Saving Syria's heritage: Archaeologists discover invisible solution

- Published

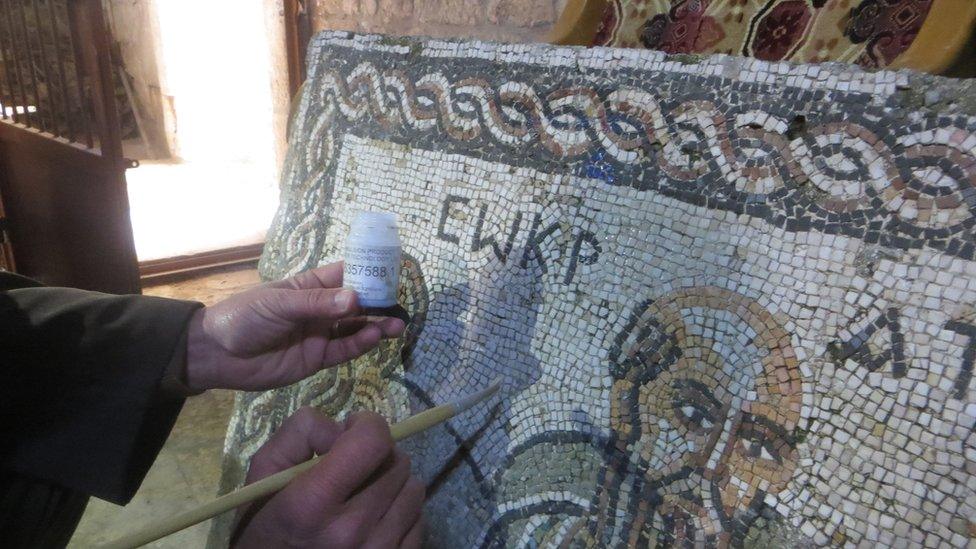

An ancient mosaic is painted with an invisible liquid that is detectable under ultra-violet light

The recent plundering of priceless artefacts from Syria and Iraq by both terrorists and criminal gangs has taken place on an unprecedented scale.

Stolen items have been turning up in Europe and the US, where they have then been offered to private collectors.

The UN heritage body Unesco says the illicit trade is worth millions of dollars.

But an innovative solution may now be at hand which enables archaeologists to trace precious artefacts.

Working in secret, in areas outside Syrian government control, Syrian archaeologists have begun painting some of the country's most valuable artefacts with a clear, traceable liquid.

The solution is invisible to the naked eye, but detectable under ultra-violet light.

The technology was developed by Smartwater, the British crime prevention firm, and was tested by scientists at Reading University and Shawnee State University in the US.

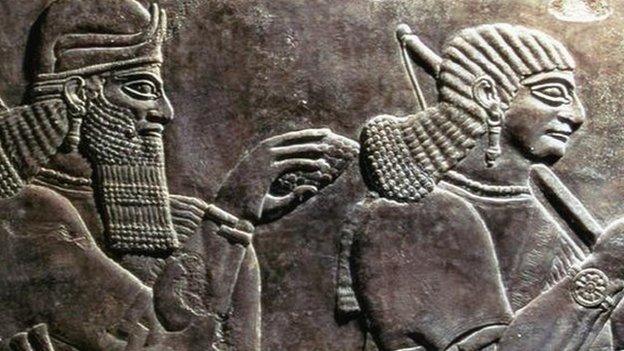

The liquid can be used to trace artefacts such as Byzantine pottery and sculptures

Roman mosaics, Byzantine pottery and ancient sculptures are all being treated with the liquid in a desperate race to stop Syria's heritage being plundered by terrorists and criminal gangs.

The hope is that it will deter both collectors and smugglers of stolen items with the threat of prosecution, since each artefact bears a unique, identifiable code.

The project has been overseen by a renowned Syrian archaeologist, Professor Amr Al-Azm.

He told the BBC that the Smartwater tracing material, which has been designed not to harm ceramics and other ancient materials, was delivered to Turkey in January and then shipped across the Syrian border a month later.

Referring to the fact that so far it is only being used on artefacts in areas outside Syrian government control, Professor Al-Azm said that "Syria's cultural heritage is under threat wherever it is," adding: "This is something that unites us."

But is it a case of too little too late?

After six years of conflict, much of Syria's treasure has already been looted by so-called Islamic State (IS) militants, working with smugglers and criminal gangs.

According to Unesco, the smuggling of valuable artefacts out of the Middle East ranks as one of the major global illicit industries, alongside arms, drugs and human trafficking.

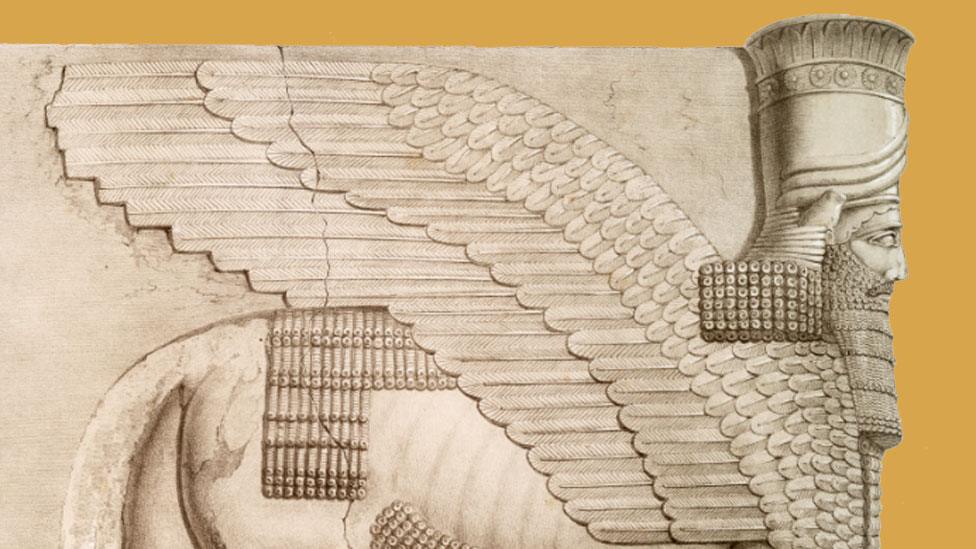

An Assyrian sculpture is recreated after the plundering by IS fighters of the city of Nineveh

A large but unknown quantity of artefacts have been turning up in Europe and the US, where middlemen try to sell them to private collectors.

Iraq, which has suffered a similar problem of looting, has yet to see the project extended across its borders.

The plundering by IS of such iconic sites as Nineveh, near Mosul in northern Iraq, has been well documented, with the jihadists carrying off everything they could sell and smashing up whatever they were unable to move.

Still, Professor Al-Azm is hoping that word will soon spread, amongst smugglers and collectors alike, that handling the region's stolen heritage could end in a criminal prosecution.

- Published29 February 2016

- Published18 November 2016

- Published18 February 2015

- Published6 March 2015