Will Iran nuclear deal make the Middle East a less safe place?

- Published

Iran called the deal an "historic agreement" - Israel said it was an "historic mistake for the world"

The international negotiators who agreed the Iranian nuclear deal took their talks right down to the wire.

Then - time after time - they moved the wire and kept right on talking.

But in large parts of the Middle East, where the prospect of a stronger Iran is viewed with dread, there was never any real sense of suspense.

Israel, Saudi Arabia and the other states who feel threatened by the terms of the new deal have been resigned for months to the idea that the US-led world powers were determined to have an agreement and were prepared to offer major concessions to get one.

Israel's Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who sees Iran as a mortal enemy, has already said that the agreement shows the dangers of being ready to do a deal at any price, and the Sunni Arab states of the Gulf, who see Iran as a dangerous and aggressive neighbour, will also feel that a much, much harder bargain could have been struck.

An Israeli minister, Danny Danon, put it in lurid terms.

"This agreement is not just bad for Israel, it's dangerous for the entire free world. Giving the world's largest supporter of terrorism a free pass in developing nuclear weapons is like providing a pyromaniac with matches," he said.

'Funds for guns'

The Vienna negotiators have had to keep in mind a complex cocktail of issues - not just Iran's atomic energy programme and the suspicion that it is planning to develop nuclear weapons.

There are related questions, too, which worry Iran's rivals in the Middle East almost as much.

An end to sanctions will help Iran fund its proxy militias, like Hezbollah

The easing of restrictions on financial transactions which are part of the international embargo will give Iran extra economic muscle.

That will mean more funds - and more guns - for the proxy armies it funds around the Middle East, like the Shia militias of Iraq, and Hezbollah, the Lebanese military force which is helping to prop up Iran's ally Bashar al-Assad in Syria.

That is likely to reinforce Iran's view of itself as the champion and defender of Shia communities wherever they are found and to push the Sunni kingdoms of the Gulf - led by the Saudis - into responding in kind.

The conflicts raging around the Middle East in places like Iraq and Syria can be viewed as part of a growing confrontation between followers of the two main traditions in the Islamic world - Sunni and Shia.

Giving Iran access to more money and more weapons may well serve to intensify that confrontation.

'Outmanoeuvred'

Sceptics around the Middle East fear that the US-led negotiators in Vienna were no match for the negotiating skills of the Iranians.

The result, they say, is an Iran which has engineered a kind of rehabilitation into the international community without being asked to compromise on its self-image as a revisionist power in the Middle East, an exporter of revolution.

There is a sense in the Middle East that the international negotiators were weak in part because they were divided.

Sceptics fear Barack Obama was determined to reach a deal, even at a heavy cost

So the United States might be aware of the fears of its ally Israel that Iran will use its extra financial resources to buy more sophisticated weapons for Hezbollah to aim at Israeli cities.

But China and Russia are keen to start exporting weapons to Iran again - seeing it as a valuable customer.

The Iranians have been able to exploit those differences on the opposite side of the table.

And there have been fears in the Middle East about the attitude to the talks of Barack Obama.

Is this an American President in search of his own "Nixon-in-China" moment - the signature foreign policy achievement which will define a historic legacy?

Rehabilitating Iran would fit the bill nicely - as long as it can be done safely, of course.

A senior diplomat in the Gulf put it to me in these words: "Let's just agree that the search for a legacy doesn't make us stronger."

Like-for-like

Israel has been more strident on the matter because it sees Iran as an existential threat - and because Iran has threatened to wipe it off the map.

It has unhelpfully unearthed a few video memories from the mid-1990s when US-led negotiators appeared confident they had managed to defuse the nuclear ambitions of another international pariah state, North Korea.

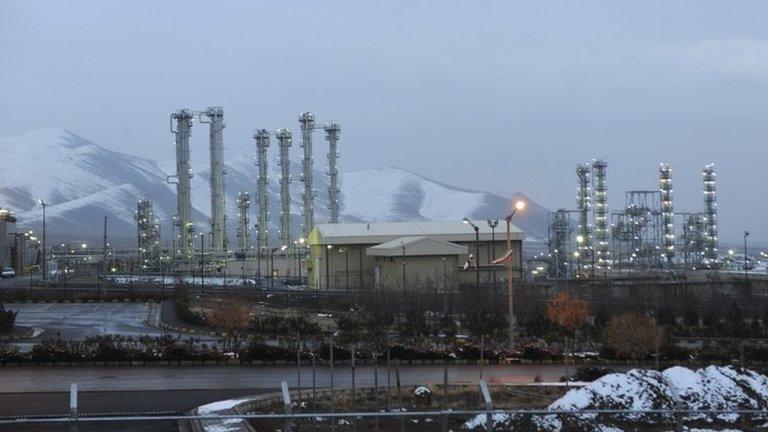

Saudi Arabia has said it will seek the same rights as Iran, fuelling fears of a potential nuclear arms race

That is a reminder that while the diplomats negotiating on behalf of the global powers may sincerely believe they have made the world a safer place, they may also be wrong about Iran, as the Clinton administration was about the North Koreans.

Iran's enemies remain of the view that the Iranians are hell-bent on acquiring nuclear weapons at some point and have merely agreed to a delay in return for a variety of short-term concessions.

There is a danger now that Saudi Arabia will feel that a nuclear-capable Shia state must be matched by a nuclear capability in the hands of the Sunni states too.

That brings the nightmare of a nuclear arms race in the Middle East a step closer.

And it leaves open the question of how Israel will respond. It already has a nuclear capability of its own, although its policy is never to acknowledge or discuss it.

Military option?

The Israelis have plenty of allies on Capitol Hill and they may now try to rally Congressional sceptics to undermine White House attempts to sell the deal in Washington.

That strategy does risk worsening the already sour relationship between Mr Obama and Mr Netanyahu, but the Israeli prime minister may calculate that that is a price worth paying.

And ultimately, of course, a deal which Israel considers to consolidate Iran's status as a threshold nuclear power puts the issue of unilateral Israeli military action back on the table.

Israel says it reserves the right to use military force to prevent Iran from getting a nuclear bomb

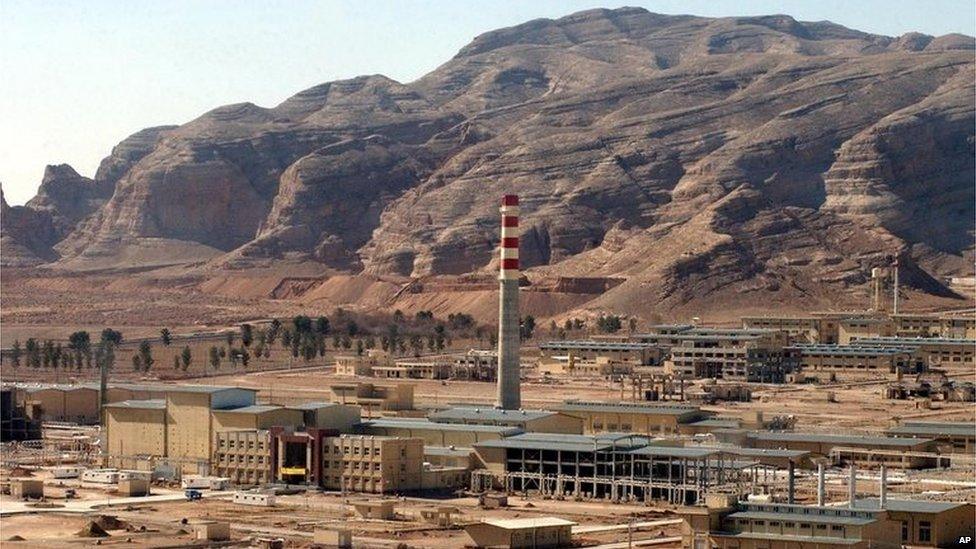

Would Israel consider air strikes to degrade Iran's nuclear infrastructure?

Israel could argue that its persistent threat to launch such an attack helped to create the pressure that led to the Vienna talks. The issue has been on the back burner in recent years as sanctions have been given time to work and the Vienna negotiations gathered momentum.

But one source familiar with Israeli intelligence thinking told us that Israel was still committed to the Begin Doctrine - the idea that a state pledged to the destruction of Israel could not be allowed to acquire the means of destruction.

The Obama administration will find the nuclear deal a tough sell to its allies in the Middle East like Saudi Arabia and Israel - even if it sugars the pill with upgraded weapons shipments.

But as the battle to get the deal past Congress begins, plenty of thought is being given across the Middle East to the difficulties and dangers that lie ahead.

- Published14 July 2015

- Published14 July 2015

- Published14 July 2015

- Published28 June 2015