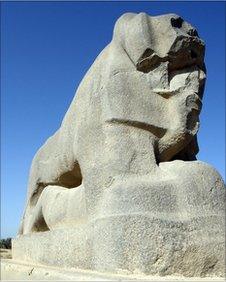

Experts say the military presence in Babylon did irreparable harm

Part of the problem is the ongoing lack of security in Iraq - and once the last US combat troops withdraw at the end of August, the remaining 50,000 soldiers will take on an advisory role, helping to train Iraqi police.

Experts say the future of Iraq's cultural heritage cannot be safeguarded until there is a strong and stable central government with a functioning antiquities department backed by law.

The US government has awarded $13m (£8.3m) to help fund the Iraqi Cultural Heritage Project.

The two-year initiative, which ends in December, has established a Conservation and Preservation Institute in Erbil, a training programme for Iraqi archaeologists and renovated galleries and storage facilities at the Iraqi National Museum.

Although that was reopened briefly in 2009, it remains largely closed to the public because of security issues.

The Iraqi State Board of Antiquities and Heritage has also received more than $1m to help restore the ancient site of Babylon. That was damaged by US troops who established a military camp on the archaeological site, mistakenly believing they were outside the city walls.

It is not clear what will happen when funding for these and other projects ends.

And little is being done to safeguard the future of Iraq's modern art and monuments. Many of these have deliberately destroyed as part of the de-Baathification process aimed at removing symbols of Saddam Hussein's regime.

"There was first the de-Baathification policy… then there was random looting and destruction, and there were things that offended certain religious sensibilities. There was always one reason or another," says Prof Nada Shabout, an Iraqi-American modern art expert who teaches at the University of North Texas.

"Some of the public monuments were in bad taste and were ugly, and I would not be heartbroken if they were brought down. But there is a system of conserving heritage and they were nevertheless part of the history of the country… So do we throw away the baby with the bath water?"

Artists flee

And while public attention and funding has focused on restoring and preserving Iraq's antiquities, there has been less support for the Iraqi National Museum of Modern Art which was also looted during the conflict.

Much of Iraq's modern art has also been looted from galleries in the upheaval

From an original collection of some 8,000 works, Prof Shabout says only 1,500 remain at the National Museum of Modern Art which now shares its space with government departments.

Prof Shabout says many works turn up at well-known auction houses or art dealers, but because records of the museum's holdings were destroyed, there is no way to prove they were stolen.

She has been funded by the American Academic Research Institute of Iraq to compile an online archive based on photographs, memory and research. She now has about 600 authenticated images, but there is a long way to go.

Many of Iraq's established modern artists have moved abroad to escape the conflict and protect their work.

"I wish I could be optimistic but a very important part of history has gone, and little acts of goodness are not bringing it back," says Prof Shabout.