Shaken not stirred: How Yemen president stays in power

- Published

The Yemeni president offered a series of concessions even before the protests began

Among his friends and foes alike, Yemen's strongman President Ali Abdullah Saleh is best known for the ability to manoeuvre his way out of trouble.

For 32 years, he has stayed on top of Yemen's unforgiving political game, often by buying off tribal leaders or playing them against each other.

His presidency has so far survived a secessionist movement in the south, rebels in the north and active al-Qaeda presence, but in the wake of demonstrations in Egypt and Tunisia, Mr Saleh faced an entirely new challenge - the anger of his own people.

"When Tunisia happened Saleh was annoyed. When Egypt happened, he was horrified," says Sanaa-based political commentator Abdul Ghani al-Iriyani.

As Yemenis prepared for their own "Day of Rage" on 3 February, Ali Abdullah Saleh went for a pre-emptive strike and offered the opposition a number of significant concessions.

He promised new economic incentives, a national dialogue, pledged that he would step down in 2013 and would not let his son inherit power.

The tactics worked. The demonstration, although the biggest in Yemen's recent history, was peaceful and brief.

'Unlikely reformer'

The opposition called for radical reform instead of resignation and said they were willing to give the president his last chance to reform.

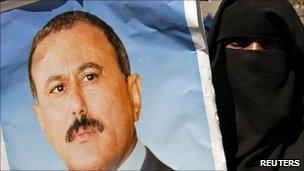

Down but not out - but Yemen's president still has many loyal supporters

"So far everything that we've heard are just words, but we are waiting for action, we are waiting for him to deliver," says Yassine Naman, the leader of Yemen's opposition socialist party.

Mr Naman says this is the first time in decades that the country's fragmented opposition has gained an upper hand in dealing with the president. "He is the weakest he's been in a long time," he said.

But Ali Abdullah Saleh still has plenty of weapons in his arsenal.

"Constitutional reform, electoral reform, real dialogue with the opposition, redistribution of some of the wealth," lists Mr al-Iriyani. "There is a lot that President Saleh can give people and the opposition while still staying strong."

The problem is that the very nature of the political system that Ali Abdullah Saleh has created makes him an unlikely reformer.

Yemen's most effective political institution is a tribal network of patronage, in which tribal leaders and sheikhs offer the government loyalty in exchange for protection and, often, financial incentives.

Even some of the opposition leaders are part of this system. The system gives the president some room for manoeuvre in the short term, but makes him vulnerable in the long run.

In order for Mr Saleh to deliver real economic change and ease people's lives, he would have to take from the elite, but this could cause the entire system to collapse.

"Saleh's presidency is hanging off ropes - each rope is a military or a sheikh who is keeping him in power. If they start cutting the ropes, he will fall," says Mr al-Iriyani.

People's discontent in the meantime is on the rise. Half of Yemen's 23 million already live below the poverty line. Unemployment is at nearly 40%, the country is running out of oil and water and corruption is rampant.

Pushing hardest for change are the young, many of whom feel that they have no future in Yemen. But while the economic situation is worse here than it is in Egypt, it will be much more difficult for the young to bring their anger out into the streets.

Fragmented opposition

Internet in Yemen is available to only about 200,000 users. And women, who constitute nearly half of the population, are unlikely to play a real role.

"I am fed up, there is nothing here apart from poverty and corruption," says Hala, a 23-year-old student I met in an internet cafe in Sanaa. But she is not about to take her anger to the streets. This isn't Egypt, she says, in Yemen, a woman's place is at home.

"Our tradition won't allow us to go out, but men have a lot of freedom here," she says.

For the first time in decades, some are putting this freedom to use.

"Remember Mr President, this country's isn't for you, it's not for your family, this country is ours. So get out, leave us alone," one student activist told me.

Without internet, without women, and with the political opposition fragmented and so far reluctant to back them, the odds of Yemeni students bringing real change are very small indeed. But, for the first time in decades, people are speaking out here.

"Egypt changed everything. People have woken up," says Abdul-Bari Taher, a well-known Yemeni writer and a journalist who spent much of his life in opposition to the president. "This is the beginning of the end of Saleh."

Mr Saleh may not be going anywhere yet, but he has already lost his once absolute monopoly on power.

- Published4 February 2011

- Published3 February 2011

- Published3 February 2011

- Published28 March 2011