Egypt justice: Freedom by day, prisoner by night

- Published

Samhi Moustafa (centre) has to sleep at a police station every night

Every day, Samhi Moustafa makes a gruelling round trip of 200km (125 miles) between his family home near Cairo and Bani Sweif, a province to the south.

On one such journey, he was seriously wounded in a car accident, but knew he had to carry on. His daily ordeal is compulsory for at least the next five years.

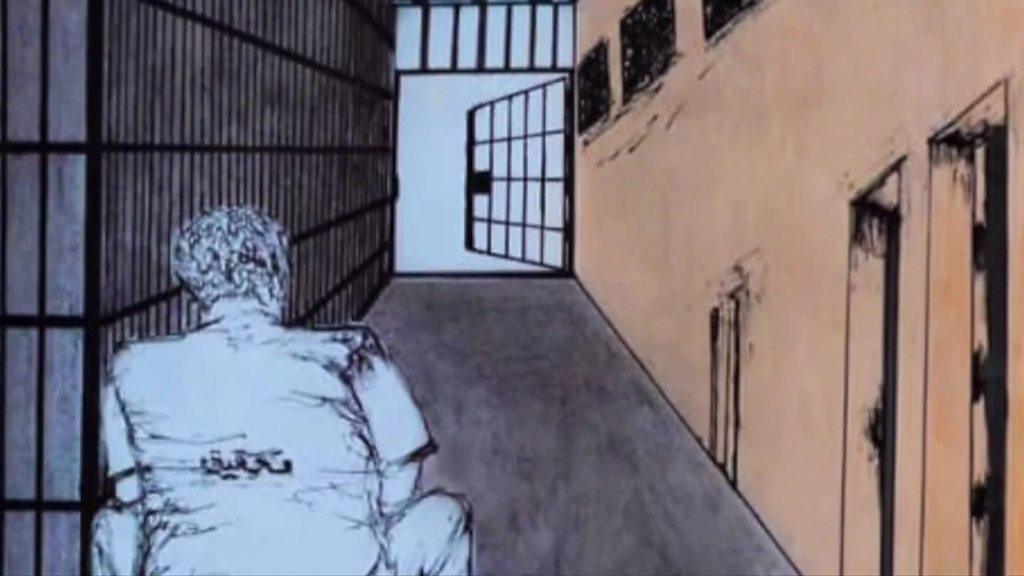

Samhi must spend 12 hours a day at a police station - known in Egypt as a supplementary penalty. He has already served a five-year prison sentence, which ended last year.

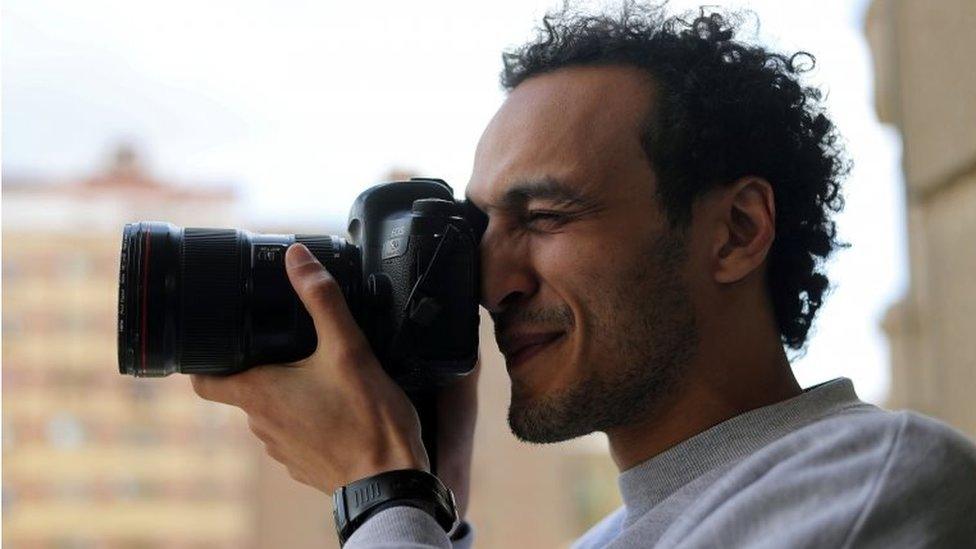

The 32-year-old journalist was convicted of spreading "false news" and helping the now banned Muslim Brotherhood group during a 2013 sit-in in Cairo to protest the ouster of the elected Islamist President Mohammed Morsi.

Samhi denies the charges, and says he was just doing his job.

Samhi, who posted a photo of his wrecked car on Twitter, has since been sentenced to one month in jail in absentia for breaking probation conditions the day of his accident.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

His case is not alone. Hundreds of political activists face similar restrictive probation rules, which human rights groups have condemned as excessive.

BBC News contacted the Egyptian interior ministry for comment but did not receive a response.

Dusk till dawn

Outside a Cairo police station in the early hours of the morning, Rami, dressed in shabby clothes, appeared subdued.

"I can't work, I can't have a family life, I'm bankrupt," he says.

Rami - not his real name - is required to be inside the station every day between 6pm and 6am for the next three years.

Like Samhi, he has already served time in prison - three years - for taking part in an unauthorised protest in 2014.

Rami, who is in his mid-20s, was expelled from college immediately after his imprisonment and his family now has to support him financially.

"This police probation has devastated my life," he says.

Probation conditions differ from one police station to another.

Rami says he is not even given a police cell and instead spends 12 hours in an outside area attached to the station, where he struggles to sleep under the stars.

He has to bring a packed dinner with him every day, and is only allowed access to books, not electronic devices.

Photojournalist Shawkan is among those subject to the strict probation measures

In some police stations, those under probation are allowed to bring blankets from home for sleeping inside small designated cells. In other cases, they are left in the backyard of the walled police station, monitored closely by CCTV.

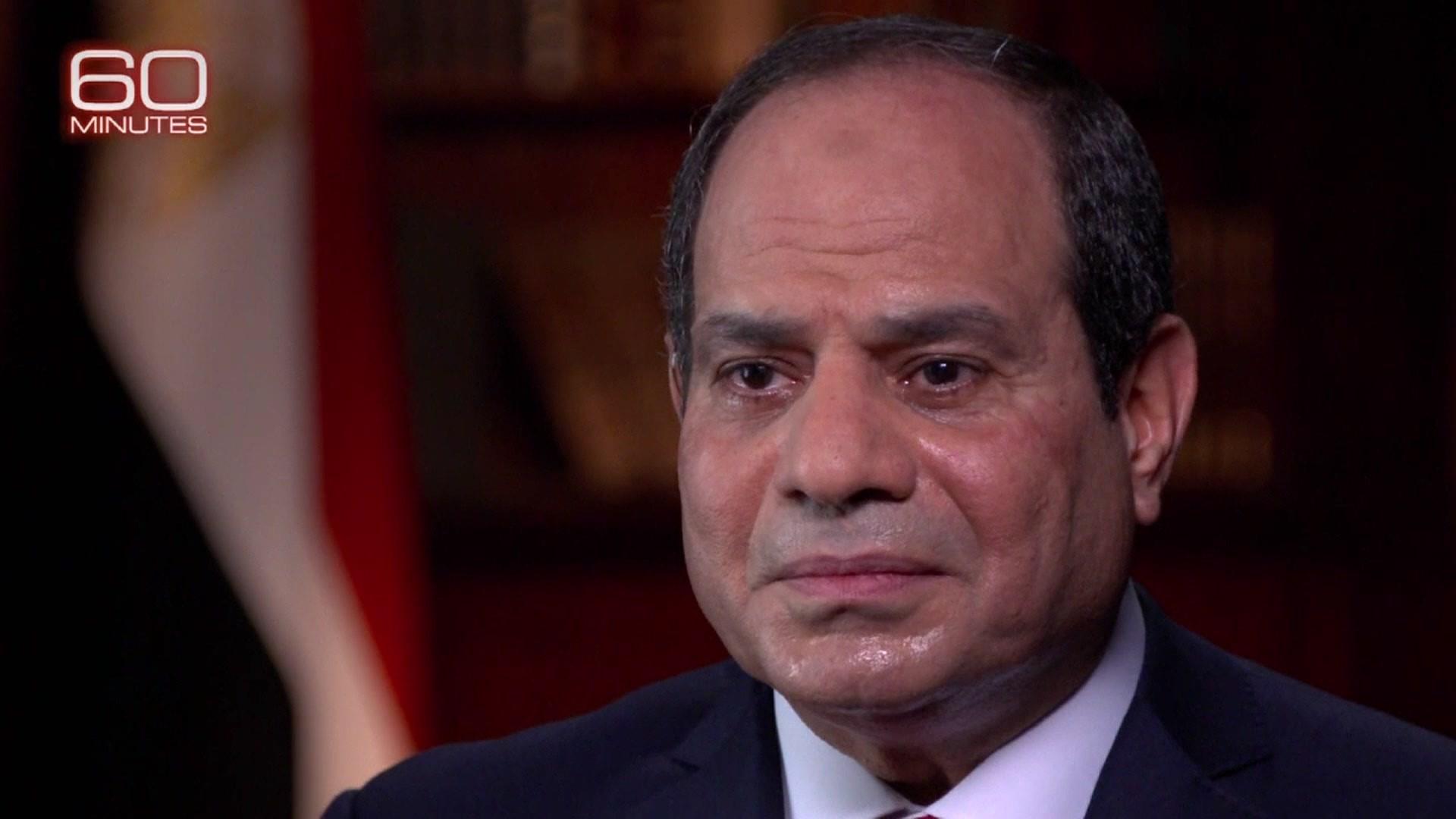

Such probationary measures have been used expansively against political activists who criticise President Abdul Fattah al-Sisi or played a role in the 2011 uprising which led to former president Hosni Mubarak's overthrow.

The aim, rights groups suggest, is to crush dissent and make the life of Mr Sisi's opponents harder. A set of laws, including the notorious protest law, make it almost impossible to publicly protest without taking potentially life-threatening risks.

The only way to demonstrate against the government in Egypt nowadays is through Facebook posts or Twitter hashtags.

Egyptian prosecutors and judges frequently issue conditional release orders and verdicts that incorporate non-custodial measures like probation, in addition to time in detention.

In September last year, 215 defendants - among them a well-known photojournalist known as Shawkan - were sentenced to five years in prison and a five-year probation period.

Shawkan was released in March but, like Samhi and Rami, he has to check in to a police station every night for the next five years.

'Wooden kiosk'

One man who has spoken up against the procedure is Alaa Abdel Fattah.

The blogger and software engineer rose to prominence during the 2011 uprising, and has spent five years in jail for organising an illegal protest.

He was released last month, but as part of his sentence, he must spend five years on probation at Cairo's Dokki police station.

Alaa Abdel Fattah has voiced his frustrations online about about the restrictions political prisoners face in Egypt

He sparked an online campaign on his first day in the system, when he posted on Facebook "unfortunately, I'm not free yet".

Using the hashtag #Half_freedom, he has been raising awareness about his probation conditions.

His family says he is being locked up in a wooden kiosk inside a police station with no access to his phone or laptop.

Alaa was reportedly threatened with more jail time unless he stopped talking - but so far he has refused to remain quiet.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Prosecutors sometimes order probation as a condition for releasing individuals before their trial - though they have the right to terminate this and take the defendant back into custody if the conditions are violated. The law does not specify what might amount to such violations.

"Police probation is used as a tactic to silence dissidents and muzzle opposition voices," Hussein Baioumi, Egypt researcher at Amnesty International told the BBC.

He suggested that the system of probation, which has been in force since 1945, was another form of "arbitrary detention practised by the Egyptian authorities against many peaceful activists for no reason except for expressing their opinion".

- Published6 May 2019

- Published4 March 2019

- Published4 January 2019

- Published5 October 2015