The Kurdish massacre survivor's 'mission from God'

- Published

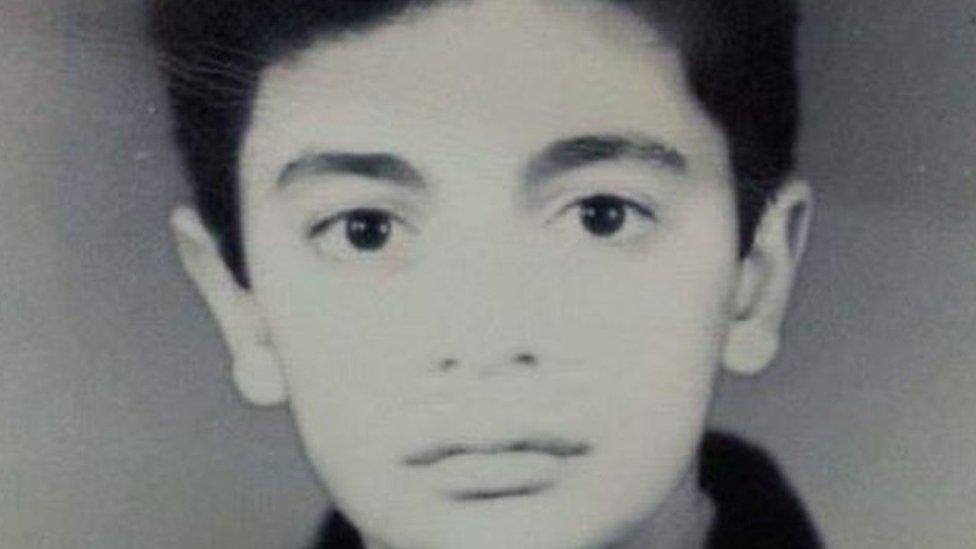

Taimour Abdulla Ahmed was the only person to survive the 1988 massacre

"I saw my mum getting killed in front of my eyes. I couldn't protect her. After that I saw two of my sisters getting killed."

Taimour Abdulla Ahmed is thinking back to the evening in May 1988 when, as a 12 year old, he and dozens of other children and women were forced into a desert pit and Iraqi soldiers opened fire on them.

Their crime - they were Kurds in Saddam Hussein's Iraq.

"My heart died with my mother and sisters in that grave.

"I get recurring flashbacks. I think about it when I go to sleep," says Ahmed, now 43, who remembers in graphic detail how the bullets killed his mother and two of his sisters.

He believes his other sister was shot dead in a neighbouring pit.

Ahmed is now seeking justice for the dead.

The possessions of some of those killed still lie in the ground

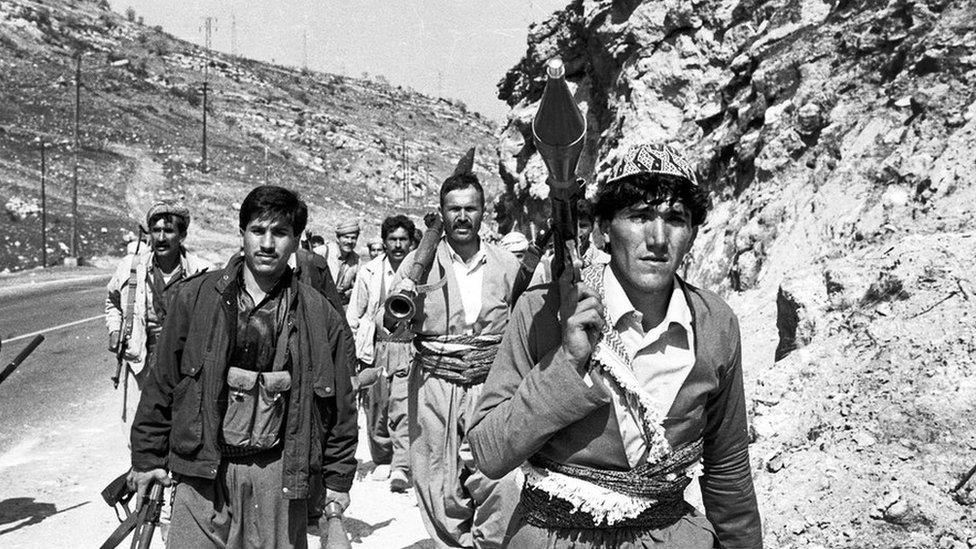

The killings were part of a campaign of collective punishment known as "Anfal" by the Iraqi government against the Kurdish people in the north. The authorities claimed they were quelling a rebellion after some Kurds sided with the enemy during the 1980 to 1988 Iran-Iraq war.

Human Rights Watch says up to 100,000 mostly civilians died in systematic ethnic cleansing, which involved the use of chemical weapons. Kurdish sources put that figure at more than 180,000.

At the time, Ahmed, his parents and sisters were living in Kulajo, a remote village of some 110 people, who were all part of the same extended family.

"It was difficult to find our village," Ahmed tells the BBC. But he says Kurds who were collaborating with Hussein's regime directed Iraqi forces there in April 1988.

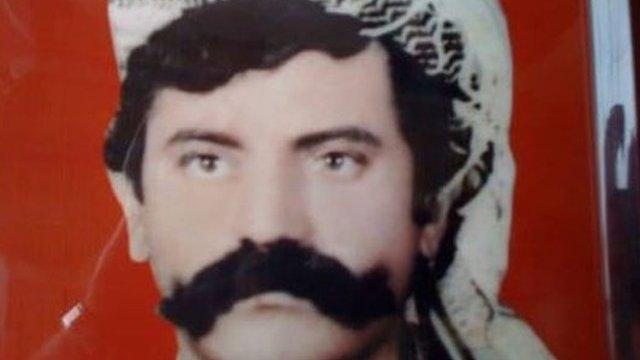

The villagers were rounded up and taken to a military camp where the men were separated from the women and children. That was the last Ahmed saw of his father.

Ahmed's father, Abdulla Ahmed, worked in agriculture like most of his fellow villagers

A month later Ahmed and the others were put into trucks and driven much further south.

"When the doors were opened I saw three pits next to each other. I saw two Iraqi soldiers armed with AK47 rifles."

The women and children - some of them babies in their mothers' arms - were forced out of the trucks and into the pits.

"All of a sudden the soldiers started firing at us."

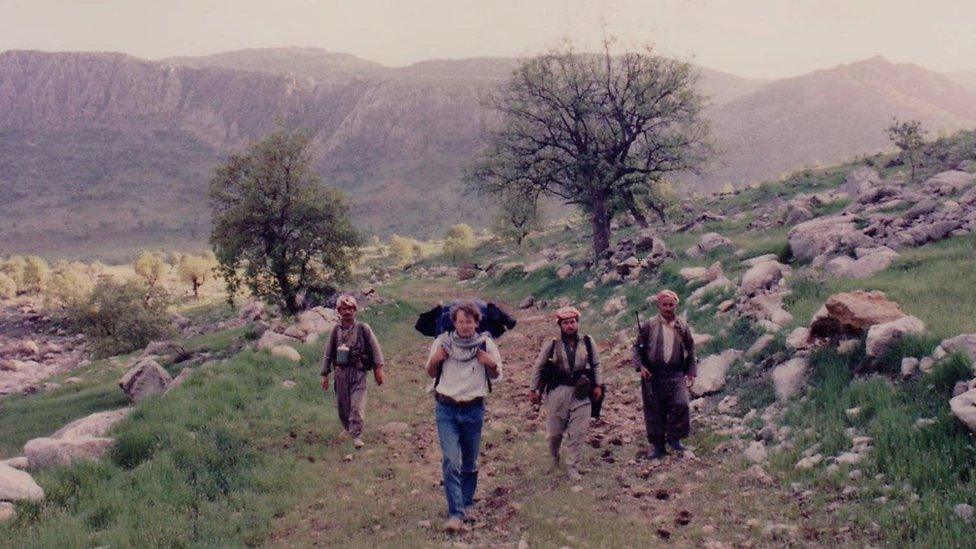

Ahmed's wounds were treated by traditional Bedouin healers

A bullet hit him in his left arm. "Bullets were fired next to my head, shoulders and legs. The entire ground was shaking. The whole place was full of blood. I got another two shots in my back. I was waiting for my death," he says.

He miraculously survived and played dead until the soldiers left. He then managed to get out from among the bodies and escape into the night.

He eventually came to the tent of a Bedouin family who looked after him. He stayed with them for three years until he made contact with one of his few surviving relatives and moved back to the north, where he still had to hide from the authorities.

In 1996 he was granted asylum in the US where he now lives.

Ahmed (L) says a Bedouin family risked their lives by looking after him

In 2009, after the toppling of Saddam Hussein, Ahmed returned to Iraq and found the massacre site.

"When I saw the graves I was shaking. I was crying," he says.

"I contacted the Iraqi government and told them that I needed to be informed about any decision regarding the graves."

But in June this year they started digging them up without notifying him. They plan to rebury the bodies in the Kurdish region.

When Ahmed heard from friends about what was happening he flew over from the US.

More than 170 bodies have already been recovered from the site, but Ahmed says the people carrying out the exhumations have left bones and possessions in the ground.

Mass graves in Iraq contain the remains of many Kurds executed by the Saddam Hussein regime

He is now involved in a stand off with the authorities and has taken legal action to prevent them from digging up the grave which he believes contains the bodies of his mother and two sisters.

He says only when they agree to do the work properly and "respectfully" and meet other demands, such as putting those responsible for the massacre on trial, should the exhumations continue.

He also wants to bring the massacre to the world's attention. "I want the cameras to zoom in on the bodies of innocent children clutching their mothers just before being shot," he says.

"I don't even have a picture of my mother and sisters. I want to take a picture with their remains," he adds.

Ahmed runs a vehicle parts business in the US

Iraqi officials say it is up to the Kurdish authorities to contact the relatives of the victims.

Fawd Osman Taha, a spokesman for the Kurdistan Regional Government, says they have to examine the remains and find signs of identification before contacting relatives.

"We gather evidence and send it to the special court responsible for prosecuting those who are guilty," adds Mr Taha.

Ahmed plans to stay near the site until his demands are met.

"I feel God wanted me to survive for a reason. God gave me a big mission and the mission is to talk about those innocent people who can no longer talk," he says.

- Published30 May 2016

- Published7 April 2016

- Published26 September 2015

- Published31 October 2017

- Published15 October 2019