Iran nuclear deal: Why do the limits on uranium enrichment matter?

- Published

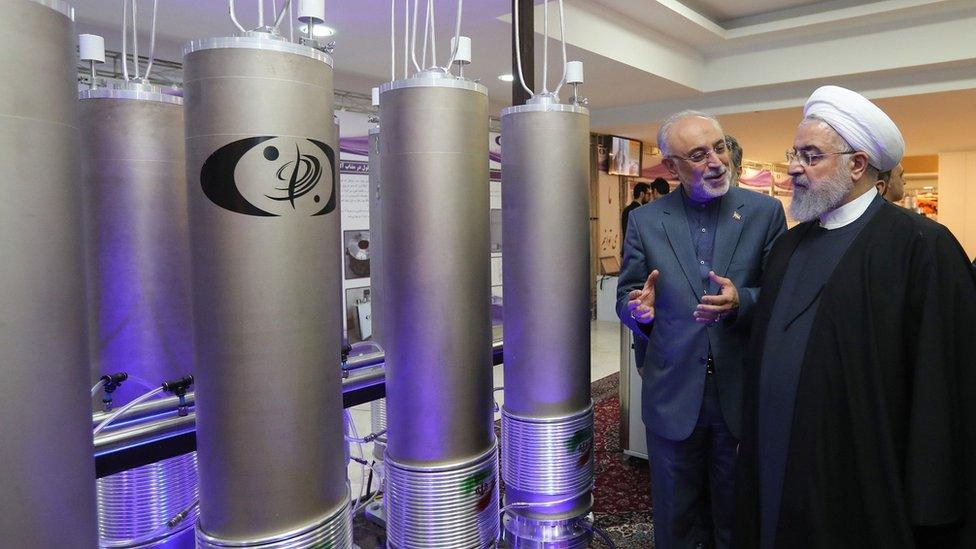

President Hassan Rouhani (R) says Iran is retaliating against US sanctions

The crisis over Iran's nuclear activities has escalated since the US under Donald Trump pulled out of an international agreement aimed at preventing Iran from developing nuclear weapons - something it says it does not seek.

One of the key points of dispute concerns uranium enrichment carried out by Iran as part of its nuclear programme. Here's why.

What is enriched uranium?

Uranium is an element which occurs naturally. It can have nuclear-related uses once it has been refined, or enriched. This is achieved by increasing the content of its most fissile isotopes, U-235, through the use of centrifuges - machines which spin at supersonic speeds.

Low-enriched uranium, which typically has a 3-5% concentration of U-235, can be used to produce fuel for commercial nuclear power plants.

Highly enriched uranium has a purity of 20% or more and is used in research reactors. Weapons-grade uranium is 90% enriched or more.

Iran's low-enriched uranium stockpile was limited to 300kg for 15 years under the nuclear deal

Under its 2015 nuclear deal with six world powers - China, France, Germany, Russia, the US and the UK - Iran was only permitted to enrich uranium up to 3.67% purity.

It also agreed to hold no more than 300kg (660lbs) of low-enriched uranium; to operate no more than 5,060 of its oldest and least efficient IR-1 centrifuges; and to cease enrichment at the underground Fordo facility.

How has Iran gone against the deal?

Under the deal, Iran capped its nuclear activities in return for a lifting of sanctions. Donald Trump reimposed US sanctions in November 2018, and since July 2019 Iran has increasingly breached the pact's restrictions. It has, among other things:

Exceeded the limit on its stockpile of low-enriched uranium

Resumed enrichment activity at Fordo

Begun using more centrifuges, and of a more advanced type, than it is allowed

Resumed enriching uranium to 20% purity and then started to produce smaller quantities of 60%-enriched uranium as well - a significantly higher level of refinement than it had reached before

Iran has continued to allow the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) to monitor its nuclear programme and says the steps are easily reversible.

Why do Iran's actions matter?

The country insists its nuclear programme is entirely peaceful. However, experts have warned that the breaches have theoretically reduced the time it would take Iran to acquire enough fissile material for one bomb. Even before Iran began enriching to 60% purity this April, they said the so-called "breakout time" had been shortened from about one year to three months, external.

Iran's nuclear programme: What's been happening at its key nuclear sites?

The IR-6 centrifuges being installed at Natanz are seven to eight times more efficient than the IR-1 machines Iran is allowed under the nuclear deal.

Enriching uranium to 20% purity and beyond also increases the potential for it being used for military purposes because the effort required to refine it to this point from its natural state is 90% of the total effort needed to get it to weapons grade.

The US-based Arms Control Association (ACA) said that once Iran had accumulated 170kg of 20%-enriched uranium, it would be able produce one bomb's worth, or 25kg, of uranium enriched to weapons-grade in less than two months.

Iran had about 17kg of uranium enriched to 20% purity as of mid-February and it has said it plans to produce 120kg in total during 2021. It is also currently producing nine grams per hour of 60%-enriched uranium.

The ACA said that while the break-out time could be extended if Iran reversed its actions, the knowledge Iran had gained by operating advanced centrifuges could not be undone.

Why did Iran stop complying?

It has said it is retaliating for the crippling US economic sanctions and other penalties that were reinstated in 2018.

Mr Trump called the agreement "defective at its core" and pursued a "maximum pressure" campaign to compel Iran to negotiate a replacement.

Iran's oil exports - the government's principal source of revenue - were hit by the reinstated US sanctions

Iran's leaders refused to do so and argued that the deal allowed one party to "cease performing its commitments... in whole or in part" in the event of "significant non-performance" by others. But France, Germany and the UK did not accept Iran's assertion.

Their hopes to save the deal from collapse were raised significantly when Mr Trump was succeeded as president by Joe Biden, who wants the US to rejoin it. But just before he took office this January, Iran ramped up its uranium enrichment in response to the killing in November of its top nuclear scientist Mohsen Fakhrizadeh, which it blamed on Israel.

Iranian nuclear scientist Mohsen Fakhrizadeh was killed in an ambush near Tehran

Iran again stepped up its enrichment - to 60% - this month in retaliation for a suspected Israeli sabotage attack at Natanz.

Israel, which sees Iran's nuclear programme as a potential existential threat and opposes international efforts to revive the nuclear deal, has neither confirmed nor denied involvement in either incident.

Does Iran want a nuclear bomb?

Iran insists it has never sought to develop such a weapon.

The international community does not believe that, pointing to evidence collected by the IAEA suggesting that until 2003 Iran conducted "a range of activities relevant to the development of a nuclear explosive device". Some of those activities continued until 2009, according to the IAEA.

In 2018, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said that secret Iranian documents obtained by his country showed Iran had surreptitiously continued nuclear weapons work beyond 2015, external. Iran has dismissed this as a fabrication.

Mr Netanyahu also said Israel had identified a "secret atomic warehouse" in a district of Tehran, believed to be where IAEA inspectors subsequently detected the presence of uranium particles of man-made origin. The IAEA has said Iran has not provided a credible explanation, external. Iran has said it has nothing to hide.

Despite such evidence, US intelligence agencies say Iran "is not currently undertaking the key nuclear weapons-development activities that we judge would be necessary to produce a nuclear device", external.