Will Trump's Palestinian policy work?

- Published

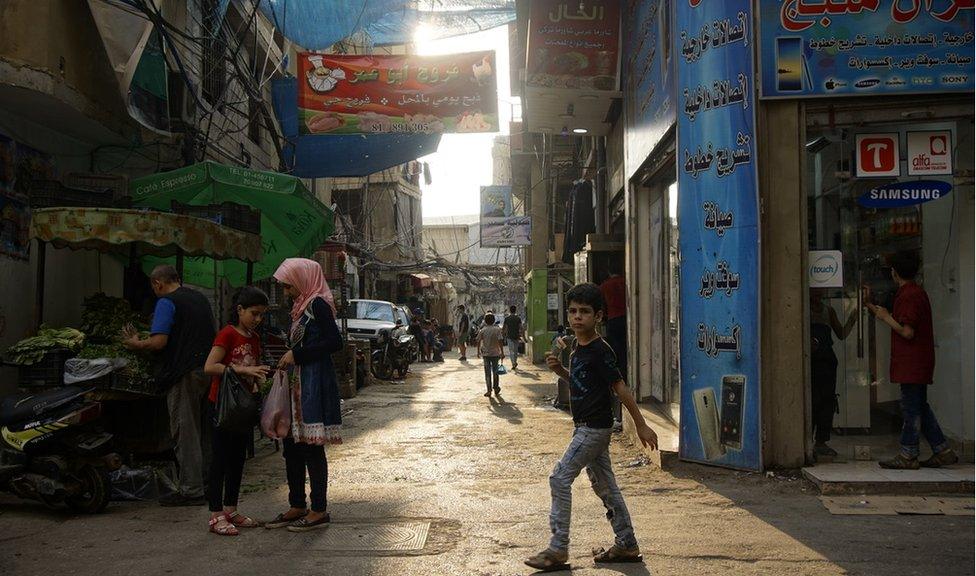

Bourj el-Barajneh has been home to refugees since 1948

"I want to say to Mr Trump that however much he talks about the 'deal of the century', Palestine will stay Palestinian."

Liliane Samrawi, doesn't know what "Palestine" looks like. Neither does her father. Both were born in Bourj el-Barajneh, a Palestinian refugee camp next to Beirut airport.

"I'm 22 years old, and I don't know anything about my country."

But ask Liliane where she is from, and she does not hesitate.

"I'm from al-Kabri."

The village no longer exists. Or rather, the place on the map where it once stood is now a kibbutz (also called Kabri), east of the Israeli city of Nahariya.

It has been 70 years since al-Kabri was part of British Mandate Palestine.

In 1948, 750,000 Palestinians fled or were driven from their homes in the fighting that surrounded the creation of the State of Israel.

Only around 40,000 "1948 refugees" are still alive. The UN says they and their descendants now number more than 5 million.

Cash blow

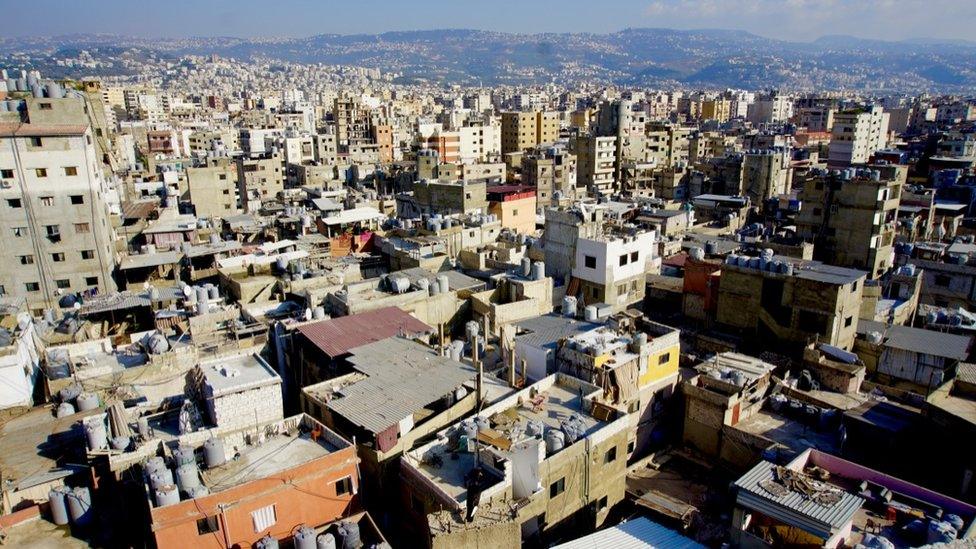

Bourj el-Barajneh has evolved, from a cluster of tents in the countryside to a densely packed, impoverished Beirut suburb.

The camp has evolved into a densely packed metropolis

A spider's web of water pipes and electrical cables, wound together in lethal proximity, now spreads across the camp, obscuring the streets below.

Now the refugees who live here fear Donald Trump is trying to make them disappear altogether.

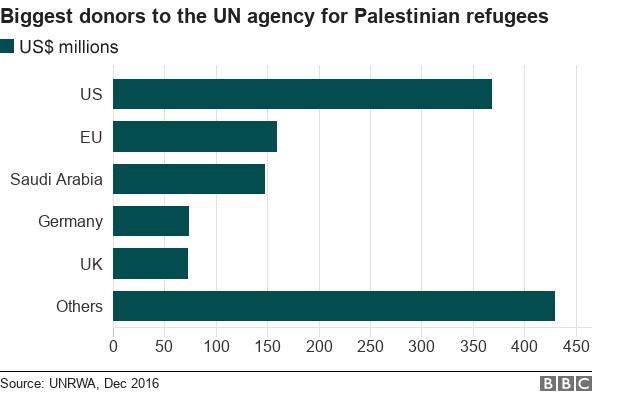

In August, Washington ended its financial contribution to the UN Relief and Works Agency (Unrwa), which has been looking after Palestinian refugees since 1949.

The cut of $350m amounted to around a third of Unrwa's annual budget. Other donors have made up some of the deficit, keeping the organisation's head above water, at least for now.

Explaining the move, President Trump's ambassador to the UN, Nikki Haley, accused Unrwa of crying wolf and playing politics with the number of refugees.

"Every year they come and say 'the schools aren't going to open'," Mrs Haley said, "but they keep adding numbers of refugees to where we're never going to be able to sustain it."

Who counts as a refugee?

The US has not said how many refugees there should be, but questions whether descendants should be eligible.

Unrwa officials reject the criticism.

The BBC’s Paul Adams went to a camp in Beirut to meet the Palestinian refugees who still can't go home

"Unrwa does not inflate the number of refugees," the organisation's Lebanon director, Claudio Cordone, says.

Unrwa says 469,000 Palestine refugees are registered in Lebanon, but that only about 270,000 actually live there.

Lebanon has never granted citizenship to the refugees. They are not allowed to own property or work in 36 specified professions, including medicine, law and engineering.

Over decades of unrelenting hardship, many refugees have left the country, pursuing new lives abroad.

But the UN says that doesn't change who they are.

"Our definition of refugees is in fact in line with the general understanding of what is a refugee in the world. The UN High Commissioner for Refugees recognises descendants of refugees, and we follow exactly the same principle," says Mr Cordone.

Palestinians say they will never give up their claims

The organisation says it is trying to avoid closing schools and clinics, but wage freezes and layoffs have already caused unrest among staff, including one-day strikes in the Gaza Strip.

"Unfortunately… we're bearing the brunt of political decisions that have little to do with our humanitarian mission," Mr Cordone says.

Counter-productive?

The Trump administration's move against Unrwa follows a series of steps this year that have inflamed Palestinian opinion and generally pleased Israel.

In May, the US moved its embassy in Israel from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, which fuelled protests and violence along the fence which separates Israel from the Gaza Strip. Israeli soldiers shot and killed 58 Palestinians. Israel says the soldiers acted in self-defence.

In September, the Trump administration closed the Washington DC offices of the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO), arguing that the PLO was refusing to engage in negotiations with Israel.

At the same time, US officials said the administration's long-awaited Middle East peace plan, dubbed "the deal of the century", would soon be unveiled.

' Palestinians will become even more resistant' - Sari Hanafi, sociologist

Is the Trump administration attempting to bludgeon Palestinians into submission?

"It's so clear that the Americans just want to put pressure on the Arab countries and Palestinians to make concessions," says Sari Hanafi, a Palestinian sociologist at the American University of Beirut.

He says he thinks the tactic will backfire.

"The Trump administration put the Palestinian issue into crisis, and this will translate into much more resistance and a more vivid Palestinian identity," he says.

In Lebanon, which offers the refugees no alternative, that identity still burns with fierce intensity.

- Published1 September 2018

- Published30 January 2018

- Published17 January 2018

- Published16 January