Inside Jordan's fight against home-grown extremism

- Published

Frank Gardner visits Jordan's border with Iraq

On Jordan's bleak, windswept border with Iraq there is little two-way traffic these days.

The convoys of articulated lorries that used to thunder through the Karama crossing, shuttling goods between Baghdad and Aqaba, have dwindled to a trickle.

On the Iraqi side is Anbar province, where the jihadists from the Islamic State (IS) group have seized towns and large tracts of territory and where a suicide car bomb detonated near the border in late April.

To the north-west lies Jordan's tense border with Syria, and a plethora of competing armed groups.

Rich pickings

"We are facing at least three different armed groups on the Syrian side," says Gen Tawfiq al-Tawalbeh, who until last Sunday was head of Jordan's Public Security Directorate (PSD) and the man tasked by King Abdullah II to shore up the country's internal security.

"In the far west we face al-Nusra Front [linked to al-Qaeda], then in the middle there is the Free Syrian Army, beyond that there are the soldiers of the Assad regime. So we face a lot of threats, a lot of challenges."

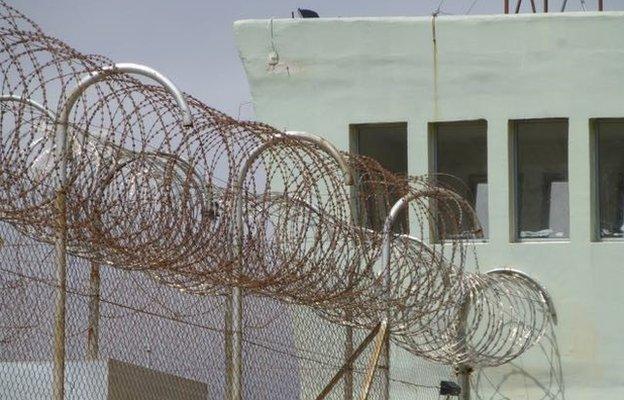

Traffic through Jordan's desert border with Iraq has slowed to a trickle, hurting trade

Since the advance of IS in Iraq and Syria, border patrols have been stepped up

Most of those threats are invisible and lie deep inside Jordan itself.

Unlike the oil-rich Gulf Arab states, this is not a rich country. Jordan has few natural resources and high unemployment amongst the young.

In this overwhelmingly Sunni Muslim kingdom, overcrowded backstreets in towns like Maan, Zarqa and Rusaifa have become hotbeds for Salafist extremists.

The late Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, the forefather of Islamic State, came from just such a place.

IS and al-Nusra recruiters have found rich pickings for their cause here: more than 2,000 young Jordanians have left for Syria to join proscribed terrorist groups.

De-radicalisation programme

Most have not returned, but the dozens who have have found themselves arrested, put on trial and handed lengthy prison terms.

Those suspected of being hardcore, unreformed jihadists end up in high-security wings. But those who can convince the authorities they have turned their backs on extremism are put into a de-radicalisation programme.

"We don't want them to feel they are branded as outlaws," says Lt Col Faris al-Rashid from Police Special Branch.

"So we chose a form of words that won't offend. We call it the Community Peace Centre and it went operational on 1 January this year with the first 69 prisoners".

Al-Rumaimain prison, near Salt, houses more than 500 inmates, including convicted jihadists

In fact, it is more of a programme than a centre. Like similar efforts in Saudi Arabia and the UAE, it uses the power of religious argument by government-approved scholars to try to convince extremists that violence unsanctioned by the ruler is wrong.

After several requests, I was allowed to meet one of the prisoners now going through the programme.

He is being held at al-Rumaimain jail, a short drive out of Amman into the hills.

They call it a "correctional facility" here, but it is still basically a prison with armed and helmeted guards on the gate.

"Abdullah" was not his real name - he did not want his identity to be revealed, partly, I suspect, to save his family from shame. His story is a salutary one.

Persuaded by a friend to drop out of his university degree course to go and fight in Syria, he tried to join the al-Nusra Front but he ended up with IS.

After just two weeks of basic training and indoctrination with the jihadists in north-east Syria he became disillusioned.

Inside Al-Rumaimain prison near Salt - the BBC crew were told they were the first foreign journalists to be allowed in

"I thought I was going to be defending Muslims from the Nusayris," he said, using a derogatory term for President Bashar al-Assad's Alawite sect, "but when I saw Muslims fighting Muslims I decided I had to escape."

He crossed the border into Turkey where after several phone calls home his father persuaded him to come back to Amman.

But Jordan takes a very tough stance on anyone going to join proscribed groups and he was arrested and tried on his return and to his horror, given a lengthy prison sentence.

"I thought that if I went home the authorities would be lenient. I only spent two weeks with [IS], I was just a young guy who had been brainwashed. But instead they gave me five years in prison for joining an armed group, which is too much for me."

Enlisting the public

Abdullah is still hoping for some sort of pardon from the king, but current events are not in his favour.

Jordan is formally at war with IS after it burned to death one of its downed pilots in January.

Since then, opinion in much of the country has swung from being lukewarm about Jordan joining the US-led coalition against IS to being right behind it.

Western diplomats in the region fear it could be only a matter of time before IS hit back with an attack inside Jordan.

The Public Security Directorate call centre can handle up to 25,000 calls a day from the public

Just as in the UK, a part of the country's counter-terrorism strategy involves enlisting the public's help.

Inside the headquarters of the Public Security Directorate in Amman is a giant police call centre linked to CCTV and automated number plate recognition systems around the kingdom.

Staffed by policemen and women around the clock, it takes up to 25,000 calls a day from the public, though most are non-terrorism related.

Jordan is getting a lot of technical help behind the scenes from British counter-terrorism agencies.

But it has also developed its own mobile phone app, called "Jordan Knights", so young Jordanians can report any suspicious sightings.

"We want to improve our tools to meet the language of the new generation," says Col Rashid from Jordan's Special Branch. "So this application... can be easily used to report any single information by text or by recording or by voice message or by taking a snapshot and sending it to us".

Fear of attack

The PSD also has a large number of human informants and even in the cafes of Amman one sometimes has the sense that there are eyes everywhere.

Internal security is clearly a top priority for the government.

It is now 10 years since the last big terrorist incident here, when al-Qaeda in Iraq sent suicide bombers to blow up hotels in Amman, and enormous efforts have been made since then to plug the gaps in security.

But Jordan has some difficult factors working against it: poverty in some quarters, high unemployment, the influx of 1.4 million Syrian refugees, and the fact that two of its neighbours are at war.

Given the upheavals across this region, some fear Jordan will not stay immune from that violence indefinitely.

Photos by Frank Gardner