Yemen conflict: The UK's delicate balancing act

- Published

Saudi Arabia has yet to accept responsibility for the attack

Appalled by the carnage of last Saturday's double bombing of a Yemeni funeral, Britain is sending its Minister for the Middle East on a sensitive mission to Riyadh.

The explosions killed at least 140 people, mostly civilians, and injured over 500.

More than four days on since the attack - which was widely reported to have been an air strike by the Saudi-led coalition - the Saudi authorities have yet to publicly accept responsibility.

The UK, which has a long-standing and lucrative defence and trade relationship with Saudi Arabia, has taken the unusual step of requesting "oversight" of the ongoing investigation into the attack.

Will this be enough to dampen the growing condemnation of US and British military support for the Saudi campaign? Unlikely.

More than 500 people were injured in the attack

Tobias Ellwood MP, the Foreign Office minister for the Middle East and the man who has to periodically stand up in Parliament to defend Britain's arms sales to the Saudis, is due to hold sensitive talks with Saudi Arabia's Foreign Minister Adel Jubair as well as the Yemeni president and the UN Special Envoy for Yemen.

At stake is more than just an explanation of how such a horrific death toll was incurred in a single attack at the weekend.

For the UK, this is also about the whole nature and rationale of its controversial strategic alliance with Saudi Arabia, which campaigners want immediately curtailed.

Unsuccessful war

In March 2015 Saudi Arabia went to war in Yemen at the head of a coalition of 11 countries.

Its aim was to reverse the takeover of the country by Houthi rebels, who are supported by Saudi Arabia's regional rival Iran, and to restore the UN-recognised President Abdrabbuh Mansour Hadi and his government to power.

Armed with state-of-the-art US and British warplanes and their munitions, Saudi Arabia's air force and its allies have complete air superiority in the skies over Yemen, meaning they alone can carry out air strikes.

Saudi Arabia's warplanes and munitions are supplied by the UK and US

These have failed to dislodge the Houthis from the capital Sanaa and from much of the heavily-populated west of Yemen.

The damage inflicted on civilians has been catastrophic. The UN blames the air strikes for causing 60% of the estimated 4,000 civilian deaths.

The Houthis are far from blameless. They and their allies among the forces loyal to the ousted Yemeni leader Ali Abdullah Saleh are accused of shelling densely populated areas, laying mines indiscriminately and contributing to the humanitarian crisis that now afflicts the country.

They have also embedded themselves in the civilian population, exposing non-combatants to the risk of attack.

Saudi Arabia is trying to dislodge Houthi rebels from the capital Sanaa

Round after round of peace talks have failed to reach a compromise deal between the Houthis and the legitimate - but now deeply unpopular - Yemeni government which clings to a corner of land around the southern port of Aden.

Ceasefires have been announced, and then quickly fallen apart.

War crimes?

The Foreign Office is at pains to point out that Britain is not a part of the Saudi-led coalition.

But the fact is that British and US military hardware is sustaining the Saudi campaign and Yemenis know it. The US also provides intelligence and refuelling for the coalition.

Even before Saturday's bombing of the funeral hall there were accusations that Saudi Arabia's air strikes in Yemen constituted a breach of the Geneva Convention and were possibly war crimes.

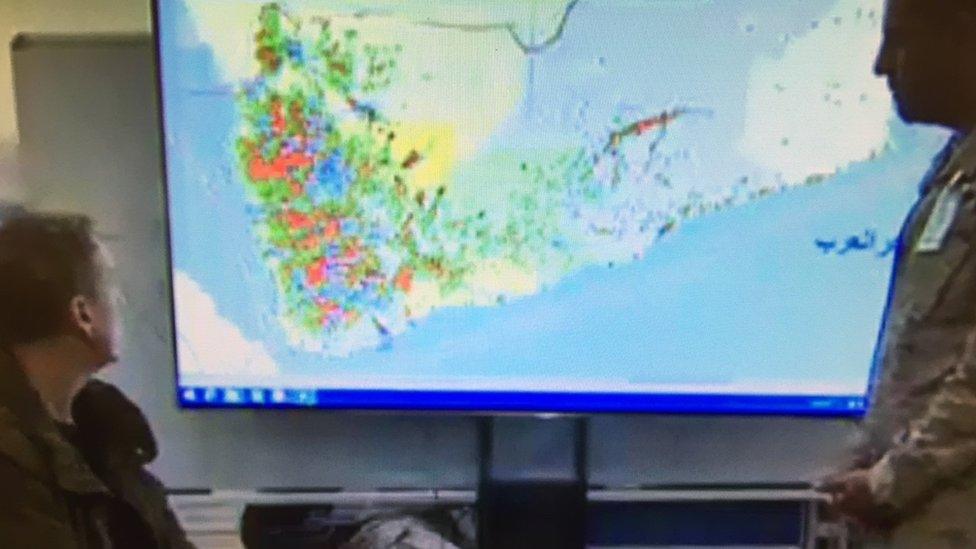

The Saudi-led coalition is run from the King Salman airbase in Riyadh

A Saudi officer shows the BBC's Frank Gardner a map of "no strike areas" in Yemen

The Saudis insist they abide by a strict code, the Law of Armed Conflict, and have never deliberately targeted civilians, a claim disputed by many Yemenis.

The Saudis also undertake to investigate allegations that its warplanes have killed civilians through an 11-nation body called the Joint Incidents Assessment Team (JIAT).

'Criminal judging his own crime'

And hereby lies the problem. The Saudis say the JIAT operates to exactly the same high standards as similar investigations carried out by US and other Western militaries. Although the JIAT has admitted to some targeting errors, several of its members are the very same countries that are part of the Saudi-led coalition.

Hence the jibe on social media that their findings carry as much weight as "a criminal judging his own crime". Hence Britain's request to have what it calls "oversight" (the Saudis prefer to call it "assistance") into this latest incident.

Some of the victims from Saturday's attack. Yemenis know Saudi Arabia uses UK and US military hardware

Defence Secretary Sir Michael Fallon has said if it transpires that civilians were knowingly targeted last Saturday then the UK "could review" its defence relationship with Saudi Arabia.

The Saudis have promised total transparency. That, in theory, should reveal who, if anyone, gave the order to bomb the funeral, knowing that senior Houthi rebel leaders would be present, and crucially whether or not they knew that large numbers of civilians would be hit.

The Foreign Office minister's talks on Thursday could be uncomfortable for all sides.