Why Saudi rulers feel under siege

- Published

King Abdullah's legacy is, in Saudi terms, reform-minded, but his heirs may reverse even this

The Arab Spring has seen seemingly indomitable leaderships toppled and a mass call, particularly among young people, for reform. Its fallout has left the leaders of Saudi Arabia feeling under siege, as Middle East analyst Roger Hardy explains.

Consider how the world looks to Saudi Arabia's frail and aging ruler, King Abdullah.

Enemies lurk everywhere. The Arab Spring has unleashed forces which no-one can control, and from which no Arab state is immune.

Iran is deemed to be stirring every pot, from Lebanon to Bahrain.

Neighbouring Yemen is increasingly unstable - and plays host to a branch of al-Qaeda which threatens Saudi security.

Barack Obama's America is seen as betraying the Saudi kingdom in its hour of need.

Saudi Arabia, in short, is under siege - and King Abdullah's instinct is to batten down the hatches.

Echoes from the past

In some ways, Saudi rulers have been here before.

In the 1950s and 1960s, a wave of Arab nationalism emanating from Egypt swept over the Middle East - threatening the pro-Western monarchies such as the House of Saud with destruction.

Saudi women will soon be allowed to vote, although they remain banned from driving

Then, too, the kingdom felt encircled by hostile forces.

Then, too, petro-dollars and Western support were weak tools for fending off trouble.

Not that oil wealth does not sometimes come in handy.

One of King Abdullah's responses to the Arab Spring has been massive hand-outs to keep his people sweet.

Moreover, the kingdom has more reason than ever to use cheque-book diplomacy in a bid to win friends and influence people throughout the region.

But such measures may not be enough.

If money could buy the kingdom's way out of trouble, its position might be less precarious.

But, with the exception of tiny Bahrain, its influence is limited.

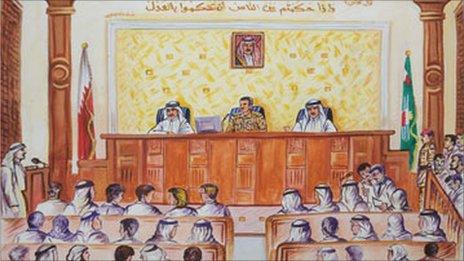

By intervening in Bahrain, with money and troops to crush a Shia insurrection, the king sought to protect one of his flanks - and shore up his defences against what he sees as undue Iranian influence.

But in the longer run, Saudi intervention may make things worse - adding to the sense of grievance among the Bahraini opposition and needlessly escalating tension with Tehran.

An uncertain legacy

The king seems conscious of his own mortality.

He wants to leave Saudi Arabia in better shape than when he found it - which explains his promise to Saudi women that they will eventually get the vote.

He may be an unlikely reformer but he is, in Saudi terms, a reformer nevertheless.

He has never shared the severely puritanical view of Islam of his country's Wahhabi religious establishment.

But his legacy is uncertain.

The two senior princes next in line to the throne - his half-brothers Sultan, the defence minister, and Nayef, the interior minister - are distinctly less reform-minded.

They might be willing to sacrifice women's rights for the sake of appeasing religious conservatives.

That would be dangerous.

Young Saudis, like young Arabs everywhere, want change. Like their counterparts in Tunis and Cairo, they want jobs and dignity and greater freedom of expression.

Sealing off Arabia - returning it to the isolation of the past - is not an option.

Roger Hardy is a visiting fellow at LSE's Centre for International Studies.

- Published16 December 2013

- Published28 September 2011

- Published25 September 2011

- Published21 July 2011

- Published28 June 2011

- Published25 September 2011

- Published4 October 2019