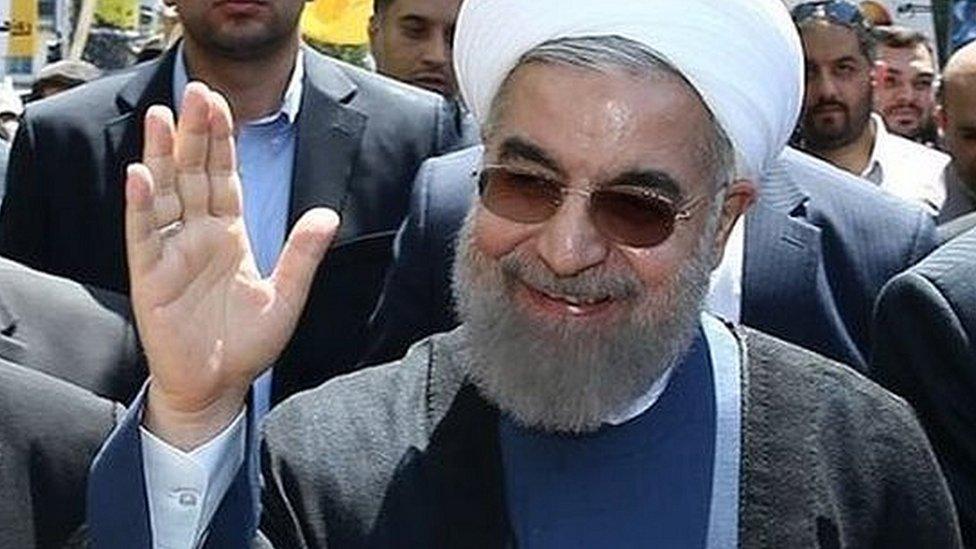

Hassan Rouhani and Iran's nuclear opportunity

- Published

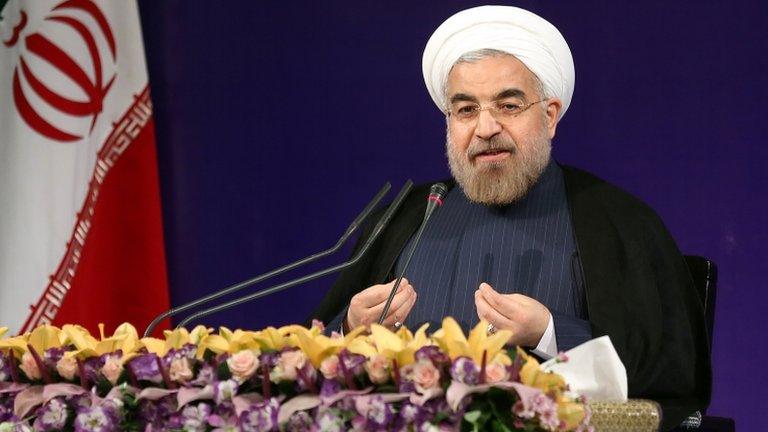

Hassan Rouhani says the dispute should be resolved through greater transparency and mutual trust

The surprise victory of Hassan Rouhani in Iran's Presidential election has prompted widespread hopes of an opportunity for progress in resolving the tensions over Iran's nuclear programme.

Often described as "a moderate" - though perhaps "centrist" might be a more adequate label in terms of Iranian politics - President Rouhani's victory is seen as marking a more pragmatic turn; a desire on the part of many Iranians for their bread and butter issues to be addressed.

Resolving the nuclear dispute could open the way to a lifting of the sanctions against Iran that have had an impact on its economic performance. So does Mr Rouhani's election offer the hope of progress?

How much authority will he really have to change policy in Tehran? And are other countries - especially the United States - willing to respond to any Iranian initiative?

Experts agree though that whatever the obstacles to a deal, this is a moment that must be seized by all sides.

"It may very well be the last best opportunity," says Trita Parsi, founder of the National Iranian American Council.

"The two sides have been in deadlock in the past few years, but now prospects for an opening exists."

That's a view shared by Mark Fitzpatrick, of the Non-Proliferation and Disarmament Programme at the International Institute for Strategic Studies in London.

This, he says, "is a unique time when both sides appear ready to engage. In the past, usually when one has been ready to talk seriously, the other wasn't. Both Washington and Tehran are now looking to find progress through diplomacy."

Iran's decision-makers

But Mark Fitzpatrick remains cautious.

"On President Rouhani's part, despite his pleasant words, it is not even clear if he has the backing from the supreme leader to engage with Washington bilaterally," he says.

"For even an interim solution Iran will have to accept significant limits to its enrichment programme.

"Washington for its part would have to accept some degree of enrichment in Iran and a lifting of some portion of the economic sanctions - well beyond what has been tabled so far."

Iranian Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, still wields much power

Some critics of the idea of an opening say the man with power to decide the nuclear issue remains Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

Trita Parsi, however, argues that the election showed Ayatollah Khamenei is not all-powerful.

"The balance of power within Iran's political elite as a result of the elections is shifting towards greater flexibility" he says.

"But it can only continue to shift in that direction if the West matches that flexibility. Neither side can resolve this issue on their own.

"I believe Obama wants to reach a deal. The question is if he is willing to expend the political capital needed to get that deal and if he can convince Congress, Israel and Saudi Arabia not to spoil the diplomatic process."

Critics say Mahmoud Ahmadinejad's radical presidency isolated Iran

Israeli position

Israel's government has been the least ready to view Mr Rouhani's election as offering any chance of an opening. Trita Parsi - an expert on the tangled relationship between Israel and Iran, explains it this way.

"Israel's quick dismissal of Rouhani revealed Prime Minister Netanyahu's strong desire to see Rouhani for what he wants him to be - a continuation of hard-liner Mahmoud Ahmadinejad's radicalism that made the campaign to isolate Iran seem almost effortless - rather than the change Rouhani actually might represent. In a nutshell," he says, "Netanyahu's approach to Rouhani is that only his actions should matter, not his words. Unless, of course, Rouhani says something provocative. Then the focus should be on his words, not his actions."

Iran has always wanted to tackle a much broader strategic agenda with the Americans. But how much of an appetite is there in Washington for this?

Mark Fitzpatrick says: "There are various matters outside the nuclear issue that Washington would be ready to take up, such as Afghanistan and common issues of concern like narcotics trafficking. But Washington will certainly not accept Iran's proposal to discuss the situation in Bahrain.

"At some point Iran will have to be accepted as a legitimate player in the region and be included in discussions about the Palestine peace process and Syria, for example. Given Iran's support for military groups and for President Assad and the prevailing distrust on both sides, that's not going to be easy."

So how would life be breathed back into a process that has largely been on hold pending the Iranian election?

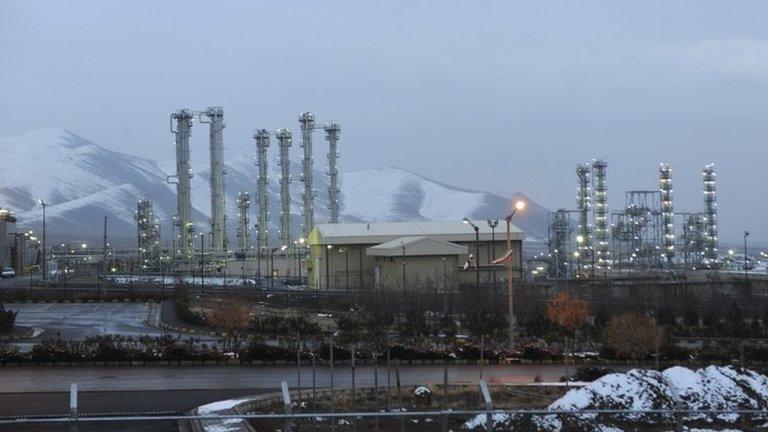

A plutonium reactor near Arak is due to start irradiating uranium by mid-2014

Timing questions

"President Rouhani first has to get his team in place and to see his cabinet ministers approved by the Majlis [the Iranian parliament]," says Mark Fitzpatrick.

"[The Iranian president] needs to name a chief nuclear negotiator and presumably the new team will require some time to undertake a policy review. If they are going to make the kind of compromises that are necessary, they will need to give it some serious thought and build internal consensus, including by persuading Khamenei to overcome his distrust of the US."

Time, however, is not necessarily a commodity in plentiful supply.

"There may be limited time before the expansion of Iran's nuclear programme," Mark Fitzpatrick says.

"Israel is again speaking about military strikes. In Washington there's concern about Iran's nuclear programme next year reaching 'a point of critical capability', meaning that it would be able to make a spurt to obtain a nuclear weapon before there was time to detect this and prevent it.

"Iran's plutonium reactor adds to the time-line pressure. Once it begins irradiating uranium, which is scheduled for mid-2014, the radiation danger of bombing it puts the military option beyond consideration. The date of the Arak reactor going online will present a deadline for a diplomatic breakthrough."

Mr Fitzpatrick says he is not optimistic about a breakthrough. But, he adds, "for the first time in many years, there is a window of opportunity."

- Published6 August 2013

- Published14 July 2015

- Published25 November 2014

- Published20 May 2017

- Published2 August 2013

- Published21 July 2013

- Published6 April 2013

- Published20 March 2013