Should anyone ever talk to IS?

- Published

The so-called Islamic State (IS, also known as Isis and Isil) now controls vast swathes of Iraq and Syria and has affiliates which have claimed to have carried out attacks in countries including Tunisia, Egypt, Libya and Nigeria.

IS today is more brutal, more sophisticated, and more powerful than many predicted. And military action so far has had only limited success in pushing it back. So some have suggested a different approach: negotiation. Some find the idea of talks abhorrent - others say it's time to at least consider it.

Four experts spoke to BBC World Service's The Inquiry about their views on the question: should anyone ever talk to IS?

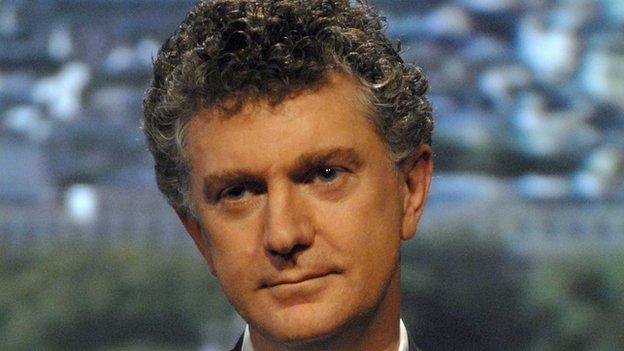

Jonathan Powell: Time to talk?

Jonathan Powell was chief negotiator on Northern Ireland for the British government under Tony Blair.

"If you want to destroy the Islamic State, you're not going to be able to do it from the air. And no one in the West seems prepared to put boots on the ground. So there is no military strategy for destroying Isis. There needs to be a political strategy. In my view, that would involve talking to them.

"All terrorists are barbaric. That's why they're terrorists, because the only thing they have in common is that they use the tool of terror.

Jonathan Powell: There needs to be a political strategy. In my view, that would involve talking to them

"[Isis] use their violence for a very obvious purpose. They use it to frighten their opponents so they run away. They know that if they kill one Western aid worker, one Western journalist, in a horrific way, they will get a huge amount of publicity. Yes, of course the violence they use is abhorrent, but that doesn't mean to say the lessons we've learnt from dealing with previous terrorist groups all fall away.

"We talked to the IRA, not because they had guns but because they had a third of the Catholic vote. If you were dealing with a group that has almost no political support, such as Baader-Meinhof... you're not going to need to negotiate because there isn't a political question at the heart of the matter. And it seems to me likely that there is a political question at the heart here in Syria and Iraq.

"If the conflicts I've looked at over the last... 30 years are anything to go by, and if Isis have political support, then we will end up speaking to them. Maybe they'll fade like snow in the spring, but there is very little historical precedent for that happening in this sort of circumstance.

"It's my hypothesis that there is such political support. And the idea of extreme Islamists, whether Al Qaeda or Isil, seems to have enough robustness in it that there is a problem we're going to have to address politically at some stage, not simply by force of arms."

But, Powell says, there are two caveats: you don't stop fighting, and you don't begin those talks now. You prepare the ground, by establishing a basic conversation.

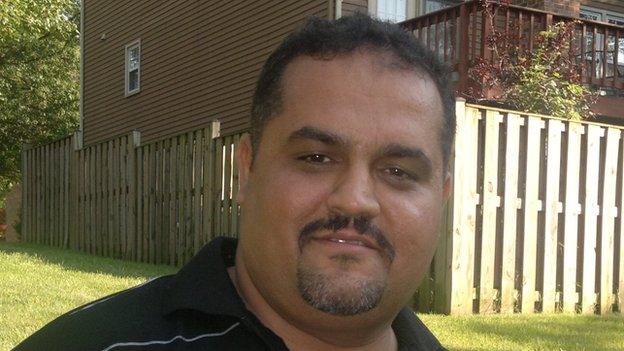

Qais Qasim: A view from Baghdad

Qais Qasim is a journalist living in Baghdad. Over the past year, he's been following the story of IS, talking to those who've fled from the towns and villages they control.

"They are not a political group, they are a criminal group. They use suicide attacks and explosives instead of words. They have no political demands.

"Isis is not a Sunni movement any more. They get in fights against Sunni tribes. The fight against Isis is not a part of the conflict between Sunnis and Shias. Isis is not based on sectarian philosophy but it's based on a certain way [of looking at] human life and they think they have the ultimate right to decide who live[s] and who die[s].

Qais Qasim: You cannot negotiate with savages like Isis fighters

"I cannot find anybody here in Baghdad who is willing to talk to Isis. Nobody [is] willing to give Isis the legitimacy. And if it happens, they will consider it a sign of weakness from the Iraqi security forces.

"People here in Baghdad are very optimistic about the Iraqi forces and the rebuilding of the Iraqi forces."

"It's not the time, and it won't be any time, to talk to Isis today and tomorrow and even after five years because they are criminals. You cannot negotiate with savages like Isis fighters. You cannot let a criminal get away with his crime."

Mina al-Oraibi: Divide and talk

Mina al-Oraibi is assistant editor-in-chief at Asharq Alawsat, a London-based Arabic newspaper.

"I come from Iraq, my father's home town is Mosul. So of course I care about it from a personal point of view. I also care about it because I think what will happen in the fight against Isis inside of Iraq will determine much of what will happen in the Middle East and the Arab world.

"I don't believe that it's time to speak to those that are within the top echelons of Isis because there's not much to talk about there, they've made that very clear.

Mina al-Oraibi: We've fallen into the trap of treating [Isis] almost like it is one strong group

"There are different groups that have come under the fold of Isis in different countries, whether it's in Iraq or in Syria or otherwise that are there for either political gain or because they felt that they were pushed into a corner where they had no other military option. Those are the people that are worth speaking to.

"We've fallen into the trap of treating it almost like it is one strong group. And that's actually been a propaganda win for Isis that many of us who would say that we are against them have enabled. And I think it's very, very important to look at those divisions and inferences and be able to pull people back.

"There are still army generals from Saddam's army who are sitting either in Amman or in the Kurdish region of Iraq or in Turkey, not even [in] parts of Isis but they're just sitting around given no role. You know some of these army members have connections and would be able to say 'These are the people I can count on, bring them in.'

"Some Iraqis refer to those that are from the provinces controlled by Isis as terrorists. So it's very important to build that trust and so to tell Sunnis that 'we realise that you are victims of this'.

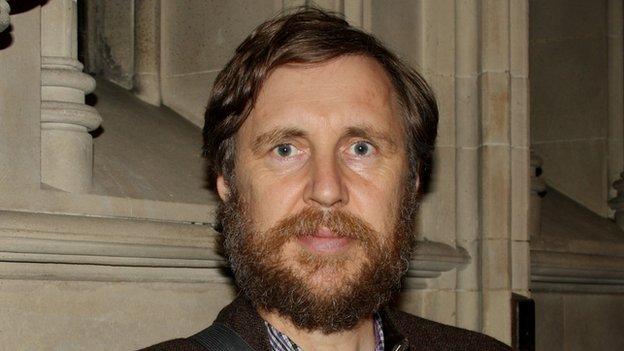

Michael Semple: The long game

Michael Semple worked in Afghanistan for 18 years, as an aid worker, for the EU and the UN. He was one of only a few who were involved in talks with senior Taliban members.

Michael Semple sees a possibility of dialogue on humanitarian issues

"I think somebody who proposed political talks now would be considered foolish from both sides. I don't think IS would buy it, I don't think that the countries of the region or the United States would buy it.

"And yet there are very important humanitarian needs and I think it is time... to see who in Islamic State... is prepared to engage on humanitarian issues and make things a little bit better for now.

"[IS is] big enough, robust enough that it looks as if it's going to be around for quite some time to come, therefore it has structures which I think would be capable of engaging in dialogue... making undertakings which they could subsequently adhere to. But also, because it looks like it's going to be around for quite some time, the price of ignoring them goes up all the time.

"It comes down to the question of whether a humanitarian dialogue... does legitimise the parties involved in that dialogue and, through legitimising them, essentially strengthen[s] them. Now many people... have concluded that it is possible to conduct a humanitarian dialogue without legitimising the parties involved.

"There are regionally-based intermediaries, people who've got some reason to have dealings in areas where IS has a presence. Now quite often it has been religious leaders, sometimes it's business people, traders. I think these are the kind of figures we'd expect to see, long before diplomats.

"I think that the dialogue would have to be worthwhile in its own terms... not with respect to the hope for some eventual political progress. Relationships and confidences which have been built up during that humanitarian dialogue. Later on they might be put to work when the time is right for some kind of political engagement."

The Inquiry is broadcast on the BBC World Service on Tuesdays at 12:05 GMT/13:05 BST. Listen online or download the podcast.

- Published2 December 2015

- Published22 May 2015