Syria war: Hunger stalks besieged Madaya

- Published

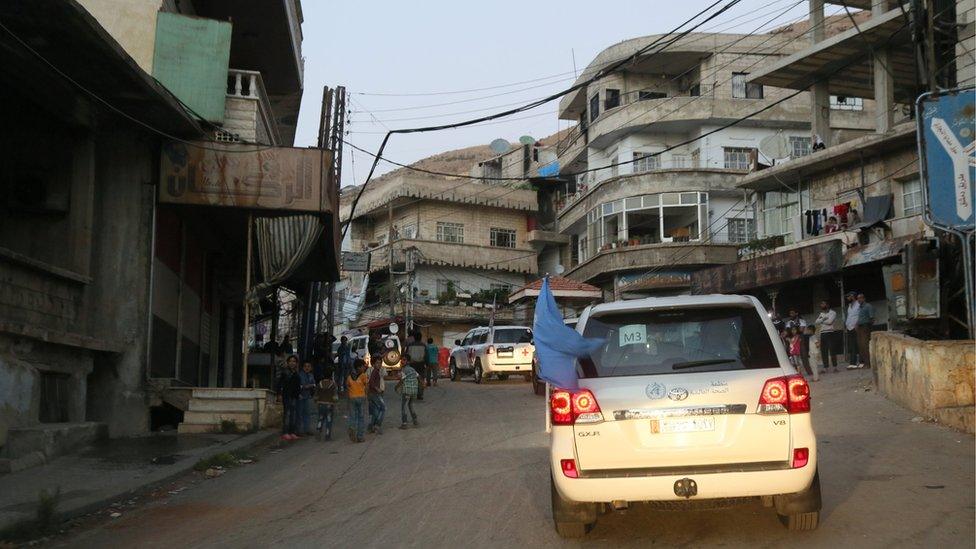

Aid got into Madaya last week for the first time since April

In the basement of a house in the rebel-held Syrian town of Madaya is what people there call a medical centre. It is, actually, just a room with a bed, where the sick come for some help.

But for many of the cases brought in, there is not much that can be done, aid groups say, with what little equipment there is in a precarious state and insufficient medicine available.

In the dim and crowded surroundings, aid workers who went there recently met a woman whose daughter spent four days without eating. This, the mother told them, was because the girl's body no longer tolerated rice.

Residents, under siege since June 2015, said rice had been the only food available there for months.

Some children could no longer walk straight, the workers heard, because they lacked vitamins. Others had stopped growing. Elderly people looked fragile and much older than their years.

The 40,000 residents of Madaya, in the mountains 15 miles (25km) north-west of Damascus, are surrounded by the Syrian army and allied fighters from Lebanon's Hezbollah movement.

Most of their food provision is dependant on infrequent humanitarian deliveries.

Relief finally came last week, when a convoy of 71 trucks brought food, medical supplies and hygiene kits for Madaya and three other besieged cities: nearby rebel-held Zabadani, and government-controlled Foah and Kefraya, in Idlib province, to the north.

It was the first time aid was allowed in in almost six months.

People gather in a makeshift clinic in Madaya

Ingy Sedky, an aid worker with the International Committee of the Red Cross, which was part of the convoy, said she found people looking pale and weak.

Children complained of severe headaches, she added, caused probably by the lack of food.

"They need more protein, vegetables, fruits," Ms Sedky told the BBC from the capital, Damascus.

"There is no meat or milk. They are eating only rice."

Shops in Madaya have remained largely closed and food is scarce

There was international outrage earlier this year after the UN said there were credible reports of people dying of starvation in Madaya.

Children, UN staff were told, were collecting grass with which to make soup, despite several having been hurt by landmines that encircle the city.

A report by the group Physicians for Human Rights, external said 65 people died of malnutrition and starvation in Madaya between the start of the siege and July this year.

Things this time were not as dire, said Mirna Yacoub, deputy representative for the UN's children's charity Unicef in Syria, who was also part of the aid convoy.

"There wasn't the level of acute malnutrition, starvation, like in January," she said, speaking also from Damascus.

"But they are malnourished, there is a severe lack of vitamins. They don't have protein."

Not only the young were weak.

Miscarriages increased, Ms Yacoub added, because women were unable to keep their pregnancies.

Caesareans were also more common because of the poor health of pregnant women - some were so weak they could not go through normal labour.

"They are really suffering. And I really don't know how they're performing C-sections there," she said.

"The operation theatre is just a room, they lack equipments and medicine."

Alcohol used for sanitising equipment had run out and tools were being sterilised using flames. There was also no medical gel for ultrasounds, so a doctor told her he had been using hair gel instead.

Many children in Madaya are malnourished, aid workers say

Chronic health conditions and infectious diseases had gone untreated because of a lack of medicine and specialised care - aid groups said the only people left in the clinic were two dentistry students and a veterinarian.

"People came around us and asked: 'Are you the doctors?'," Ingy Sedky, from the Red Cross, said.

"They thought doctors were coming to help them. They were desperate to have someone helping them."

Earlier this year, Unicef said, seven people diagnosed with meningitis were evacuated for treatment. Two other cases were confirmed in this latest visit, and aid groups are working to take them out too.

Some parents, scared of having their children infected, avoided sending them to school, the UN fund said.

But the pain in Madaya is not only physical.

Residents gathered to welcome the convoy carrying food and medicine

People have shown signs of psychological problems, such as depression, charities helping Madaya's residents say - and the cases go largely untreated.

A report by Save the Children last month said there had been 13 suicide attempts, external in July and August, the youngest a 12-year-old girl.

Ms Yacoub, from Unicef, said: "There was [an attempt by] a mother-of-five who said she couldn't feed and care for the children, and a student who couldn't go to school anymore.

"They just can't cope anymore. They don't know what will be next. When this is going to end.

"One woman told me: 'Death is going to be better than this'."